The first week of June features the Reserve Bank of Australia meeting, an ECB meeting, and the US employment data. The RBA is expected to deliver its first rate cut in three years. The market appears to have discounted not only a second cut in H2 but has priced nearly half of a third cut as well.

A soft inflation reading after the seasonal bump in April and disappointing survey data, with Brexit and trade tensions, means the ECB cannot be confident of a second-half recovery. Although officials have signaled that a tiered deposit rate was unlikely, many expect the details of the new targeted two-year loans to be generous, with the rate below the zero, where the refi rate is set.

While the US labor market remains robust, the April jobs gain of 263k likely overstates the case. Economists are mostly forecasting around 185k pace and the unemployment rate staying at the generation low 3.6%. A 0.3% rise in hourly earnings will keep the year-over-year rate at 3.2%. The average workweek slipped to 34.4 hours in April and may have recovered back to 34.5 hours. It has been alternating back and forth every month since last November.

Trade tensions are threatening to eclipse these macroeconomic events. Since the abrupt end of the US-China tariff truce, it has been the tension between the world’s two largest economies that dominated investors concerns and goes a long way toward explaining the increased volatility. VIX, for example, averaged a little less than 13% in April and nearly 16.6% in May.

Bond yields tumbled in May. The US 10-year Treasury yield finished May below the lower end of the Fed funds target range (2.25%-2.50%). The yield, after falling 33 bp in May, it is near 2.15%, the lowest in nearly two years. The two-year yield dipped below is near 1.90%. The 10-year German Bund yield was never lower, at little beyond minus 20 bp. The 10-year UK Gilt fell below 90 bp for the first time in three years. At nearly 70 bp, Spain’s 10-year yield is a record low. At 1.45%, Australia’ 10-year bond yield is five basis points through the cash rate. What illustrates this general point better than the record low 10-year Greek yield below 3.0%?

Previously, the consensus understanding was that central bank purchases of bonds drove down yields and encouraged the purchases of risky assets. When central banks finished their QE operations, interest rates would move higher, but they did not. There is a new consensus. Low yields reflect investor concerns about the economic outlook, which may seem kind of peculiar given that the world’s four largest economies (US, China, Japan, and Germany) exceeded forecasts for Q1 growth. Recent data have been disheartening. The Atlanta and NY Fed’s GDP trackers point to Q2 growth less than half the 3.1% revised pace of Q1. This data is before the impact of the new set of tariffs and counter-tariffs.

ChinaChina’s May PMI showed the manufacturing sector slipping back below the 50 boom/bust level after popping above in March and April. The forward-looking new orders and new export orders are below 50. While new non-manufacturing orders slowed, they remain above 50 (50.3), new export orders, ostensibly less impacted by the tariffs fell to 47.9 from 49.2. It is good that the consensus narrative is better aligned with the facts, but interest rates were trending lower in Q1 when economic activity was accelerating, while the tariff truce held, stocks rallied, and oil rose by more than 40%. There is a hypothesis that can better explain the decline in interest rates through the ups and downs of high-frequency economic data and tight credit spreads. It begins with treating the price of capital like we do the other factors of production and commodities. The price of capital may not simply be a divining rod to forecast the future, but it may also be subject to the laws of supply and demand. The low price of capital is a prima facie case for there being excess supply over demand. The secular stagnation hypothesis tends to see it as 1) a relatively new problem and 2) mostly as a function of modern industry not as capital intensive as the earlier phases of economic and technological development. Instead, the hypothesis here is that the supply of capital is in surplus as past ways of destroying it, such as wars and liquidation in a financial crisis, are less acceptable. Businesses used to be net borrowers of capital. No longer is this the case. Capital has also grabbed a bigger share of the social product (GDP) even though it has frequently found itself with nothing better to do with its capital than buy back shares and distribute directly to shareholders in the form of dividends. This surplus can be expressed as excess capacity in industry, which is where it is to be found in China, or siphoned away from productive assets into paper (financial) assets in the US and Europe. In this perspective, the Great Financial Crisis showed the limits of this strategy: the financial plumbing proved too unstable, destroying the financial system if it were not for a strange variant of lemon socialism, where governments bailed out banks and in some countries took equity stakes. One of the implications of this hypothesis is that interest rates will remain low for an extended period. They have remained low through the business cycle, which in the US, Europe, and Japan is at a mature phase. The idea that capital can be in surplus like anything else is not new. In the late-19th century, economists and policymakers in the US diagnosed their economic challenge (half of the last third of the 19th century was marred by panic, crisis, and depressions before the word “recession” was coined) as the “congestion of capital.” The answer they arrived at was the Open Door: A program of social spending, free-trade, and foreign direct investment (building production and distribution channels abroad). Free-trade and the globalization of production were embraced as a way to stabilize capitalism. It was stillborn as the US rejection of the League of Nations and the “Return to Normalcy” choked it off. It was resurrected after WWII and institutionalized in GATT (WTO), the IMF and the World Bank. |

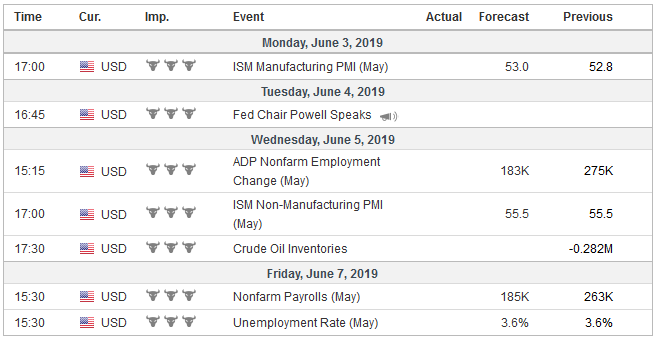

Economic Events: China, Week June 03 |

United StatesImagine what the world may look like in a few months on its current trajectory. The US has put 25% tariffs on all the goods from China and Mexico, the two largest sources of its imports. The average tariff in the US rises sharply from the current 1.7%. Because Japan and Europe are wary are voluntary export restrictions on autos, which the US appears to be demanding, and are in violation of the WTO, the US may carry through with its threat to levy a 25% tariff on all auto and parts imports. The US has made the claim that these imports are a threat to its national security. Japan and Europe are likely to respond with their own retaliatory measures. Other countries may be tempted to take preventative action to ensure that they are not flooded with goods themselves. The idea of negotiating China’s ascension in the WTO in 2001, when post-9/11 some commentators were talking about the end of globalization, was to manage its entry into the world economy. There was an appreciation for the enormous productive capacity it had by the sheer nature of its size, let alone the chronic misallocation of capital by bureaucrats. It was recognized at the time, even if forgotten subsequently, the re-emergence of China on the world economic stage was ultimately and profoundly deflationary. The rise of economic nationalism, this backlash against globalization, does not offer fresh answers to these two foundational questions: how to deal with the congestion of capital that has driven its price (yield) below zero in nominal terms and how to manage the integration of China’s vast capacity. There are around $10.5 trillion of negative yielding bonds, including 48% of European government bonds, according to data from Tradeweb. Let’s be frank, the scale of China would be disruptive even if it weren’t a command-driven economy. |

Economic Events: United States, Week June 03 |

In fact, even a free-trade agreement with the US does not offer protection from economic nationalism. Former seven-time president Porfirio Diaz once quipped that Mexico must be pitied because it is “so far from God and so close to the US.“ And so it is. The escalating tariff announced on Twitter undermines Mexico even if the tariff is rescinded in the near future. It tells the world, and in particular, possible foreign investors that a free-trade agreement does not prevent this type of action in the future. This access has been the key to Mexico’s development for the better part of the last 30 years.

It risks disrupting a tight schedule to get the new USMCA approved by the legislatures before the end of the summer due to the Canadian and US election considerations. It weakens the integration glue that has built a continental division of labor. It undermines the reason the US finally dropped the steel and aluminum tariffs on Canada and Mexico just after announcing the end of the tariff truce with China–protect the flanks, secure the supply lines. Canada, by implication, is less secure than it was a week ago. If the US can take action like this against Mexico, is any trading partner safe? Surely, this is a new factoid for negotiators from Europe and Japan that are negotiating an executive agreement that won’t require legislative ratification.

Investors were scared in Q4 18 as the conflict between the US and China intensified. The two presidents met in December 2018 and agreed to a truce. Equities rose, and capital flowed into risk assets, but bond markets remained strong. The truce ended on May 5, and it was the status quo ante. Stocks fell, and capital flowed out of risk assets. Bonds went from strength to strength. Economic nationalism threatens to weaken growth through raising taxes (on imports) and boosts problem created by maldistributed excess savings.

Sometimes it seems the markets are fishing for the official pain threshold. If the market pushes down interest rates far enough, can they get the Federal Reserve to cut interest rates? There is an equity equivalent: If the stock market falls far enough, will Trump and Xi call another truce or has some Rubicon been crossed, as we suggest? The surprise tariff move on Mexico caught everyone by surprise. Even if the move before the weekend was excessive, the low for interest rates and equities still likely lie ahead. The dollar may be particularly sensitive to any disappointment with the upcoming economic data, particularly the non-farm payrolls and auto sales.

Full story here Are you the author? Previous post See more for Next postTags: #USD,ECB,newsletter,Political Economy of Tomorrow,RBA,Surplus Capital,Trade