- When will local production be cheaper than imported products?

- Do people have the money to buy these local products?

The eurocrats continue to claim that Greece and other weaker members are following the best route to gain competitiveness, especially because labor costs are falling. Labor, however, is only one part of the competitiveness story, the countries also need other production factors, notably capital, which is missing in the current capital crunch. Furthermore the labor share is about 50% and contains still pension schemes, unemployment insurances and other taxes, additional costs that might increase with austerity measures.

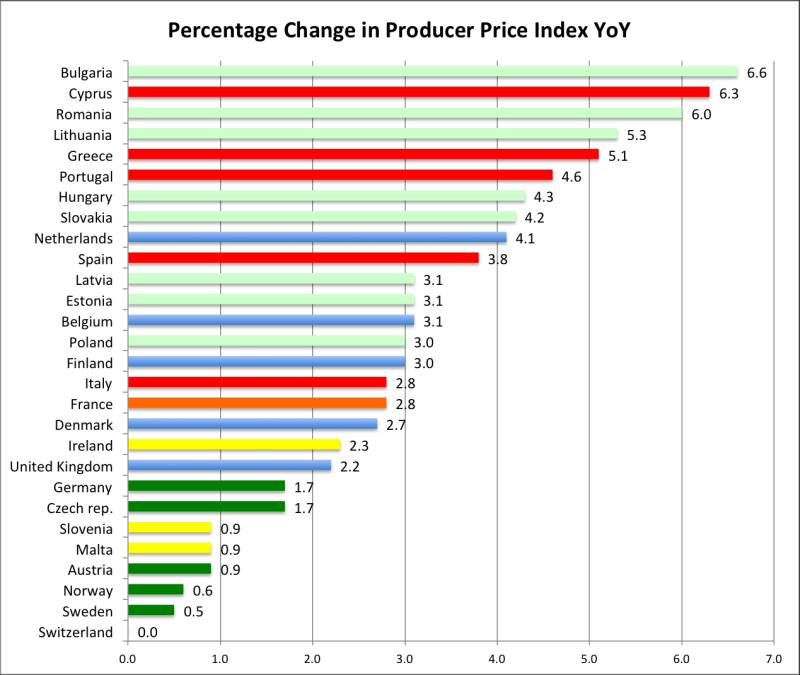

The best indicator of competitiveness are actually production prices: only if prices of the local industrial production are lower than imported German or Chinese goods, the weak countries will achieve competitiveness. We realized, however, that industrial production prices are rising far more quickly in the periphery than in Germany:

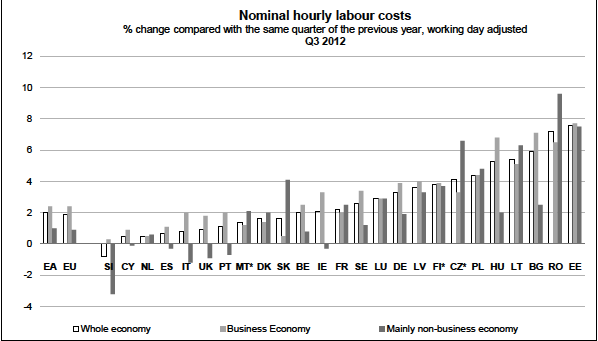

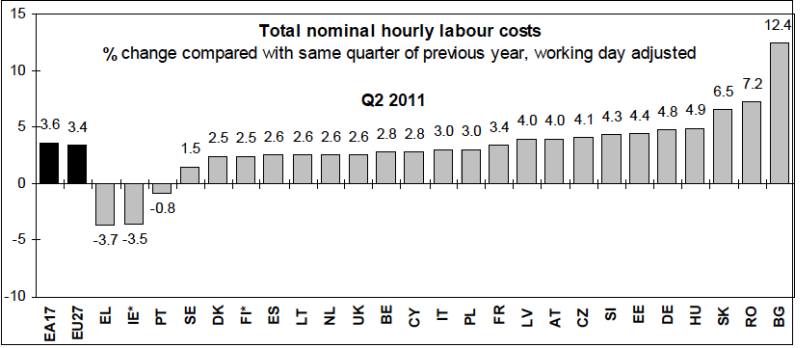

Two weeks ago, Eurostat released the industrial production price indices for October: just the Greek production prices started to fall (+4.1% YoY instead +5.1% in September), but the other problem countries still have similar high price increases as in September. On Monday, Eurostat published labor costs and wages. According to eurostat, labor costs rose by 2% in the euro zone in the third quarter. The ECB’s expectation of falling inflation seems to be still far away.

Moreover the Eurostat data shows that except from Greece and Slovenia, there is no country in which nominal labor costs are actually falling. After falling nominal wages in 2011, Ireland exhibits rising wages in 2012.

The ECB claims that labor costs are falling

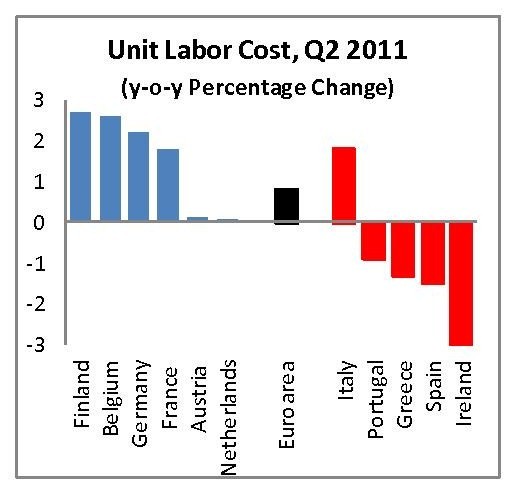

The ECB regularly claims that labor costs in the periphery are falling. In 2011, they used the strong rises in Spanish inflation, that includes the strong rise in Spanish production prices, to prove that Spanish labor costs were falling. They used real (inflation-adjusted) costs and the falling number of produced units: a nice “recursive trick” to calm the public.

Spanish nominal labor costs, however, were rising, as the Eurostat data shows.

Labor costs compared to real wages

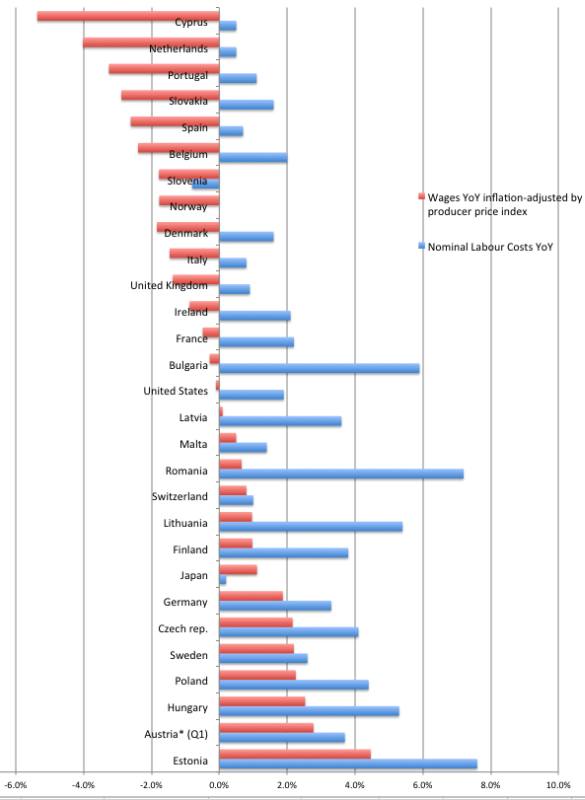

In the following we compare the change in nominal labor costs (in blue below) with real wages (in red). This gives an impression how much labor costs are rising in the different European countries, but also if people have still the needed purchasing power.

Instead of an inflation adjustment (“real”) with the consumer price index, we opted for the producer price index (“PPI”). The reason is that it gives a better impression of competitiveness and it gives an impression if employees are able to buy the goods they produce. In order to be competitive a peripheral country must be able to produce at a cheaper price than the competitors. Otherwise retailers prefer to import the goods from Germany or China.

The comparison gives the following picture:

We had to leave Greece out because it did not fit onto our graph: PPI-adjusted Greek wages fell by 12.3%.

Cyprus sees slightly higher nominal wages, but producer prices rose by over 6%, hence Cypriot real wages are down by over 5%. A similar picture in Portugal, Spain and Italy, where real wages fell between 1% and 3%.

Real wages descend most interestingly also in the Netherlands, in Belgium, Slovakia and the UK. The reasons are the bursting Dutch and Belgium real estate bubbles and the slowing in global trade and a tax increase in Slovakia. As for the UK, we already know about sticky inflation pressures.

Despite the slowing global growth, real wages are strongly rising in Austria, Germany, Finland, Sweden and in the Eastern European countries with their cheap-labor costs. The United States is situated somewhere in the middle (wage data FRED). Thanks to falling producer prices, Japan’s real wages are on the rise, despite the bad Japanese GDP data in the third quarter and Abe’s bashing of the BoJ and the yen.

Summary

The data makes clear that competitiveness for the peripheral countries is a very long way away. The first thing to be destroyed is purchasing power, consumer spending and then employment, because people do not have the money to buy the goods.

Only after that nominal wages will fall. After a long years, production prices will start to fall (relative to Germany). Finally also the combination of quality and production prices might show a better mix. Slovenia is now the next country that has joined Ireland and Greece in reducing nominal wages. As we have seen, yet without success in reducing production costs and becoming competitive.

By the next Eurostat labor costs release at the beginning of 2013, even Spain and Portugal should finally see lower nominal wages. But success in reducing production costs and real competitiveness will still be far away.

We think that most peripheral countries will need at least twenty years inside the euro corset to achieve this final goal, if they ever succeed.

The second take-away from this post is that there is no euro crisis, but just a European periphery crisis. At least, as long the French real bubble does not follow the Spanish, Danish and Dutch housing busts.

Are you the author? Previous post See more for Next postTags: Cyprus,ECB,European central bank,Greece,Ireland,Labor costs,labour costs,Netherlands,PPI,Producer Price,purchasing power,Switzerland