page 2

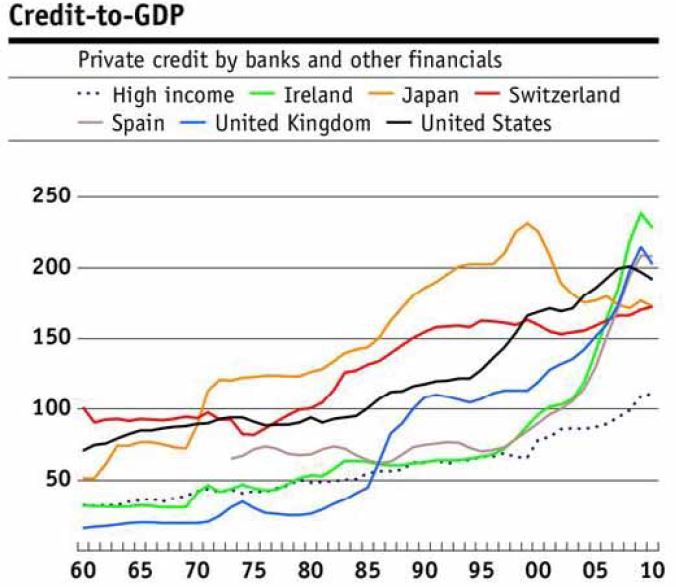

will see, making sense of this development is less trivial. To get a broader perspective on this question let us enlarge the picture shown in Figure 2b. Figure 3 provides the international dimension.

As is clearly visible, there has been a substantial built-up of credit relative to GDP on a global scale over the last decades. There are some notable differences in the size, timing and scope of this development between individual countries but the general direction is the same. Ominously the upward trend was particularly steep in the run-up to the recent financial crisis in those countries that were subsequently most heavily affected (US, Ireland, Spain, UK).

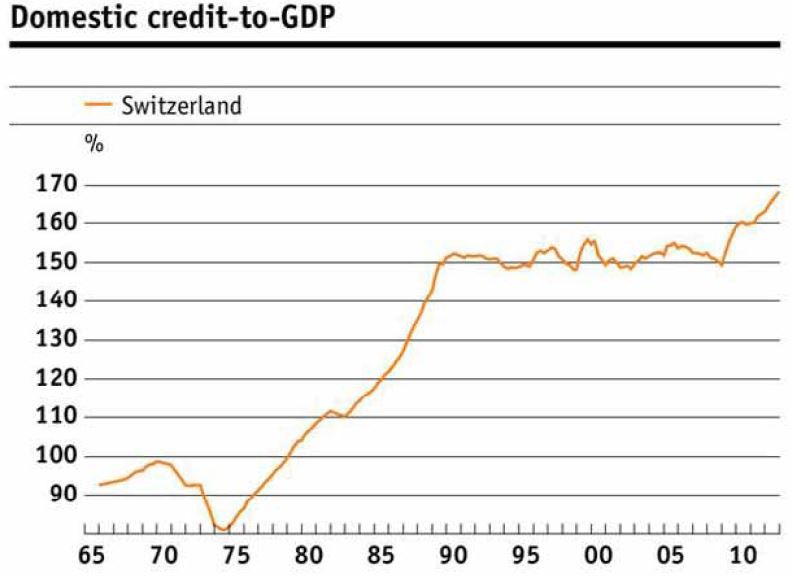

Figure 4 looks at the Swiss data from an earlier starting point. Here one is struck by the fact that the recent significant upward trend in the credit-to-GDP ratio has been preceded by an even more spectacular jump during the 1970s and 1980s, pushing the ratio to about 150% – a high level in international comparison.

During the 1990s, it then fluctuated around this mark. From 2000, we again observe an increase in the ratio1, at accelerated speed since 2009, such that, as of today, the ratio has reached about 170%.2 This more recent upward trend seems to be continuing unabated. How can we understand these developments? And can this understanding form a basis for predicting the likely future evolution of this variable in Switzerland? These are the questions I would like to focus on in this speech. To begin with, let me argue that if the dynamics in credit-to-GDP observed since the 1970s

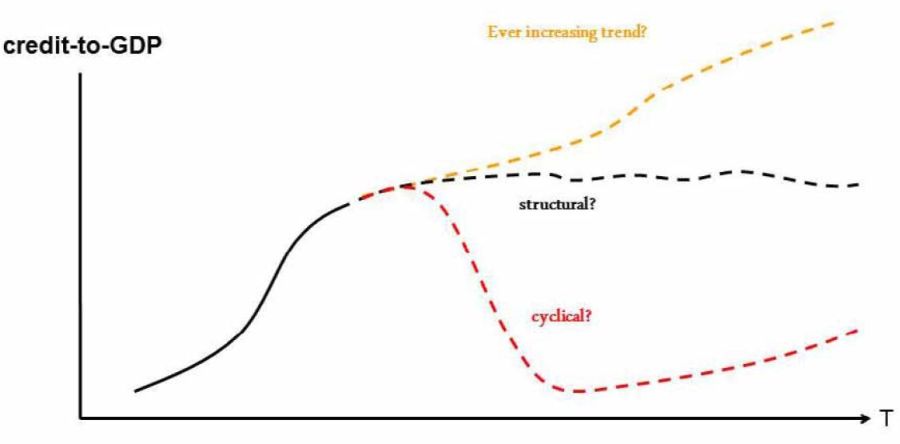

cannot be construed as an ongoing trend, the recent development must either be viewed as a structural adjustment to a new plateau – which seems to have been the case until 1990 – or as a cyclical upswing to be followed by a later correction. Schematically one can describe these possibilities in terms of Figure 5.3

Figure5: Current trend in credit to GDP: a structural shift or a cyclical upswing? - Click to enlarge

In the first case, the implication is that at some point, credit volumes will be growing in line with GDP again. This could be either the result of an acceleration of nominal GDP growth at constant credit volume growth, or of a moderation of credit growth to adapt to the long run growth rate of nominal GDP. In the second case, that is if the situation is rather one of a cyclical upswing, then clearly credit growth will have to undershoot nominal GDP growth for many years in the future. In both cases the present situation with credit growth significantly exceeding nominal GDP growth is not sustainable. However, the challenge to the financial industry to adapt to a much lower growth of credit is clearly larger in the second. This holds even if a harsh backlash in the form of an outright crisis can be avoided.

Unfortunately it is not possible to precisely ascertain where we stand and what the future holds in store. Nevertheless, I will try to bring some clarity to the issue by examining – first – possible explanations for an increasing credit-to-GDP ratio (section 3), then by assessing their explanatory power in the Swiss case (section 4). Section 5 will conclude.

- Between 2006 and 2008, the ratio temporarily decreased, as a result of the strong growth of GDP in this period. [↩]

- In this context, it is important to note that a vast majority of outstanding loans in Switzerland are granted as mortgages (mortgage volume to GDP: approx. 140%). The discussion of the Swiss situation will thus focus mainly on mortgage loans. [↩]

- As a third scenario it is also conceivable that there is a structural shift during which credit overshoots temporarily. This would also imply a certain correction down the road. However it would be clearly a less pronounced one than in the pure cyclical case. [↩]