|

The NBER has made its formal declaration. Surprising no one, as usual this group of mainstream academic Economists wishes to tell us what we already know. At least this time their determination of recession is noticeably closer to the beginning of the actual event. The Great “Recession”, you might recall, wasn’t even classified as an “official” contraction until December 2008 – a full year after the NBER figured the thing had begun. Rather than becoming much better at spotting changes in the business cycle, whatever we all end up calling this one there’s no debating that something big happened in March 2020. If there remains any uncertainty, it pertains as to whether that was the actual start or if perhaps the thing had been underway before then. GFC2 is obvious, the downturn from Euro$ #4 more arguable. For now, there’s no difficulty in spotting March 2020 and thereafter because it shows up clearly in every single data stream. Well, almost every data series. |

US Trade in Goods, SA 2014-2020 |

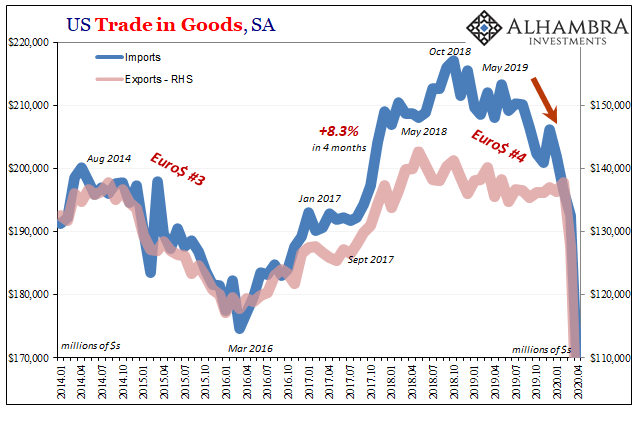

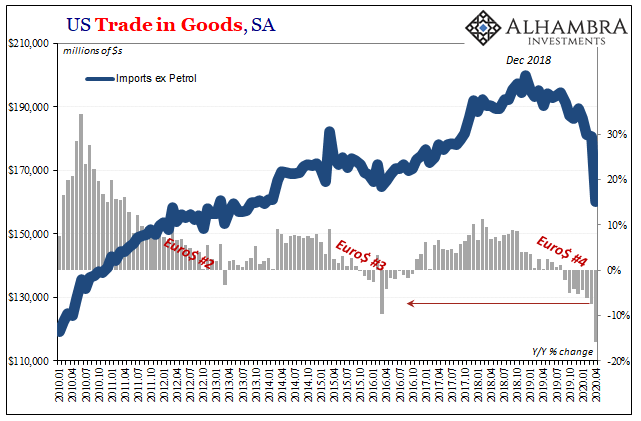

| Global trade figures from around the world demonstrate just what I mean. The US estimates are unequivocal about both March and before March. Imports, in particular, had shown that US demand for foreign goods had been falling since late 2018. Further, that decline had meaningfully accelerated around midyear last year (that whole “recession scare” thing with the yield curve). |

US Trade in Goods, SA 2010-2020 |

| What the NBER’s Business Cycle Dating Committee would say is that falling US imports doesn’t necessarily mean the US economy as a whole was in recession. And that’s absolutely true. In fact, there are times when certain sectors or segments might experience substantial weakness without it spilling over everywhere else.

Even so, you can’t (or shouldn’t) just ignore how that had happened and been well established so long before the idea of some novel coronavirus had been widely known. They list contributing factors on autopsies for a reason. Ultimately, though, it’s the “everywhere else” that the NBER uses to determine its recession dating. And what they say, for now, is nothing about before March. In other words, the decline in activity in and after March 2020 was so obvious that even the NBER has had to admit something big happened. It’s hard to ignore that massive drop you see above. However you might characterize the obvious declines previous to it, there’s absolutely no mistake about March and April. Again, you can see it in all the data – except for China’s trade numbers. |

China Exports, 2006-2020(see more posts on China Exports, ) |

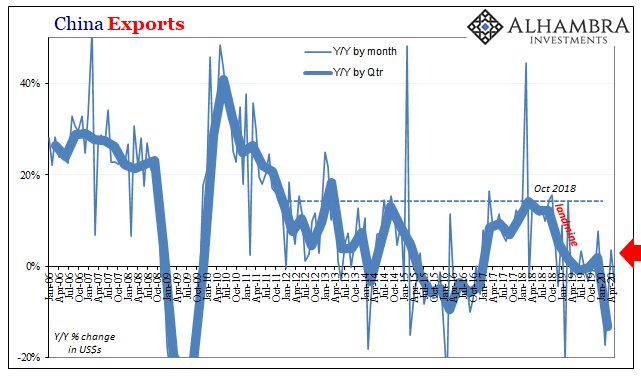

| Over the weekend, China’s General Administration of Customs reported May estimates for goods going in and coming out. Exports leaving the Chinese economy supposedly fell but only by about 3.3% year-over-year (following a 3.5% rise in April). Outside of the January-February period, there’s nothing to indicate much remains amiss (and the January-February estimates are notoriously noisy given their Golden Week calendar effects).

China’s major customers all report substantial economic interruptions all throughout, especially March and afterward, but from the Chinese perspective it’s as if there were only the two earliest months of disruption this year – when the major regions in China were themselves shutdown. |

China Exports, 2014-2020(see more posts on China Exports, ) |

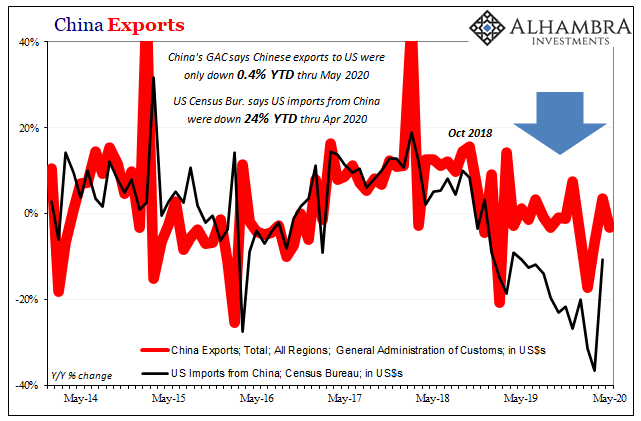

| Perhaps even more puzzling, China’s GAC puts Chinese exports to the US as down just 0.4%, in US$ terms, year-to-date in 2020 up to and including May. The US Census Bureau, on the other hand, says that US imports from China are off by nearly a quarter YTD through April.

In both series, there’s less of an imprint from COVID-19 than there has been from ongoing Euro$ #4. Global trade-wise, underlying weakness before is indistinguishable from the big things in March and afterward. |

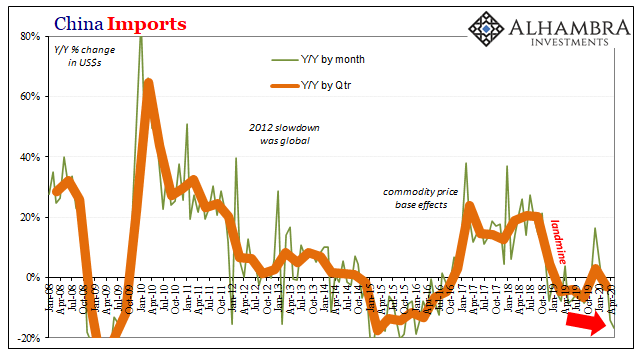

China Imports, 2008-2020(see more posts on China Imports, ) |

| In terms of Chinese imports, it’s nearly the opposite case from GAC’s export figures. Earlier in the year, imports were nothing out of the ordinary, and in fact were somewhat encouraging while the country wrestled with its initial outbreak; for January/February, down just 4% year-over-year followed by a 1% decline in March. Those accelerated to the downside, however, in April and May; -14.2% and now -16.7%, respectively.

China’s global customers supposedly buying up all of its goods at a near-uninterrupted pace during the same months when even the US NBER has figured out that’s probably not possible. And then, on the other side, China is presumably leading the world into its post-pandemic rebound and the level of imports accelerates to the downside. Some commentators are suggesting that commodity prices are to blame at least for the import numbers, the GFC2 collapse fomenting its pre-deflationary mess. While that’s true, it can’t all be commodity prices (valued in local CNY currency, total imports still fell by 12.7% year-over-year in May). But even if China’s import totals were entirely driven by the March through May price slump, where’s the COVID-19 impact otherwise? It’s curiously missing from the Chinese trade data in the opposite way that it is so obvious in the US (and everywhere else around the world). |

China PMI, 2010-2020(see more posts on China PMI, ) |

Like China’s strange PMI numbers of late, we’re led to believe that the Chinese economy was seriously disrupted in only just the one or two months early this year. And now, right back to where it left off like nothing happened.

The problem is, even if that was true, too, PMI’s like exports and imports wouldn’t just go right back to where they were. There’d have been a huge if temporary surge to make up for what was only supposed to have been lost time. If the economy had been disrupted in a truly non-economic fashion, there’d have been a significant and sharp catch-up at some point March to May.

What everyone wants to know is what comes next. There was a huge global downturn, one so big that even the NBER could spot it not long after it showed up. But what kind of rebound will follow from it?

Looking to China for help answering that question, as is natural, instead there are only more questions. According to Chinese figures, there isn’t going to be a “V” shaped recovery because the downside apparently wasn’t even long or lasting enough to merit anything other than business-as-usual.

And in itself that suggests everything else except business-as-usual.

Full story here Are you the author? Previous post See more for Next post

Tags: China,currencies,economy,exports,Federal Reserve/Monetary Policy,global trade,imports,Markets,newsletter