|

Japan’s central bank has little room for further easing despite a downbeat outlook. At its monetary policy meeting on 30 July, the Bank of Japan (BoJ) decided to keep its monetary policy unchanged, as expected. The decision came as the Japanese economy faces strong external headwinds and a downbeat outlook for domestic demand. However, we do not expect the BoJ to make any changes to its current monetary easing framework until H1 2020 as it has probably reached the limit of its easing capacity. Any possibly changes after that may involve just some minor tweaks in forward guidance and/or adjustment in certain parameters in its yield– curve control. In our view, the BoJ’s dilemma can to a large extent be attributed to the lack of coordination between monetary policies and fiscal policies. In the foreseeable future, however, we do not see any signs of aggressive fiscal stimulus, either. While the BoJ maintains the most aggressive monetary easing programme among major economies, Japan’s fiscal policy is at the opposite extreme. Excluding cyclical factors, Japan’s structural primary fiscal balance as a share of GDP improved by 4% between 2013 and 2018, meaning that fiscal policy was contractionary during this period. This policy stance is significantly tighter compared to the US, whose structural primary balance deteriorated by roughly 1% of GDP, and to Germany, whose primary balance remained virtually unchanged. |

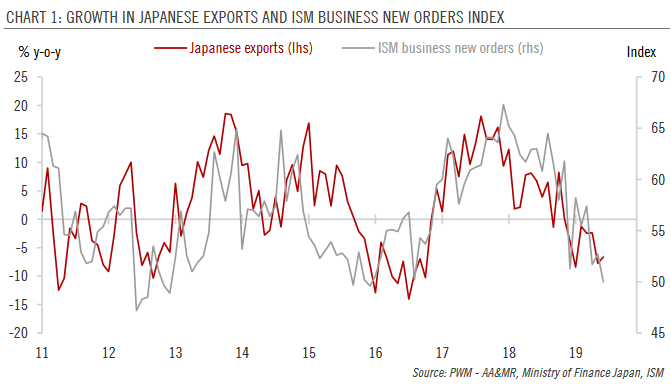

Growth in Japanese Exports and ISM Business New Orders Index, 2011-2019 |

After a significant pick-up in 2009, Japanese government expenditure has remained largely flat till now. In 2018 Japan’s total government expenditure was 2.5% lower than in 2013. Since Abe became the prime minister in 2013, growth in Japanese government expenditure has consistently stayed below nominal GDP growth, with the exception of just one year.

On the revenue front, Japan hiked its consumption tax from 5% to 8% in 2014 and is scheduled to hike it again by another two percentage points in October 2019. When Shinzo Abe first introduced the so-called Abenomics in December 2012, it was supposed to consist of ‘three arrows’ – monetary easing, fiscal stimulus and structural reforms. More than six years after the Abenomics made its debut, it would appear that monetary easing is the only arrow that has been fired with full strength, while fiscal stimulus is totally missing. To Abe’s credit, some structural reforms have been implemented with positive results (such as raising women’s labour participation rate and improvement in corporate governance). However, these reforms, combined with aggressive monetary easing, are apparently still not powerful enough to fully offset the negative demographic conditions faced by Japan and boost the country firmly out of its decade-long deflation mentality.

Will the mission be accomplished with some fiscal stimulus? We are not too sure. What is certain, though, is that without it, the likelihood is even slimmer. Moreover, we do not see any signs in the foreseeable future of aggressive fiscal stimulus in Japan. On the contrary, the next major event to watch out for is the consumption tax hike to be implemented in October… and the inevitable damage that it will cause for consumption.

Full story here Are you the author? Previous post See more for Next postTags: Bank of Japan,Macroview,newsletter