Thoughts on the Japanese Currency Debasement (part 3)

In previous posts we looked on the following aspects of the recent Japanese currency debasement:

Overview: What different leading economists – Paul Krugman, Richard Koo, Adam Posen, Kyle Bass – think about the Japanese currency debasement and the way to more private spending and investing instead of paying down debt, an end of deflation.

Part 1: Japanese government bond yields did not rise (yet) as much as Kyle Bass expected and the Japanese current account is still positive while slower Chinese demand led to a negative Australian current account.

Part 2: What determines FX rates? or why could USD/JPY rise so much given that MoF interventions did not really exceed the ones of 2010 and 2011?

In this third part we cite a blog entry of one of the best academic blogger, Professor Noah Smith, an expert on Japan and a physicist by first education. He shows that Japan had only one lost decade between 1990 and 2000, but the period between 2000 and 2007 saw quite reasonable growth despite the liquidity trap.

Noah Smith writes in his Noahpinion blog

Noah Smith writes in his Noahpinion blog

“Paul Krugman rightly points out that Japan’s growth during the period of 2000-2007 – roughly, the Junichiro Koizumi era – was a lot stronger than most people realize, and was in fact even stronger than growth in the U.S.:

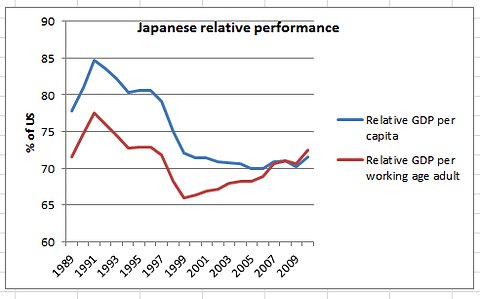

In the figure below I compared the ratio of Japanese to US GDP per capita (from Total Economy Database) with the ratio of Japanese to US GDP per adult aged 15-64:

(click to expand) Japanese GDP per capita and working age vs. US (source Paul Krugman)

Instead of a huge decline, never reversed, there’s a smaller decline, largely reversed. You can argue that Japan should have done better, continuing to converge on US levels. But the seemingly overwhelming failure you see if you don’t take demography into account just isn’t clear.

Quite right. Japan had one lost decade, not two.

Now, here’s the puzzle. What caused the Japanese growth speedup of 2000-07?

Remember, during that entire period, Japan was stuck in a liquidity trap. Here are interest rates:

And here’s inflation – or, rather, deflation:

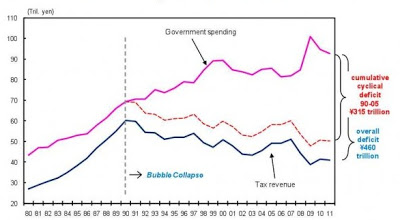

Did Japan stimulate its way out of the soldrums? According to the liquidity-trap version of New Keynesian economics, an increase in government spending should boost growth in this sort of interest rate environment. However, the period 2000-07 was actually a time of relative austerity for Japan! Japanese government spending decreased noticeably, in both absolute terms and as a percentage of GDP. Here’s the picture for spending levels:

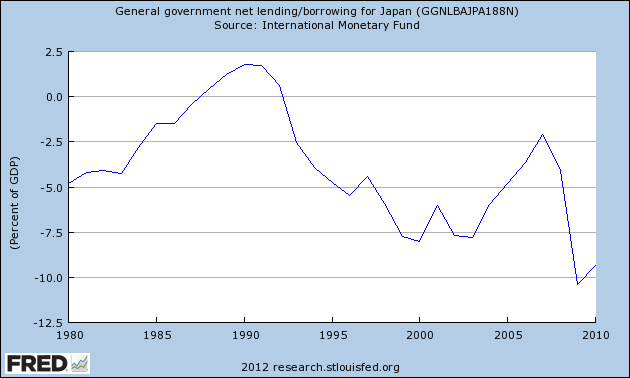

And here are deficits as a percentage of GDP (lower = bigger deficit):

The fact that the spending cuts and the growth speedup exactly coincide is probably a coincidence (unless the Confidence Fairy lives in Japan and never visits Europe). But the point is, austerity didn’t hurt Japan as much as we might expect, and the 2000-07 boom was definitely not caused by a sudden surge in stimulus spending. So the Koizumi era seems not to have been a Keynesian success story.(Update: Of course, I don’t want to confuse levels with growth rates here. The deficit was at its peak during 2000-2003. The “austerity” I mention was a decrease in the rate of growth of the deficit; the decrease in the deficit didn’t really come until 2004-2007. So it’s conceivable that the large deficits of 2000-2003 “jumpstarted” a recovery, or perhaps acted with a lag. But that leaves the question of why deficits suddenly started working after not seeming to do much in the 90s, in which growth kept falling even though deficits kept rising. And it also leaves the question of why the decrease in deficits in 2004-2007, when the interest rate was still at the ZLB, didn’t noticeably hurt the recovery.)

What about trade? Well, surging trade, much of it with China, probably helped:

But does this mean that Japan exported its way out of the recovery (a strategy that is certainly possible when the rest of the world is growing strongly)? No. Note that this chart is exports, not net exports. Imports surged too, so that Japan’s net exports – its balance of trade – didn’t really change much during the Koizumi years. Nor did the yen’s value against the dollar change much overall within this time frame, despite a well-publicized currency intervention in 2004. Then again, Japan’s current account balance did rise sharply, though more toward the end of the 2000-7 recovery period.

So the jury is still out whether the Koizumi years were a mercantilist success story, though it seems more likely that a boom in two-way trade, especially with China, fits the story much better. (Note that a larger volume of balanced trade provides increased gains from trade, which then filter through the rest of the economy with some multiplier effect, boosting investment and consumption.)

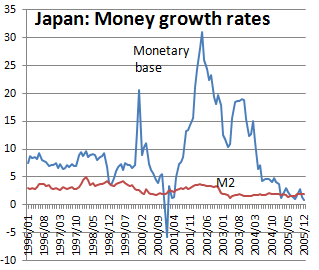

Are the Koizumi years a montarist success story, then? Some people credit the Koizumi boom to the Bank of Japan’s unconventional monetary policy (quantitative easing). Also via Krugman, here is Japan’s monetary base:

This looks like a big policy change, and it came at the beginning of the 2000-7 recovery period, not the end. On the other hand, as we saw above, Japan remained in or very near deflation for the entire period, and ever since (meaning that NGDP didn’t grow anywhere near the 5% that Scott Sumner and others claim is optimal). Also, inflation expectations increased very slightly, but stayed around 1%. So if quantitative easing helped, it did so through means that are not well-understood.

How about the “balance sheet recession” story? Well, Japan’s big banks, saddled with bad debts throughout the stagnation years of the early 90s, definitely went through a period of deleveraging in the late 90s and early 2000s:

But much of the growth of 2000-07 came during the deleveraging, rather than after it. Was the growth an effect of forward-looking expectations? Did companies and households see banks cleaning up their balance sheets, and assume that this would allow a return to economic health? It seems possible, I suppose. (Update: What about more general corporate debt levels? Well, data is spotty, but see here, here, and here. The picture is extremely similar to that of bank debt above…leaving the same open questions.)

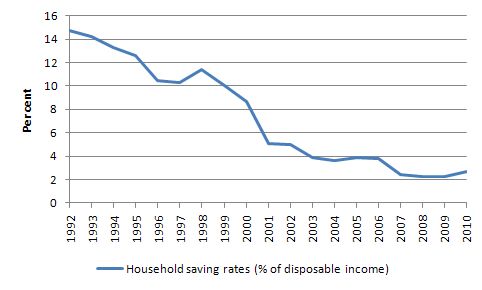

Japan’s household savings rate plunged in the 90s but didn’t do much in the 2000s.

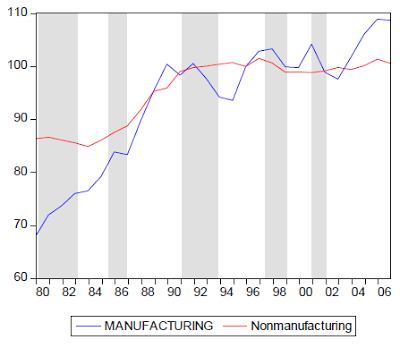

How about structuralist explanations? Japan’s Total Factor Productivity flatlined during the 1990s, an effect often attributed to “zombie” companies. But it didn’t really pick up that much when growth picked up, at least not in the service industries that structuralists think are the big problem:

That data is from Hoshi & Kashyap (2011). Note that there is a spike in manufacturing TFP from 02-05, so this could have been a driver of the boom.

Anyway, to wrap up: During the years of 2000-07, Japan grew quite quickly when measured properly (as GDP/working age population), substantially faster than the United States after accounting for demographics. However, during this entire time, it was stuck deep in a liquidity trap, with government spending decreasing and banks and companies deleveraging. Also, Japan did not experience a major improvement in its balance of trade, nor a large currency depreciation, nor an increase in inflation or inflation expectations. Additionally, Japanese services TFP remained flat.

What did happen during the 2000-07 boom included

A) an increase in balanced trade, especially with China,

B) a steep rise in household borrowing,

C) the cleaning up of bad bank loans,

D) a possible resumption of growth in manufacturing TFP, and

E) a short period of quantitative easing policy.

None of these factors seems to jump out at me as the obvious structural causes of the boom, given the above list of things we didn’t observe. I guess of this second list, (A) and (B) seem like the most intriguing.

But anyway, I regularly say things like “Japan confounds macroeconomic analysis.” Now you know what I mean…

Update:

After I wrote this post, I thought of one more possibility. Maybe the real mystery is not why Japan did well in 2000-07, but why it did badly in the late 1990s. If the late-90s recessions were caused by some sort of string of negative demand shocks – the Asian financial crisis, the BOJs interest rate hike, continued fallout from the 1990 bubble pop, etc. – then the outperformance in 2000-07 might just represent a “string-plucking” effect as Japan returned to trend, with corporations buying all the IT equipment that they had delayed buying in the late 90s. It’s still really weird that they stayed at the ZLB, with deflation, all through the recovery, though.

We add the most relevant comment by Matt Rognlie, PhD student in economics at MIT. Noah corrected his comments on households after that.

The upswing in household debt would be the most likely candidate, but unfortunately the graph you posted has data on debt-to-income for the UK, not Japan. (See, for instance, here.) It turns out that the debt-to-income ratio in Japan was relatively steady over the expansion, robbing me of one of my favorite explanations…

Given all this, my view is that the Japanese experience is best interpreted through the lens of demand. Suppose that we have a crudely Keynesian take on the Japanese slump, in which the downturn was simply a shortfall of aggregate demand. Then the “mystery” of the Japanese expansion is not much of a mystery at all; after all, it wasn’t an actual acceleration in GDP growth, just an acceleration in GDP growth relative to labor supply. And in a demand-constrained economy, perhaps there’s no reason we should expect changes in supply to matter at all! If households smooth their consumption, then the retirement of elderly workers will leave demand (and therefore demand-constrained GDP) unaffected, while the working-age population decreases. This is roughly what we see in the data.

All this is so crudely Keynesian that I’m a bit embarrassed to be writing it, but I do think that it can be embedded in a much more sophisticated model. Envision a riff on Krugman’s 1998 BPEA suggestion that the natural rate of interest was low due to the saving needs of an aging population; as the population ages and we approach the new steady-state age distribution, the liquidity trap will naturally abate.

35 comments:

Dimitar4:21 PM

Dimitar4:21 PM

How about privatization? Does it help explain anything?

Also how about financial reforms? The stock market seems to have been boosted by QE, could it have helped a bit the rest of the economy?

Noah Smith6:18 PMPrivatization: No.

Financial reforms: Not sure.

“E) a short period of quantitative easing policy”

short lived perhaps, but between 2003 – March 2004 the BOJ printed a then unprecedented (in peacetime) 32 trillion yen (about $2,500 for every person in Japan).

the MOF, which is the institution which conducts open market ops in Japan, used the 32 trillion yen to purchase approximately $320 billion in U.S. dollar denominated assets.

to what effect? it helped slow down the appreciation of the yen, which between 2001-04 only gained 19% against the dollar vs. the euro’s 50%+ rise over the same period. that no doubt helped Japanese exports.

and for all you conspiracy buffs out there that normally hang ont out on Zerohedge but have ventured over here for a change, it’s perhaps noteworthy that the BOJ/MOF action kicked off around the time of Ben Bernanke’s visit to Japan in March 2003.

Noah Smith6:18 PMWhy invoke a conspiracy? Milton Friedman inspired both.

How about exports of capital goods? Can it be somehow more special – Germany which is also an exporter of them did pretty well over the same period.

Rob Rawlings4:53 PM

“The fact that the austerity and the growth speedup exactly coincide is probably a coincidence”

right.

Greg6:10 PM

Greg6:10 PM

There was a pause in the long secular decline in hours worked per employed person from about 1998 to 2005 (FRED: JPNAHWEP).

There was also a small rise in employment-population ratio (JPNEPP, JPNEPRNA) from 2003 to 2007, and a rise manufacturing employment as a percentage of the total from 2005 to 2007 (JPNPEFANA).

Workers working longer hours, followed by increased employment, specifically in manufacturing. Yes, they ought to produce more each, so it’s no surprise that they did

This is a picture of increased labour utilisation, reduced hoarding, rather than increased productivity in the Solow residual sense.

All the statistics appear to have resumed their secular trends. I guess we’ll have to stay tuned.

Noah Smith6:17 PM

Noah Smith6:17 PM

But those things you’re talking about are just standard business-cycle correlations…they happen in nearly every boom everywhere.

Greg6:37 PM

Greg6:37 PM

So is the question “why did they happen to a greater extent in Japan than in the USA?”

Actually, changes in employment-population were about the same in the two countries. For the other two, the effect was bigger in Japan than the USA.

But Japan was growing faster than the USA, so we’d expect these things to be a big bigger in Japan…

Rob Rawlings6:43 PM

I have a qustion on “Japan grew quite quickly when measured properly (as GDP/working age population”

While I can see that if you have an aging population that GDP/capita would understate growth would not GDP/working age population overstate it ? With a static working population one generally gets growth by increased investment in capital. With a falling working population one could get output growth per worker without increasing the amount of capital at all.

Yes, this is true. But several caveats:

1. At the same time you have population aging, which means more old workers and fewer young ones. That works against the “capital glut” effect.

2. As the dependency ratio rises, people need to do more work outside of the formal sector, taking care of old people. That also tends to depress GDP per working age adult.

3. A “capital glut” like you’re talking about would tend to decrease investment and increase consumption. Actually, consumption was pretty flat, or even declining, as a share of GDP during the early-2000s boom:

http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/series/KCPPPGJPA156NUPNSo it’s still puzzling to me…

Rob Rawlings8:21 PM

In any case its clear that there was a marked improvement in performance in the 2000’s compared to the 1990’s.

If I was a Keynesian and looked at this chart (that tracks the deficit against unemployment)

http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/graph/?g=fpK

I might conclude that the govt used fiscal policy to manage unemployment quite well , never letting it get above 5%. “Austerity” in the 2000s was just less fiscal policy being required.

Could low interest rates just be a factor of an aging population (a tendency to save more as retirement approaches plus less investment opportunities as the population actually starts to decline)?

Perhaps it just took the economy a decade to adjust to an ultra low natural rate due to changing demographics. If so then the 2000’s may actually give us a model of how you can get (relatively) good growth in an economy where the demographics keep the interest rates low.

I might conclude that the govt used fiscal policy to manage unemployment quite well , never letting it get above 5%. “Austerity” in the 2000s was just less fiscal policy being required.

This would make sense…if it weren’t for prices. Why the heck was there still deflation? Why were interest rates still at the ZLB when Japan was growing faster than the U.S.? Keynesian theory doesn’t predict that…I don’t know of any kind of theory that does!

Could low interest rates just be a factor of an aging population (a tendency to save more as retirement approaches plus less investment opportunities as the population actually starts to decline)?

No, look at the graph I posted of private saving. It goes down, not up. Less saving should put upward pressure on interest rates, higher consumption (and more BOJ money creation to keep rates low) should put upward pressure on prices. Yet…deflation.

Perhaps it just took the economy a decade to adjust to an ultra low natural rate due to changing demographics.

Say more…

1. The household debt to explode with 10 % disposable income added per year, that is one hell of a demand booster. The BoJ to exclude the Shinkin, huuugh ? Like not counting Credit Unions in the US? Or Sparkassen in Germany.

2. TFP in the Service sector is highly misleading. It just means that wages didn’t go up. “The Economist” had a similar graph for Germany. Same nonsense.

3. To call a 7% GDP government deficit “austerity” is pretty creative. We didnt do that even through the worst reunification year.

BT London3:21 AM

It’s not just credit growth that matters, it’s credit acceleration. Look at your credit growth graph – you have acceleration from 2000-2009: first, a reversal of a decline, then flat, then an incline.

Steve Keen is always going on about credit acceleration as a big driver of growth.

-

I think your update at the bottom makes the most sense… No longer serious adverse shocks. But it’s still weird that the ZLB needed to be maintained and that inflation was so utterly absent.

Anonymous9:26 AM

Possibilites

Japan had its own “housing bubble” using profits to bid up housing prices to unsustainable levels rather than distributing the profit more broadly. A lot of money was lost. Housing purchased in places other than Japan (like Hawaii) was lost to the Japanese and transferred to other economies.

People make bad investments all the time and those get averaged in to the economy with the exception of bubble collapse. Bubble collapse synchronizes the losses. In normal times, losers can get back on their feet and start to make up the losses. After a bubble collapse, losses are so big and losers are so many, the losses cannot be recovered without high inflation to inflate away the losses. This is a major downside to pursuing interest rates that are too close to zero.

Is there an opportunity cost into play? Money that should have been distributed more broadly to limit household borrowing or more productively invested into provision of goods and services was instead squandered on bad housing investments with money taken out of circulation by financial interests.

Money supply and velocity

Under normal conditions, the monetary authority can regulate money supply and velocity by its actions because leveraging and de-leveraging by private actors averages to near near. The Fed simply tips the scales in one direction or another. After a large bubble collapse, the action of private actors are synchronized. They no longer average zero. The average is so far from zero that it simply overwhelms the ability of a government to level the scales quickly, either by fiscal or monetary policy.The government needs to do all 3: Fiscal Stimulus, Monetary easing and Regulatory policy that writes off bad debts and encourages inflation. Government needs to do a lot of all 3 not a little of one or two.

There is an interaction between fiscal, regulatory and monetary policy that is more important than the major effects independently. Because the interaction term is so large, metrics do not correlate well with any single factor.

jonny bakho

Anonymous10:23 AM

You motivate this post by noting that Japan grew relative to the US. Every ‘inconsistency’ seems to follow from this observation being out of place. I don’t know if these would be a solution, but several things occur to me:

1. Growth in the US was lousy from 2000-7. So what if growth in Japan was marginally better; it could still have been lousy. How was growth in Japan on an absolute level?

2. The chart compares Japanese growth after adjusting for demographics to US growth. What would happen if you compared J after demo to US after demo (especially in conjunction with #1)?

3. The slope starting at 2000 is definitely positive, but it’s not all that steep, particularly if you think of the slope prior to ~1990. Why would it be unreasonable to think that a few small things (listed in A-E) could account for a small increase?

In Japan during 1998-2002 NGDP growth averaged (-0.9%) and RGDP growth averaged 0.1%. The Japanese announced their plan of ryoteki kin’yu kanwa (QE) on March 19, 2001 and maintained it through March 9, 2006. During 2003-2007 NGDP growth averaged 0.5% and RGDP growth averaged 1.8%:

http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2012/02/weodata/weorept.aspx?sy=1997&ey=2007&scsm=1&ssd=1&sort=country&ds=.&br=1&c=158&s=NGDP_R%2CNGDP%2CNGDP_D&grp=0&a=&pr.x=66&pr.y=8

Where’s the mystery?

AN INJECTION OF BASE MONEY AT ZERO INTEREST RATES:

EMPIRICAL EVIDENCE FROM THE JAPANESE EXPERIENCE 2001–2006

Yuzo Honda, Yoshihiro Kuroki, and Minoru Tachibana

March 2007Abstract:

“Many macroeconomists and policymakers have debated the effectiveness of the quantitative monetary-easing policy (QMEP) that was introduced in Japan in 2001. This paper measures the effect of the QMEP on aggregate output and prices, and examines its transmission mechanism, based on the vector autoregressive (VAR) methodology. To ascertain the transmission mechanism, we include several financial market variables in the VAR system. The results show that the QMEP increased aggregate output through the stock price channel. This evidence suggests that further injection of base money is effective even when short-term nominal interest rates are at zero.”http://www2.econ.osaka-u.ac.jp/library/global/dp/0708.pdf

P.S. When has Sumner, or any Market Monetarist, ever said that 5% NGDP growth was optimal for all times and places?

Cool, thanks for the link! 🙂

1) The Takenaka Plan and its associated financial reform (esp. splitting of UFJ) was highly successful. Japan now has as well-regulated a financial sector as anywhere.

2) The dearth of uncertainty shocks post tech-wreck drove higher business investment through increased confidence (I’m polishing a working paper on this under I.Fujiwara)

I think you got these pretty well in the final summary of ‘the mystery is the 90s’. As always, Hoshi+Kashyap (2011) have the best work on the topic. Taka Ito and Andy Rose’s book also covers it nicely. Try Jenny Corbett (ER, 2012) for a summary of the ‘mystery’.

Oh, and demographics aren’t really relevant as both collapse and recovery were short/medium-term variations on a trend.

Send me your paper when you have it up online, and I’ll blog it! Sounds very cool.

Notice I cited Hoshi & Kashyap (2011) in the post… 🙂

Quite right, so you did. And cheers!

Anonymous10:03 PM

The population of working age adults in Japan is older than in the United States, and older workers are more productive, are they not? That could explain most of the story.

Matt Rognlie12:03 AM Noah corrected the post based on this comment.

The upswing in household debt would be the most likely candidate, but unfortunately the graph you posted has data on debt-to-income for the UK, not Japan. (See, for instance, here.) It turns out that the debt-to-income ratio in Japan was relatively steady over the expansion, robbing me of one of my favorite explanations…

Given all this, my view is that the Japanese experience is best interpreted through the lens of demand. Suppose that we have a crudely Keynesian take on the Japanese slump, in which the downturn was simply a shortfall of aggregate demand. Then the “mystery” of the Japanese expansion is not much of a mystery at all; after all, it wasn’t an actual acceleration in GDP growth, just an acceleration in GDP growth relative to labor supply. And in a demand-constrained economy, perhaps there’s no reason we should expect changes in supply to matter at all! If households smooth their consumption, then the retirement of elderly workers will leave demand (and therefore demand-constrained GDP) unaffected, while the working-age population decreases. This is roughly what we see in the data.

All this is so crudely Keynesian that I’m a bit embarrassed to be writing it, but I do think that it can be embedded in a much more sophisticated model. Envision a riff on Krugman’s 1998 BPEA suggestion that the natural rate of interest was low due to the saving needs of an aging population; as the population ages and we approach the new steady-state age distribution, the liquidity trap will naturally abate.

Noah Smith1:09 AMThanks for pointing that out! I thought you were dead btw…

Tags: Bank of Japan,Deflation,Japan Exports,Ministry of Finance,MoF,USD/JPY