More than two months after the general election, the Italian political impasse seems close to being broken, with the League and the Five Star Movement (M5S) likely to form a government. M5S and the League together have a majority in both the upper and lower houses. After several document leaks this week, a final common programme was published today. The document needs the approval of party members. The focus will shift to the designation of a prime minister (PM) and the distribution of key ministerial positions—a process in which the President of the Republic, Sergio Mattarella, will play a crucial role and likely act as a guarantor of stability. He will be able to use his power of veto if policies proposed by the alliance put Italy’s financial stability at risk or are against Italian agreements with Europe.

The new M5S-League coalition has pledged to implement a significant fiscal easing programme and to reverse some of the structural reforms undertaken by the previous governments. Such policies would likely put Italy on course for confrontation with Brussels over deficit reduction targets. A M5S-League government is also likely to take a hard line on other issues, including immigration and broader European policies.

Crucially, however, both parties have dropped their call for a referendum on Italy’s continued membership of the euro area, toning down their eurosceptic rhetoric considerably during the election campaign. As opposed to the previous draft published at the beginning of the week, the call to cancel part of the public debt or review calculation’s method has been removed from the programme of government document published on Thursday.

The most worrying point from a market perspective is the (vague) idea of funding part of the spending programme via “fiscal credit certificates”, or government IOUs. Details are scarce but the plan shares similarities with the ‘mini-BoTs’ proposal that has been floated in various forms in the past, fuelling concerns over the implementation of a parallel currency.

Italian government bonds (BTP) are likely to remain under pressure depending on the actual initiatives undertaken by the new government. A continuation of dialogue between Rome and Brussels will be needed for sovereign bond spreads to stabilise in the near term, let alone to tighten. Looking ahead, any significant deterioration in the economic and fiscal outlook would raise the risk of a rating downgrade.

On a brighter note, the difference between the situation today and the 2011 sovereign debt crisis, when markets questioned Italian debt sustainability, cannot be stressed often enough. Macro-financial fundamentals have nearly all improved since then. The main risk we see with a M5S-League government is that Italy’s growth potential fails to improve, leaving longterm challenges intact, if not worse, when the next economic downturn hits.

Is the modest cyclical recovery at risk?

The Italian economy has been experiencing a modest cyclical recovery since the end of 2016. A number of near-term vulnerabilities have faded. In particular, banks’ non-performing loans are declining and Italy is running a current account surplus. Leading indicators (for example, the latest PMI and Istat surveys) suggest that the recovery remains broadly on track. At this stage, we see no reason to change our annual real GDP forecast of 1.4% for Italy in 2018. Although downside risks have arguably increased since the start of the year, this is true for the whole region and not specifically for Italy.

What will happen to fiscal policy?

Both the M5S and the League have committed to a significant degree of fiscal easing through various measures. Based on the information that has filtered, the government agreement takes accounts of both parties’ most important policy pledges, including: the reversal of Mario Monti’s 2011 pension reform; a flat tax of 15% for corporates and 15-20% for households, and the simplification of the tax system; and a universal income of EUR780 per month. The policy measures included in the government agreement, if confirmed, would result in a significant increase in the fiscal deficit of the order of €109bn-€126bn, according to an estimate of the Osservatorio CPI. Needless to say, such proposals are unlikely to be welcome by the European Commission, even assuming some watering down.

Other measures include plans to tighten the ways in which lenders can recover amounts due from retail borrowers. On foreign policy, proposed measures include the lifting of sanctions on Russia, tougher immigration rules, and the renegotiation of Italy’s contribution to the EU budget.

Is Italy on course for collision with Brussels?

Italy is currently under the preventive wing of the EU’s Stability and Growth Pact. Some flexibility was granted to Italy due to refugee-related and security expenditure in 2016 and 2017, while adjustments were required to make the 2018 budget consistent with EU rules. The expansionary policies proposed by the alliance and the repeal or revision of some structural reforms are likely to raise tensions between Rome and Brussels. Thus, a long and difficult negotiating process will start, focusing on the incoming government’s fiscal policies and reform agenda (or lack thereof). The negotiations will culminate with the presentation of the 2019 budget in parliament (by end-September) and its submission to the European Commission (by mid-October). We would expect the negative noise around these negotiations to intensify, at least initially, given the previous antiEuropean rhetoric from M5S and the League (albeit somewhat cooled down of late). Brussels also has an incentive to play hardball with a eurosceptic government as long as market tensions remain contained.

Any attempt to introduce a flat tax and other fiscal easing measures as well as any move to reverse Mario Monti’s pension reform are likely to prove the most controversial initiatives the incoming government could undertake. Unwinding pension reform is likely to be especially problematic for the European Commission. Remember that the degree of flexibility that Brussels has shown regarding Italy’s budget has always been conditional on an ambitious reform agenda. On balance, we believe that there will be room for discussion and compromise, as long as the new Italian government plays by European rules. Either way, a reality check will come soon.

One issue in particular could help both parties to find a compromise. The new Italian government will likely seek a way to avoid the automatic VAT hike scheduled for 2019 that was included in the safeguard provisions drawn up with the European Commission during the sovereign crisis years. In return, European policymakers could ask for adjustments to other measures, including the incoming government’s plans for pensions and the labour market.

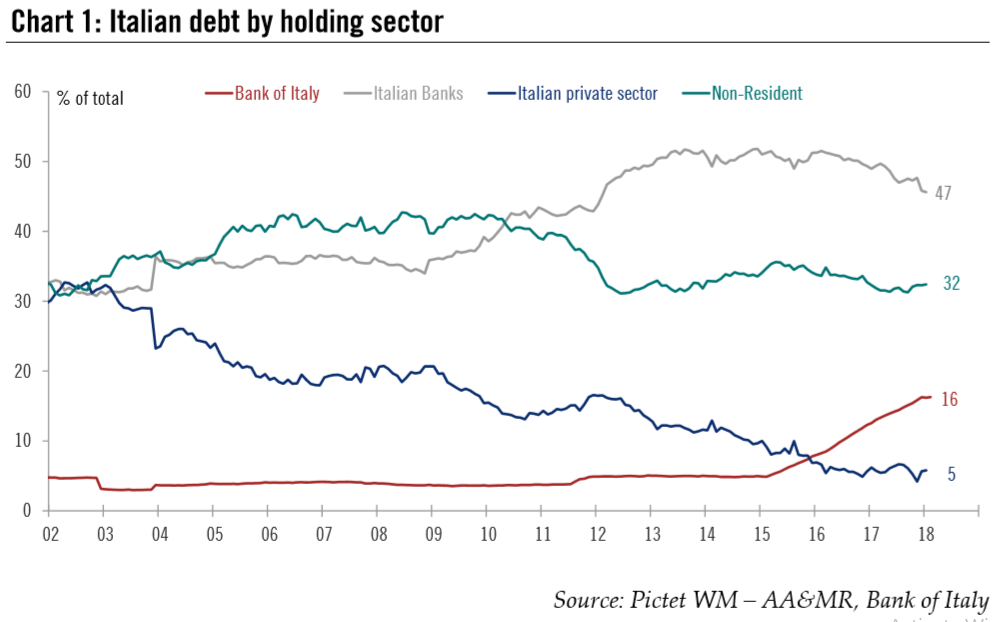

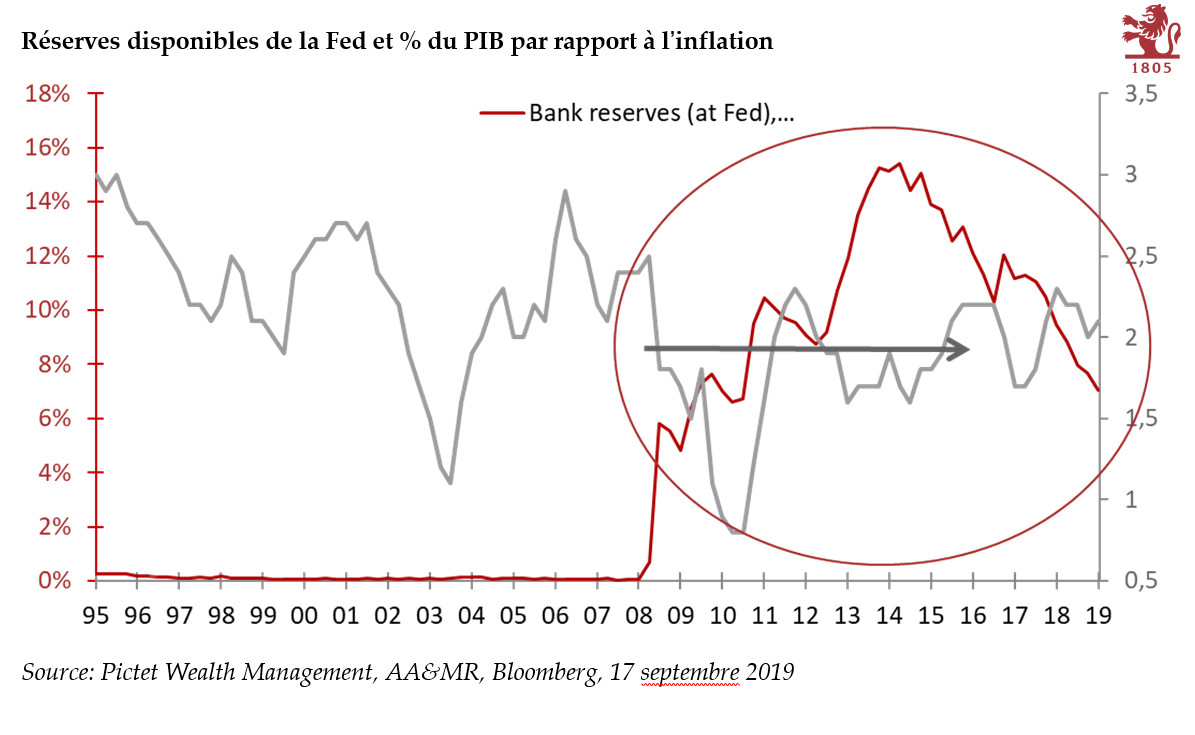

Are public finances threatened by a sudden rise in interest rates?We doubt it. As we have argued in the past, there are sufficient buffers against negative events. Macro fundamentals and public finances have improved significantly since 2011, when there was a question mark over Italian debt sustainability. The deficit reached 2.1% of GDP in 2017, well below the 3% target, and the country runs a considerable primary surplus of 1.5% of GDP. Italy’s external position has improved as well, with the country’s current account surplus rising to 2.8% of GDP last year. Importantly for debt sustainability, interest payments on the past stock of debt and the implied interest rate on debt (currently 2.8%) are at their lowest levels since the launch of the euro. In addition, Italy’s debt management office has taken advantage of low interest rates to raise the share of long-term fixed-rate bonds in its issuance. As a consequence, average debt maturity has been close to seven years for some time. Meanwhile, the share of public debt in the hands of foreign investors and Italian banks has decreased, to 32% and 47% respectively (see Chart 1), of which only a small fraction is held outside the EU. Therefore, the risk that a sudden negative event triggers systemic consequences looks much smaller than before. |

Italian Debt by Holding Sector, 2002 - 2018 |

Will the ECB have to adjust its exit strategy?

The short answer is no. The ECB should not, and in our view will not, deviate from its well-communicated normalisation path because of an unwelcome development in Italian politics, albeit one that was backed by more than 50% of voters. If anything, a fiscal stimulus and some rolling back of reforms could make the ECB marginally more hawkish.

This is only true within the terms of the ECB’s mandate, obviously. Were financial tensions to mount to the point where an unwarranted tightening of broader financial conditions were to challenge the adjustment in the path of inflation, then the situation would change. But the bar for a change in ECB policy is high, in our view, and the ECB will rightly want to avoid being perceived as increasing its support to a government going in the ‘wrong direction’ as regards fiscal policy and structural reforms.

What would be the impact of fiscal profligacy on bonds?

The new government has put at risk our central scenario of a slight widening of Italian spreads to 160 bp by year-end, with a higher risk of overshoot to 200 bp depending on the actual policy measures that will be implemented. Italy’s fiscal policy has been restrictive since 2011, leading to an improvement of its debt sustainability, as mentioned above. In our central scenario, we expect the new government to become more lavish in its spending plans, but also to keep negotiating with the European Commission.

A ratings downgrade would increase the pressure on BTPs. As a matter of fact, Italian debt is already considered to be of lower quality than Spanish debt, since the latter has been regularly upgraded in recent months (from lower-medium to upper-medium grade). This explains why the spread for Spanish government bonds over Bunds is much lower. Italy still benefits from investment-grade ratings from the four main rating agencies, but they have all warned that fiscal profligacy on the part of the new government could lead to a downgrade— although a lowering of two notches would be necessary for Italian government debt to decline from investment grade to high yield status. A downgrade is not part of our main scenario, but such threat could fuel further widening pressure on Italian spreads over the coming months.

Full story here Are you the author? Previous post See more for Next postTags: Macroview,newslettersent