Last April, monetary officials in Japan were publicly contemplating ending asset purchases under QQE. This April, they are more quietly wondering what other financial assets they might have to buy just to keep it all going a little longer. I’d suggest something like the clouds passing over the islands or the ocean water surrounding them. Nobody would notice either way and it would be equally as effective.

Before the big stuff came in April and May (29), there were the first real hints of big global trouble at the end of January and into February 2018. Stocks, for instance, had been sailing along to new record highs (in the US, certainly) completely comforted by globally synchronized growth. Then, suddenly, apparently out of nowhere on January 29, 2018, liquidations struck.

What? How? Where?

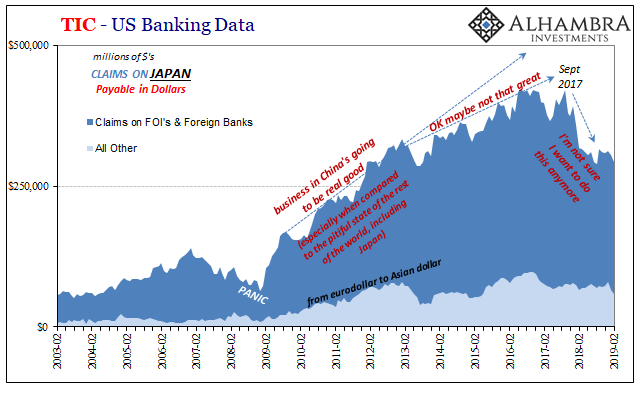

| A few months later, just as Kuroda was jawing positively for the Western media, TIC gave us a pretty good idea about the last one. The other two were therefore much easier to answer.

I wrote a little over a year ago:

|

TIC - US Banking Data 2003-2019 |

| Ever since the global eurodollar panic ten and eleven years ago, Tokyo has become a vital center for global “dollar” redistribution. Some people call it the yen carry trade, but in doing so they leave out several important distinctions: first and foremost, Japanese banks don’t need to borrow in yen, they’re already stuffed with “bank reserves.” They only need, therefore, two additional factors: someone to swap into US$’s with, before then “re-investing” them elsewhere (redistribution), and the willingness to do so.

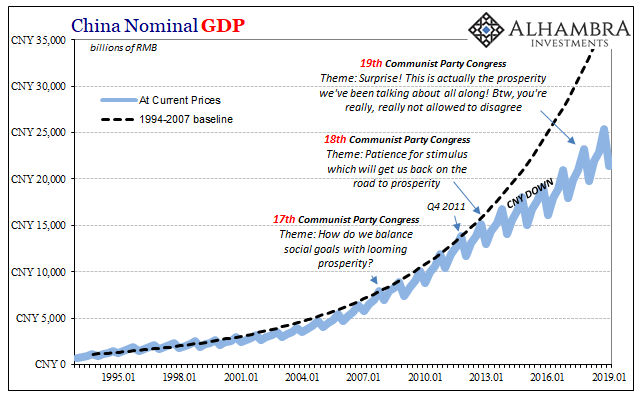

This doesn’t have to be an either/or situation. Tokyo’s dollar market participants might find FX funding a bit too expensive which then makes them less willing to engage in redistribution; which makes global dollars even more expensive, and so on. “Expensive” is a relative term, and one that includes two parts. Everyone forgets the second. If the opportunity is believed to be there, then costs could be exorbitant and the thing will still happen. Behind everything, it is perceptions of risk. Where Japanese banks seemed most interested as an endpoint for their eurodollar relocation business was, of course, China. They had tons and tons of yen, which the Chinese didn’t want, as well as inroads into the latter country’s vast interior. Those relationships along with local familiarity made Japan the perfect candidate to offer China what it did (desperately) need. But only until late 2017. While the rest of the world, at least in the mainstream, was lured by tales of globally synchronized growth, the Chinese were conducting their affairs very differently. Recovery, as they saw it, just wasn’t coming. They gave it a shot in 2016 and early 2017, but it wasn’t at all on the horizon. This view wasn’t some deep state Communist secret, either. At the 19th Communist Party Congress held, curiously, in October 2017 (the starting month for Japan’s re-redistribution eurodollar withdrawal), China’s leader Xi Jinping talked a lot about “rejuvenation.” Orwellian to the last, what Xi really meant was what I wrote at that time:

Put yourself in the shoes of Japan’s banks. You’ve taken on a lot of risk, and a lot more that’s maybe forever unappreciated (hey, that’s what you sign up for with Footnote Dollars). China’s supposed to lead everyone into recovery, you already sense that perhaps it’s not quite going that way, and then the Chinese leader in front of the world announces that the whole leadership is going to really start to re-orient itself for the downside.

|

PBOC Balance Sheet 2007-2019 |

| The crucial reverse for the Tokyo Eurodollar Express isn’t some huge mystery, nor is the timing. A booming China reduces risk. A “quality” growth China amplifies it. Opportunity is massively, and officially, downgraded. You wouldn’t have gotten the memo listening to Kuroda or Janet Yellen in the last months of her tenure contemplating her legacy.

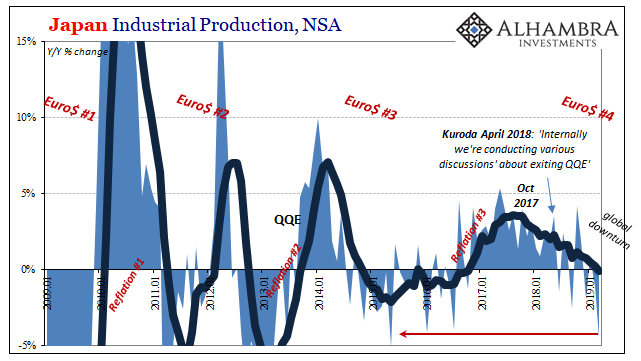

The insult to Japan is therefore Kuroda. All the while he, and his global central bank counterparts, were gloating, practically giddy about globally synchronized growth and what they saw as their own role in creating and nurturing it, the thing had already unraveled so much there was probably no turning back. Euro$ #4 was by last April inevitable. |

China Nominal GDP 1995-2019(see more posts on China Gross Domestic Product, ) |

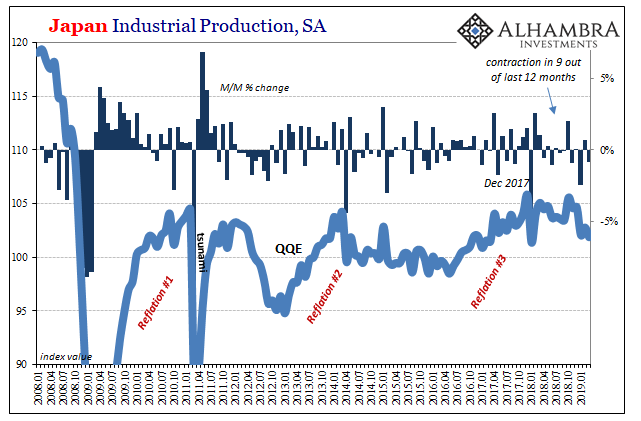

| What we are now seeing, including within Japan, is its rotten harvest. Japanese Industrial Production, maybe the best economic reflation/deflation indicator the last eleven years, continues to sink a quarter of the way through 2019. For those hoping green shoots or growth scare, in March 2019, according to figures released late last week, Japanese IP fell 4.6% year-over-year (not seasonally adjusted). It was the largest contraction since the middle of 2015 – the middle of Euro$ #3. |

Japan Industrial Production, NSA 2009-2019(see more posts on Japan Industrial Production, ) |

| The 6-month average for the noisy series is now negative for the first time since late 2016. Reflation #3 dead and buried. While Japan’s IP describes “what”, both the seasonally-adjusted and unadjusted series also take note of “when.” For the latter, it was October 2017; the former, just a couple months later.

The “how” is a global monetary system caught by what can seem like a Catch 22: it needs economic growth to create opportunity which requires monetary growth for that to happen. Else the inevitable eurodollar squeeze. These now dovish central bankers, more than those inside Japan, have become dovish based on what? Some minor and “unexpected” uncertainties in December 2018? Nope. They are already at least a year behind, and they have no idea what’s really behind it. This is green shoots. |

Japan Industrial Production, SA 2008-2019(see more posts on Japan Industrial Production, ) |

Tags: Bank of Japan,Bonds,China Gross Domestic Product,currencies,downturn,economy,EuroDollar,Federal Reserve/Monetary Policy,Haruhiko Kuroda,Japan,Japan Industrial Production,Markets,newsletter,QQE