[See also The Numbers Show Trump Win NOT Due to Racism and Sexism]

You can only understand the victory of Donald Trump and Brexit once you understand the failure of globalization …

Trump

Trump made rejection of globalization a centerpiece of his campaign. In his July 21st acceptance speech as the Republican nominee, he said:

Americanism, not globalism, will be our credo.

The Boston Globe bannered this headline on Thursday: “Trump won. Globalization lost. Now what?”

On election night, CNN’s Jake Tapper explained that many Americans voted for Trump because they are sick of the income inequality, globalization, and politics-as-usual that the status quo have given us. He pointed out that only a handful of people have gotten rich off of globalization, and a lot of people have been left behind.

Counterpunch wrote Friday:

The real meaning of this upset is that Wall Street’s globalization project has been rejected by the citizens of its homeland.

***

Trump voters had several reasons to vote for Trump other than “racism”. Most of all, they want their jobs back, jobs that have vanished thanks to the neoliberal policy of transferring manufacturing jobs to places with low wages.

Brexit

Similarly, Brexit was largely a vote against globalization.

For example, the Guardian ran an article in June explaining, “Brexit is a rejection of globalisation”:

Britain’s rejection of the EU. This was more than a protest against the career opportunities that never knock and the affordable homes that never get built. It was a protest against the economic model that has been in place for the past three decades.

***

Europe has failed to fulfil the historic role allocated to it. Jobs, living standards and welfare states were all better protected in the heyday of nation states in the 1950s and 1960s than they have been in the age of globalisation. Unemployment across the eurozone is more than 10%. Italy’s economy is barely any bigger now than it was when the euro was created. Greece’s economy has shrunk by almost a third.

***

Inevitably, there has been a backlash, manifested in the rise of populist parties on the left and right. An increasing number of voters believe there is not much on offer from the current system. They think globalisation has benefited a small privileged elite, but not them. They think it is unfair that they should pay the price for bankers’ failings. They hanker after a return to the security that the nation state provided, even if that means curbs on the core freedoms that underpin globalisation, including the free movement of people.

***

Torsten Bell, the director of the Resolution Foundation thinktank, analysed the voting patterns in the referendum and found that those parts of Britain with the strongest support for Brexit were those that had been poor for a long time. The result was affected by “deeply entrenched national geographical inequality”, he said.

There has been much lazy thinking in the past quarter of a century about globalisation. As Bell notes, it is time to rethink the assumption that a “flexible globalised economy can generate prosperity that is widely shared”.

But What Do the Experts Say?

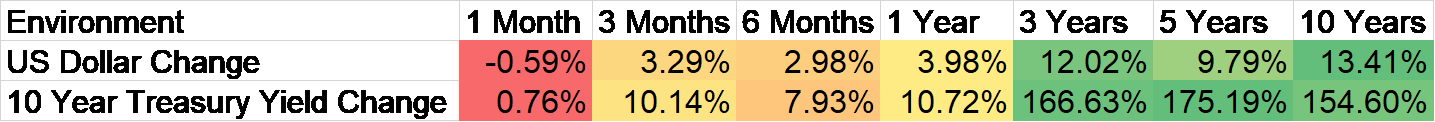

Mainstream economists, organizations and politicians – including the World Bank, International Monetary Fund (and see this), McKinsey & Company and Obama – now admit that globalization creates inequality. People worldwide are furious at runaway inequality … and it’s affecting elections globally.

The Bank of International Settlements – the “Central Banks’ Central Bank” – says that financial globalization itself makes booms and busts far more frequent and destabilizing than they otherwise would be.

The Economist pointed out in July:

Most economists have been blindsided by the backlash [against globalization]. A few saw it coming. It is worth studying their reasoning ….

David Autor, David Dorn and Gordon Hanson have documented how the costs of America’s growing trade with China has fallen disproportionately on certain cities. And so on.

Branko Milanovic of the City University of New York believes such costs perpetuate a cycle of globalisation. He argues that periods of global integration and technological progress generate rising inequality ….

Supporters of economic integration underestimated the risks both that big slices of society would feel left behind ….

The New York Times reported in March:

Were the experts wrong about the benefits of trade for the American economy?

***

Voters’ anger and frustration, driven in part by relentless globalization and technological change [has made Trump and Sanders popular, and] is already having a big impact on America’s future, shaking a once-solid consensus that freer trade is, necessarily, a good thing.

“The economic populism of the presidential campaign has forced the recognition that expanded trade is a double-edged sword,” wrote Jared Bernstein, former economic adviser to Vice President Joseph R. Biden Jr.

What seems most striking is that the angry working class — dismissed so often as myopic, unable to understand the economic trade-offs presented by trade — appears to have understood what the experts are only belatedly finding to be true: The benefits from trade to the American economy may not always justify its costs.

In a recent study, three economists — David Autor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, David Dorn at the University of Zurich and Gordon Hanson at the University of California, San Diego — raised a profound challenge to all of us brought up to believe that economies quickly recover from trade shocks. In theory, a developed industrial country like the United States adjusts to import competition by moving workers into more advanced industries that can successfully compete in global markets.

They examined the experience of American workers after China erupted onto world markets some two decades ago. The presumed adjustment, they concluded, never happened. Or at least hasn’t happened yet. Wages remain low and unemployment high in the most affected local job markets. Nationally, there is no sign of offsetting job gains elsewhere in the economy. What’s more, they found that sagging wages in local labor markets exposed to Chinese competition reduced earnings by $213 per adult per year.

In another study they wrote with Daron Acemoglu and Brendan Price from M.I.T., they estimated that rising Chinese imports from 1999 to 2011 cost up to 2.4 million American jobs.

“These results should cause us to rethink the short- and medium-run gains from trade,” they argued. “Having failed to anticipate how significant the dislocations from trade might be, it is incumbent on the literature to more convincingly estimate the gains from trade, such that the case for free trade is not based on the sway of theory alone, but on a foundation of evidence that illuminates who gains, who loses, by how much, and under what conditions.”

***

The case for globalization based on the fact that it helps expand the economic pie by 3 percent becomes much weaker when it also changes the distribution of the slices by 50 percent, Mr. Autor argued.

Steve Keen – economics professor and Head of the School of Economics, History and Politics at Kingston University in London – wrote Friday:

Plenty of people will try to convince you that globalization and free trade could benefit everyone, if only the gains were more fairly shared. The only problem with the party, they’ll say, is that the neighbours weren’t invited. We’ll share the benefits more equally now, we promise. Let’s keep the party going. Globalization and Free Trade are good.

This belief is shared by almost all politicians in both parties, and it’s an article of faith for the economics profession.

***

It’s a fallacy based on a fantasy, and it has been ever since David Ricardo dreamed up the idea of “Comparative Advantage and the Gains from Trade” two centuries ago.

***

[Globalization’s] little shell and pea trick is therefore like most conventional economic theory: it’s neat, plausible, and wrong. It’s the product of armchair thinking by people who never put foot in the factories that their economic theories turned into rust buckets.

So the gains from trade for everyone and for every country that could supposedly be shared more fairly simply aren’t there in the first place. Specialization is a con job—but one that the Washington elite fell for (to its benefit, of course). Rather than making a country better off, specialization makes it worse off, with scrapped machinery that’s no longer useful for anything, and with less ways to invent new industries from which growth actually comes.-

Excellent real-world research by Harvard University’s “Atlas of Economic Complexity” has found diversity, not specialization, is the “magic ingredient” that actually generates growth. Successful countries have a diversified set of industries, and they grow more rapidly than more specialized economies because they can invent new industries by melding existing ones.

***

Of course, specialization, and the trade it necessitates, generates plenty of financial services and insurance fees, and plenty of international junkets to negotiate trade deals. The wealthy elite that hangs out in the Washington party benefits, but the country as a whole loses, especially its working class.

And Clinton can’t claim ignorance, as a member of Team Clinton admitted in a leaked email that globalization lowers the wages of American workers:

You have (characteristically) gone right to the heart of the most difficult problem. In response to your specific question, over that last 15 years, the capacity of labor to demand a greater share of profits from productivity gains have been overwhelmed by several factors: 1) globalized wage competition as incomes have slowly equilibrated around the world ….

Coming Home Again?

The mainstream line is that globalization can’t be reversed. But the Guardian notes:

There are those who argue that globalisation is now like the weather, something we can moan about but not alter. This is a false comparison. The global market economy was created by a set of political decisions in the past and it can be shaped by political decisions taken in the future.

Ironically, the Washington Post noted last year that the giant multinational corporations themselves are losing interest in globalization … and many are starting to bring the factories back home:

Yet despite all this activity and enthusiasm, hardly any of the promised returns from globalization have materialized, and what was until recently a taboo topic inside multinationals — to wit, should we reconsider, even rein in, our global growth strategy? — has become an urgent, if still hushed, discussion.

***

Given the failures of globalization, virtually every major company is struggling to find the most productive international business model.

***

Reshoring — or relocating manufacturing operations back to Western factories from emerging nations — is one option. As labor costs escalate in places such as China, Thailand, Brazil and South Africa, companies are finding that making products in, say, the United States that are destined for North American markets is much more cost-efficient. The gains are even more significant when productivity of emerging countries is taken into account.

***

Moreover, new disruptive manufacturing technologies — such as 3-D printing, which allows on-site production of components and parts at assembly plants — make the idea of locating factories where the assembled products will be sold more practicable.

***

GE, Whirlpool, Stanley Black & Decker, Peerless and many others have reopened shuttered factories or built new ones in the United States.

Tags: Bank of international Settlements,Brazil,Capitalism,central banks,China,Donald Trump,Economic inequality,European Union,Eurozone,Greece,Harvard University,International Monetary Fund,International trade,Italy,New York Times,newslettersent,The Economist,Unemployment,World Bank,Zurich