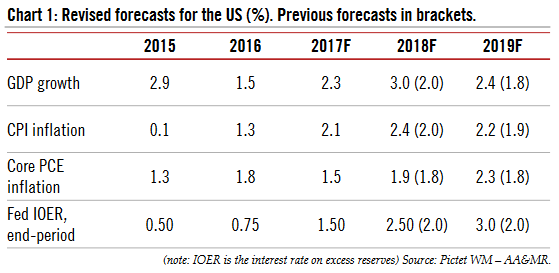

| December’s US tax cuts – which saw corporate taxation reduced particularly sharply – are being echoed in signs that ‘animal spirits’ are finally kicking in. Both set the stage, in our view, for higher US growth, in large part driven by greater investment. We therefore upgrade our 2018 US growth forecast from 2.0% to 3.0%. We forecast that real non-residential investment growth will accelerate to 7.0% in 2018, up from an estimated 4.6% in 2017. We expect 2019 GD P growth to come in at 2.4%, up from our previous forecast of 1.8%.

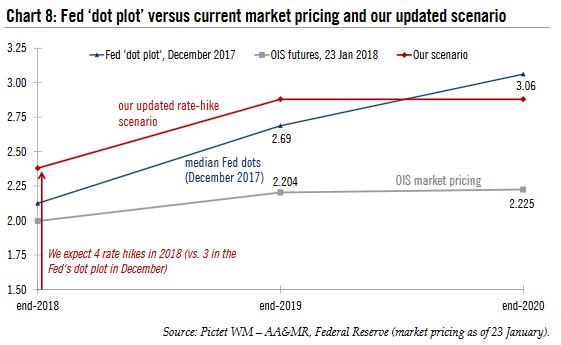

We are also raising our inflation forecasts, although we anticipate some inertia in core inflation this year as the higher wages we expect to see might take a few quarters to feed into prices. We expect core PCE inflation to move up from 1.5% on average in 2017 to 1.9% in 2018 and 2.3% in 2019. We expect the Federal Reserve to hikes rates four times this year rather than twice, as we previously expected. And we see two rate hikes in 2019 (versus none previously), with the Fed eventually pausing the rate-hiking cycle when rates are at 3.0%. The (real) theoretical neutral rate, now estimated to be in the vicinity of 0% according to the Laubach-Williams measure, could move up to 1% due to newly energised investment and higher productivity. In the shorter term, we think the Fed could raise its 2018 dot plot from three to four rate hikes at its March meeting, when it will very probably raise its own GDP growth forecast. The main risk to our macro forecast is a sudden return of inflation and a sharp rise in bond yields. We expect a gentle upward slope in wages and core inflation, but the risk to our view is that the Phillips curve (which links a strong labour market to inflation) reasserts itself more vigorously. This could unsettle Fed officials and lead to more aggressive tightening. More broadly, we think financial conditions hold the key to 2018–19 growth. |

Revised Forecast for the US, 2015 - 2018 |

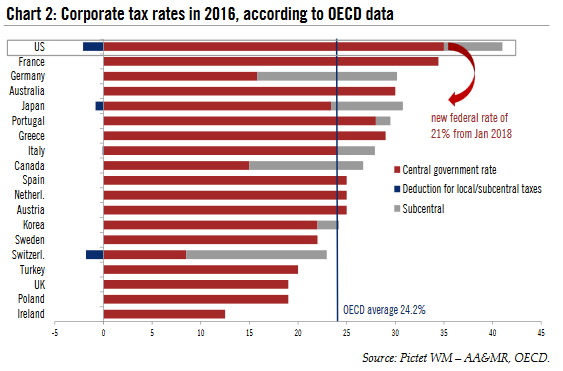

Tax cuts are mainly geared towards corporatesDespite the ongoing political tension in Congress and within both political camps – on display when the federal government partially shut down for three days in January – Congress still managed to pass a bold tax bill in December. The tax bill is geared in large part towards corporates, slashing the statutory corporate tax rate from 35% to 21%. The US government has stressed that this sharp cut brings the US rate closer to the OECD average of 24.2% (although in the US, one still has to add state tax to the federal rate). In other words, it is a big step forward for US competitiveness. There are other important tweaks too, particularly the full expensing of capital spending for tax reasons (versus half-expensing previously), which are a positive signal for investment. There are important changes – and this is where the real ‘reform’ lies – to how multinationals are taxed , with a move towards a territorial (rather than a worldwide) tax regime. The transition is helped by a one-off tax on previously untaxed assets held offshore (15.5% on cash and 8% on real assets). There are also new taxes including a “base erosion anti-abuse tax”, which is aimed at reducing offshore profit -shifting and aggressive tax planning. Pass-through entities’ taxation is also modified (20% deduction, phasing out at USD 315,000 for couples). Meanwhile, there are some curbs on tax loss carry forwards, and some limits to debt interest deduction for tax purposes. The changes to taxes on individuals are more modest. The top income tax rate falls from 39.6% (kicking in at USD 500,000 / year for a single filer) to 37.0% (kicking in at USD 418,000 / year). The standard deduction is doubled to USD 12,000 (single filer), while child tax credit is doubled to USD 2,000 (with a higher refundable portion). Other tweaks include a cap on all state and local tax deductions at USD 10,000 – which could prove painful in high-tax states such as New York and California – and a cap on the mortgage interest deduction (with a maximum mortgage limit of USD 750,000, down from USD 1,000,000 previously). The penalty for not having health insurance will be eliminated from 2019, while the estate tax (inheritance tax) threshold is almost doubled to USD 11.2 million. There are no changes to capital gains tax. |

Corporate Tax Rates in 2016 |

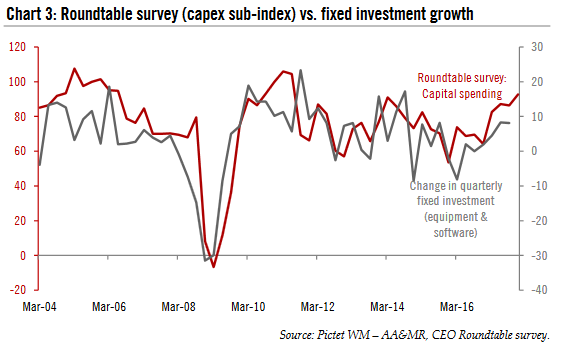

‘Animal spirits’ may finally kick inSince the tax cuts have been enacted, many corporations have come forward to announce increased investment plans, higher employee compensation and / or one-off bonuses. In fact, the extent and synchronicity of these announcements have come as a surprise to many – including us – and even to President Trump, who evoked a “big, beautiful waterfall” at his Davos speech on 26 January 2018. The website of the Business Roundtable, a forum of US CEOs, has reviewed many of these announcements: among the highlights are Wal-Mart’s increased starting wage (up from USD 10 to USD 11/hour) and a one-off bonus for employees of up to USD 1,000. Another example is AT&T offering USD 1,000 to its employees as a one-off bonus, while promising greater investment in the US. Apple went further, giving its employees a USD 2,500 bonus (in shares). It also promised to accelerate investment in the US (350bn over the next five years) as it ‘freed up’ the cash it has held offshore for tax purposes up to now, as have many other multinationals – particularly in the tech sector. These announcements have been highly visible in the media, and may incentivise other corporations to follow suit. While this is mostly anecdotal evidence of the power of the tax cuts, they come at a time of very high business and consumer sentiment, and hot on the heels of a particularly strong holiday shopping season. Business investment has been the missing link in the economic recovery, but there are signs that investment could now start surprising on the upside. Business surveys certainly point towards increased investment . A survey we monitor closely, the CEO Roundtable survey, saw its economic outlook sub-index rise to 96.8 in Q4 2017 – its highest level since Q1 2012. The latest survey was carried out in early December, just before the tax cuts were formally enacted, so the next quarterly reading could be even higher. It is also worth noting that the capex sub-index rose to 92.7, its highest level since Q2 2011. Increased confidence and signs of rising investment are also evident in other surveys such as the ISM manufacturing survey, the ‘new orders’ sub – component of which rose to 69.4 in December, its highest level since January 2004. Further evidence of additional investment lies in the stock market : brokers – themselves translating guidance from CEOs – have revised their capex projections for 2018 sharply upwards in recent weeks. Capex at S&P 500 companies is expected to rise by 5.5% in 2018, according to Facts et data (last September, it was only expected to increase by 2.6%). |

Roundtable Survey vs Fixed Investment Growth, march 2004 - 2016 |

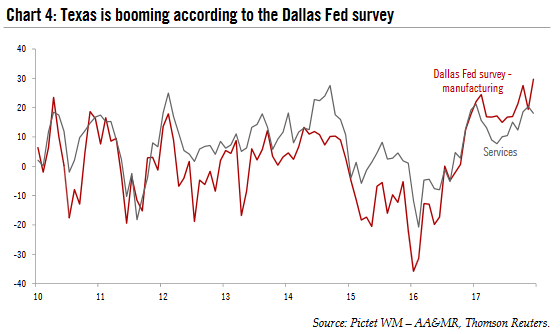

Strong domestic oil sector, solid global economyThe tax cuts come at a time when other drivers of growth in the US are in full force. Global growth is particularly supportive , leading to solid export demand. Export growth to emerging markets was particularly robust last year, and momentum remains strong. Exports to China were up 12.3% in the period January – November 2017 (in nominal terms) relative to the same period the previous year, while exports to South Korea rose by 15.2%, by 15.1% to Hong Kong and by 22.2% to Brazil. The ISM survey also showed that export orders remained strong at the end of 2017 : its new export orders sub-index rose to 58.5 in December. Meanwhile, the domestic energy sector is at full steam. Momentum is expected to continue as global oil prices creep up. In its January outlook, the International Energy Agency revised its 2018 US crude oil production forecasts up from 0.87mb/d to 1.10mb/d, stating that it saw a “return to the heady days of 2013–15”. As we have repeatedly highlighted in our publications, the epicentre of the recent oil boom is Texas (the second -biggest state in the US in GDP terms after California), a state that is crucial to the US economic outlook. It is worth noting that the December Dallas Fed manufacturing survey rose to its highest level since March 2006, echoing the broader ‘boom’ in the energy sector that is filtering through to the local economy and nationwide. |

Dallas Manufacturing FED Survey, 2010 -2018 |

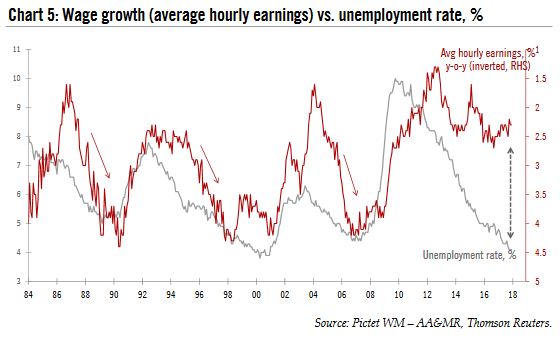

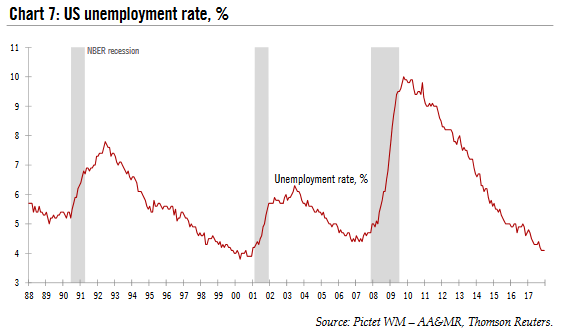

Our forecasts in detail: investment in the driving seatOur revised 2018 growth forecast of 3.0% is mostly based on an acceleration in non-residential investment: we expect it to grow by 7.0% this year, up from 4.7% in 2017 and – 0.6% in 2016. We think personal consumption growth will remain solid at 2.7%, in line with the growth rate in 2017. While we expect disposable incomes to creep up, we also see potential for inflation to rise somewhat as well, eating away at some of those gains. The saving rate is expected to stabilise at low levels after falling sharply in 2017 on the back of increased use of consumer credit. Meanwhile, we forecast that residential investment will rise from 1.7% last year to 3.0% in 2018, and that government spending will increase from a measly 0.1% in 2017 to 1.9% this year. In other words, both categories should play ‘supporting roles’ in our 2018 forecast. On a quarterly basis, we do not believe that Q1 growth will be as affected by winter seasonality as in previous years, despite the winter storms that hit the Northeast in early January. The sharp drag from trade and inventories in Q4 2017 should reverse in Q1, offering additional support. Our Q1 2018 forecast stands at 3.4% q-o-q SAAR (3.0% y-o-y), pretty much in line with recent business surveys and leading indicators. We expect average quarterly growth of 3.3% in H1 2018, and 2.9% in H2 2018. Risks to our forecast – ‘Phillips curve re-awakening?’The main risk to our solid growth forecast of 3.0% lies in disorderly Fed tightening and, more broadly, tighter financial conditions. A significant acceleration of inflation, particularly if price pressures started to be more responsive to the ongoing reduction in economic slack (our ‘Phillips curve reawakening’ alternative scenario) would increase the likelihood of just such a disorderly tightening. This comes at a time when the labour market is already tight, with the unemployment rate close to 4% (which is considered to be full employment). We think the Fed could be more sensitive to wage data than inflation itself as it still believes in a strong relationship between wage growth and price pressures, according to its classical economic view. |

Wage Growth vs Unemployment Rate, 1984 - 2018 |

| Still, there are a few mitigating factors. First, a sharp sell-off in the bond market would probably lead the Fed to slow or pause its tightening, as we saw after 2013’s ‘taper tantrum’. Second, we think the bar to raise rates more than four times a year is very high. Many Fed officials have highlighted that they could be open to a more permissive view of higher inflation (up to a certain point, of course) given how low inflation has been in recent years. While the possibility of moving from three to four rate hikes this year is relatively high in our view, it is much more difficult to see the Fed hike rates five or six times given the risk of sending a signal of a major shift in the Fed’s policy regime.

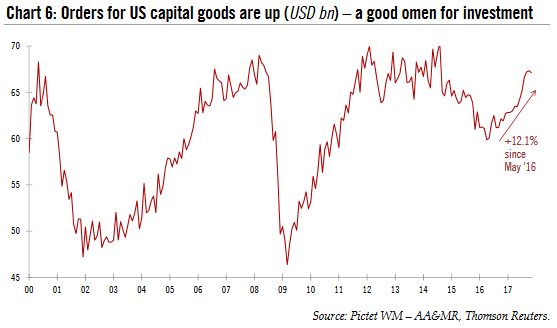

Another risk to our scenario is that investment fails to accelerate as we expect. Some observers have pointed out that the cost of capital has been low for several years due to very loose monetary conditions (low Fed and market interest rates), but this has not had the positive impact on corporate investment that policymakers had been expected. But now there are signs that animal spirits are kicking in. Stock markets are up strongly, business confidence is reaching new highs, and CEOs have started to be very vocal about stepping up investment. Meanwhile, tech investment remains front and centre as the economy continues to evolve, with robotisation, automatisation and digitisation top of the agenda in many sectors. If investment fails to accelerate, there is the related risk that productive capacity remains constant, increasing the danger of the economy ‘overheating’, possibly leading to recession. Our updated scenario is based on the continuation of the business cycle, even though we acknowledge that it is already long in the tooth by historical standards. The quality of investment, and of the growth rate of GDP , is critical. Another risk would be a sharp drop in global energy prices, leading to a rapid end to the domestic energy boom. This could potentially happen if global oil demand were to weaken unexpectedly, for instance in emerging markets, where the bulk of demand growth is expected to come from. Another danger is that OPEC fails to renew its commitment to cut production, especially in tandem with Russia, leading to new oil supply reaching the market. |

Orders for US Capital Goods, 2000 - 2018 |

| Over-production by US shale players is a further risk. That said, many oil players now seem to be in favour of more discipline in their capital spending, in part driven by new guidance from shareholders and bondholders warning against ‘growth at all cost’.

Finally, another major risk lies in uncertain politics. There is a strong focus on trade policy at the moment, with tensions between the US and its NAFTA partners rising as they rediscuss the treaty. The US’s requirement of higher US manufacturing content is particularly contentious. We continue to place a limited probability on a unilateral withdrawal from NAFTA by the US, despite the Trump administration’s ongoing threats. We think that Congress will act as a safeguard against NAFTA’s demise, in tandem with business interests (such as the auto sector). The November 2018 mid-term elections are now in sight, and that should mean progress on stalling NAFTA renegotiation. Another stumbling block is the Mexican general election in July. Meanwhile, the US’s relationship with China should also be monitored closely as there are signs of rising low-level tension that could manifest itself in increased trade tariffs on certain goods. Still, ‘trade war’ is not our base-case scenario. Another risk lies with the next government shutdown deadline, sometime in early March. The most recent government shutdown episode, just this month, shows that brinkmanship remains the norm in Congress, and there is a risk it could reappear ahead of this high-adrenaline deadline. But we would stress there are also two important positive upside risks that could mitigate some of these uncertainties. First, the US could experience a leverage boom that translates into higher consumer spending. Our forecast of 2.7% consumer spending growth in 2018 (the same as in 2017) remains relatively conservative and suggests spending growth will moderate somewhat after a particularly healthy holiday shopping season. But there are signs that banks are continuing to loosen their credit conditions, particularly in consumer credit. While consumer credit has been on the rise lately, it still only represents 4.1% of GDP, compared with 5.4% in 2007 – suggesting there is some catch-up potential. |

US Unemployment Rate, 1988 - 2018 |

| An area worth watching closely is the home -equity line of credit products, which have been mostly sidelined since the global financial crisis. But their return, at a time when rising home prices are favouring their use, could herald a step-up in consumer borrowing (however, this could increase financial-stability risks later down the road, too). Another related sector is mortgage lending.

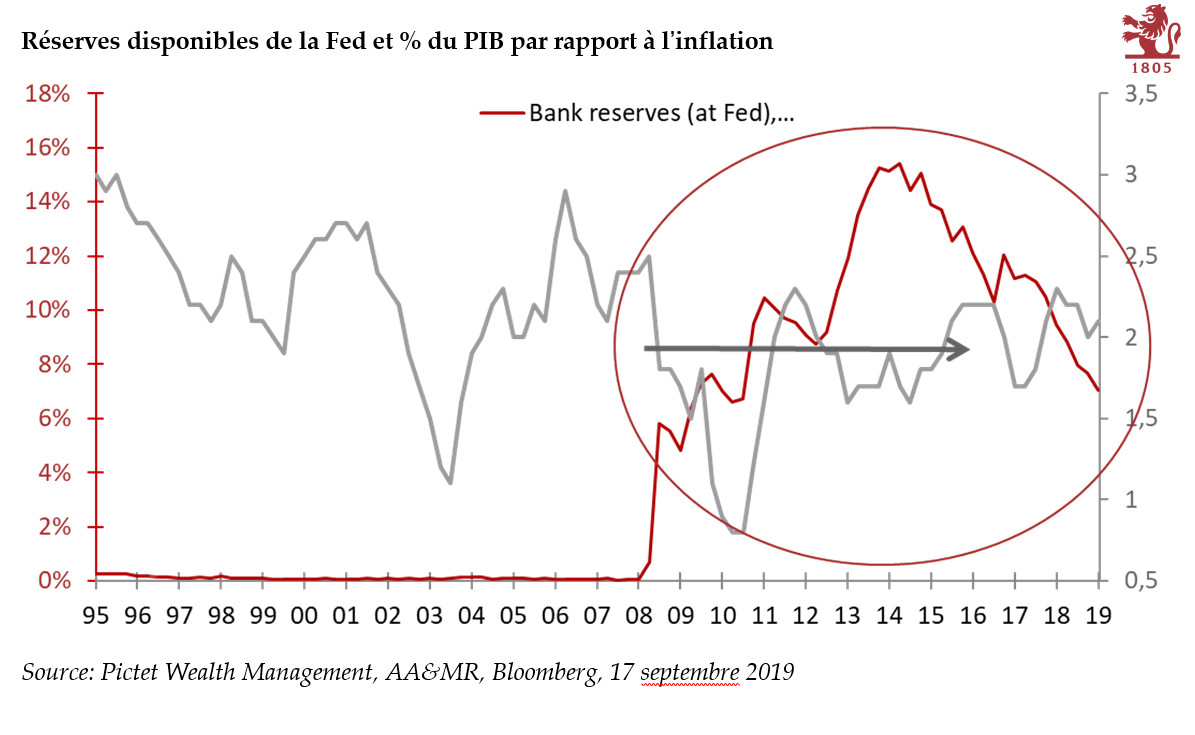

Our forecast of 3.0% growth in residential investment in 2018 is again conservative: a mortgage lending boom could easily boost the housing sector more than we expect. The second upside risk lies with politics, given current expectations are very low. In particular, there is the possibility of increased federal government spending. Discussions are ongoing to increase defence spending, especially at Congressional level. This would be in contrast to President Trump’s rather inward-looking stance during his election campaign. More importantly, Trump is likely to put more focus on infrastructure spending (mentioning a USD 1.7tn spending package, leveraging federal money with private-sector money). We have limited hope in this regard due to the highly optimistic funding structure it seems to rely on, as well as political division. Still, we should not overlook the possibility of a large-scale infrastructure investment programme that boosts growth in 2019. To test the ongoing validity of our 2018 ‘3%, investment-led’ growth scenario, apart from the evolution of investment itself, we will closely monitor commercial and industrial (C&I) bank lending, which we expect to regain strength after some softness in 2017. Increased C&I lending should be acorollary of increased investment activity, even though we note that firms are generating plenty of cash internally, making recourse to bank loans less necessary, and bond market conditions have also been particularly favourable. But a slowdown in corporate profits, combined with still-slow demand for credit, would mean that our scenario of accelerating investment is off track. Fed: now expecting four rate hikes this yearWe now think the Fed will hike rates four times by a quarter point in 2018, bringing the interest rate on excess reserves (IOER) to 2.5% by year end. We expect two additional rate hikes in 2019, in March and June. We also believe that the Fed is currently reassessing the impact of the tax cuts on the economy, and is seeing them in a more positive light than in December, when it last met formally. We think New York Fed president Bill Dudley’s recent pronouncements are particularly telling in that regard, as he stressed the upside risks to the rate hike profile coming from higher expected growth and loose financial conditions. He even mentioned the risk of “over heating” in the economy. We think this hawkishness could spread to other Fed members. We expect little from the 31 January policy meeting (when no press conference is scheduled); but we expect communication from Fed officials to remain hawkish as they give speeches – especially if wage growth creeps up in the coming weeks. This could pave the way for an upward revision of the Fed dots (projections for Fed hikes this year) from three rate hikes to four hikes in March, when the new forecasts are released. A dot plot of four rate hikes would match our new Fed rate -hike scenario. As the Fed continues to tighten rates, we think it is highly likely that it will well telegraph its hikes, with one hike at each quarterly meeting foll owed by a press conference. The exception would be if there is a sudden tightening in financial conditions (something that is difficult to anticipate) caused, for instance, by a sharp drop in the stock market and / or a sharp widening in corporate bond spreads (in such circumstances, the Fed would pause rate hikes while gauging the impact of tightening on the economy). In the absence of such a shock, consistent, above-potential GDP growth should pave the way for the Fed to continue hiking in a predetermined, gradual manner. The question is now at what level the Fed would pause tightening. In short, we now think the real neutral rate level – which is currently near zero – could move up by 1 percentage point in the coming quarters as increased inves tment spending stimulat es productivity. That means the significant threshold for this Fed rate-hiking cycle is now 3% (1% real rate and 2% inflation). As an aside, we see limited chance that the Fed will revisit its current flexible inflation-targeting regime, despite recent talk of reviewing alternatives such as nominal GDP targeting or price -level targeting. Our view remains that the Fed de facto already incorporates some elements of price – level targeting. Its cautiousness on rate hikes is in large part due to its ongoing anxiety that inflation could remain low in the wake of recent poor readings. The question is whether Fed officials start to incorporate more from the financial-stability picture into their monetary decisions (deciding to hike rates to partially stem market excesses or slow the ramp-up in valuations). We note that anxiety about the financial markets is on the rise among Fed officials, although the Fed’s baseline is that it will not ‘lean against the wind’. But hints that the Fed will move in that direction could place upside risks on our Fed rate hike profile, particularly beyond 2019. |

Fed Dot Plot vs Current Market Pricing Futures, 2018 - 2020 |

Full story here Are you the author? Previous post See more for Next post

Tags: Macroview,newslettersent