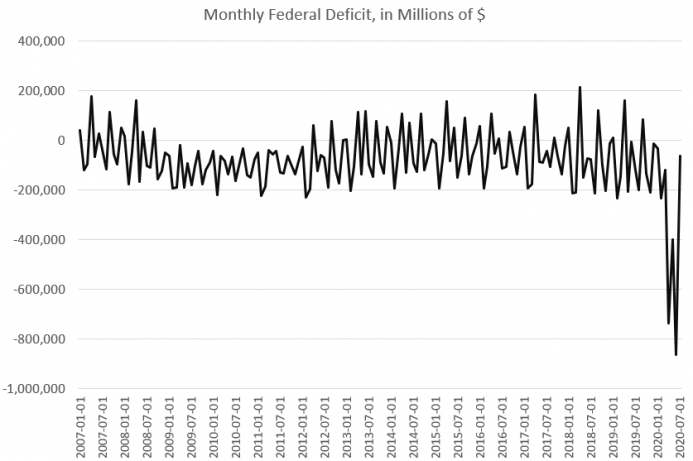

| The deficit narrowed during July after months of record shortfalls in federal tax revenues. During April, May, and June of this year deficits surges to unprecedented highs as economic activity dried up, workers were furloughed and laid off, and tax payments were deferred.

Nevertheless, according to the Treasury Department’s latest report on tax receipts and federal outlays, the gap between tax receipts and federal spending narrowed sizably during July. Although outlays increased to $626 billion during July (a 68 percent increase over July 2019), tax receipts surged to over $563 billion. During recent months, tax receipts have been anemic at best, with totals ranging from $173 billion to $249 billion since March 2020. July’s surge in revenue, however, does not indicate an improvement in the economy. Normally, tax receipts peak in April, but due to the covid-19 panic this year, tax deadlines were deferred, and those deferred receipts began to show up in Treasury data in July. |

Monthly Federal Deficit, Jan 2007 - Jul 2020 |

Expect More Huge Growth in DeficitsJuly’s receipt totals reflect previous economic activity from before the mandated lockdowns and declines in economic activity due to “social distancing.” In other words, it is likely that receipts will worsen significantly as we approach the end of the fiscal year, which ends on September 30. If so, we can expect the federal deficit to grow even more, bringing it to a new all-time high for the 2020 fiscal year. |

Fiscal Year Deficits, 2008 - 2020 |

Indeed, for this fiscal year through July, the federal deficit increased by more than 200 percent from 2019, rising to $2.8 trillion. For the same period of 2019 (October through July), the deficit was $866 billion. The last time the deficit even came close was when it topped $1.2 trillion for the same period of the 2009 fiscal year.

Trillions in New Borrowing

Poised to add more than $3 trillion to the national debt in 2020, the US is borrowing more than ever, and committing to ever larger dollar amounts that must be paid on the approximately $25 trillion debt.

So what kinds of debt payments are we looking at? Even before the covid-19 crisis hit, the Congressional Budget Office estimated that the US would pay more than $400 billion in 2020 (compared to approximately $650 billion for the defense budget). Except now the US is paying around $2 trillion more than was expected under last year’s estimates.

Moreover, the US is unlikely to be churning out any big surpluses any time soon. It’s a safe bet that deficits will continue to mount, and with them will come more interest payments on the debt.

“Deficits Don’t Matter”

Most Americans don’t seem particularly concerned about this.

A recent survey from the Pew Research Center suggests fewer than half of Americans rate the federal deficit as “a very big problem.” And why should they? Experience suggests that deficits—to use the words of former vice president Dick Cheney—“don’t matter.” After all, in recent years the Trump administration has racked up ever larger deficits, exceeding even $1 trillion in 2019, and it’s unlikely that many Americans see any connection between deficits and economic malaise.

The problem of massive amounts of deficit spending is more subtle than that.

In some cases problems only become obvious when interest payments on the debt grow considerably and begin to eat up the rest of the budget.

For now, it may be that the Treasury is “only” paying around $400 billion. But this is largely because the US pays such a low interest rate on the debt. Indeed, the interest rates on US debt are at historic lows, with the thirty-year bond at under 1.5 percent and shorter-term bonds at even lower rates.

There are unusually low rates, and even the Congressional Budget Office expects interest rates to increase considerably in coming years.

And what if interest rates increase to even 3 percent—which would still be a very low rate historically? If that were to happen, total debt service paid on the debt could surge to a trillion dollars or more. That’s an amount similar to the total paid out each year in Social Security right now. If that were to happen, Congress would have to find that money somewhere. To pay the interest, they’d have to cut funds from Social Security, defense, infrastructure spending, Medicare, or somewhere else.

As government checks got smaller, the public would finally start to understand the problem with deficits.

Turning Debt into Price Inflation

Moreover, the more the US has to borrow money, the more it floods the marketplace with US bonds, which would tend to push up the interest rate paid. After all, if a government’s going to be cranking out bonds seemingly without end, it will have to pay out more interest in order to convince investors to keep buying the bonds.

But there’s one big reason that even now, as the US adds another $3 trillion to the deficit overnight, interest rates aren’t going up.

That reason is the US’s central bank, the Federal Reserve. Rather than face the music of paying more interest at higher rates—and cutting federal spending to do so—the central bank is helping keep interest rates low.

The Fed does this by buying up new US debt in the open market. This helps keep demand for US debt instruments high, keeping interest rates low.

In part, this is why the Fed’s balance sheet now tops $7 trillion. The Fed has been buying up the US governments debts, among other assets, to so as keep interest rates low.

Of course, this doesn’t mean the problem is solved. The central bank generally makes these purchases with newly created money. That means the money supply grows, with resulting price inflation in both assets and consumer goods, all else being equal.

In other words, the downside of enormous and growing deficits is in a place many people wouldn’t think to look: in surging home prices, in rising food prices, and in a generally rising cost of living.

Making Income Inequality Worse

None of this is a particularly big problem for people who are already well-off or wealthy. In fact, for those who work in the financial sector it’s a windfall. But for people outside the financial sector, such as young couples looking to become first-time home buyers or single parents trying to make ends meet, things are less wonderful; this relentless inflation can be a big problem indeed.

Politically, however, this scheme can be kept up for as long as the US dollar continues to be the world’s reserve currency. When the dollar no longer has this advantage, the US will finally face a sovereign debt crisis.

But some observers apparently think this can still be avoided. A recent quotation in The Hill shows the sorts of naïveté that still pervade among observers of American politics:

“We have borrowed $2.8 trillion this year so far — triple what we borrowed last year,” said Maya MacGuineas, the president of the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget.

“…it will need to be followed by measures to bring the debt back down once the economy has recovered,” she added.

Until the US really faces a global move to dump the dollar as the reserve currency, or until interest rates in the US really start to climb, there will be no “measures to bring the debt back down.” We’re in a terminal debt spiral. The only question is how long it will last until the patient succumbs.

Full story here Are you the author? Previous post See more for Next post

Tags: Featured,newsletter