The G7 heads of state summit has begun. The host, Japan’s Prime Minister Abe began with doom and gloom. Accounts suggest he warned of the risk of a crisis on the scale of Lehman if appropriate policies are not taken. It is not clear to whom Abe was addressing. It may not have been the other heads of state. It may have been a domestic audience Abe had in mind.

The G7 heads of state summit has begun. The host, Japan’s Prime Minister Abe began with doom and gloom. Accounts suggest he warned of the risk of a crisis on the scale of Lehman if appropriate policies are not taken. It is not clear to whom Abe was addressing. It may not have been the other heads of state. It may have been a domestic audience Abe had in mind.At the finance ministers and central bankers meeting last week, Japan’s Aso indicated that contrary to speculation, the retail sales tax hike would still be implemented next April. However, the opt-out has always been a serious crisis on the magnitude of Lehman’s demise. The Abe government is believed to be putting together a fiscal support package.

Reports indicate that there was not a formal push back against Abe’s use of crisis, but at the same time, it does not seem that his assessment was widely shared. Abe’s presentation included the fact that commodity prices fell 55% between 2014 and the beginning of this year, which matches the decline in prices in the 2008-2009 period. There is arguably a significant difference between the two periods. The first was a demand shock. The second was a supply shock.

Abe called on his guests to avoid another global crisis. Who can disagree with that? The solution is unlikely to be found with greater coordination. Countries are in different cyclical positions and have different mixes between savings and investment. The G7 is unlikely to go beyond the G20 call for countries policy room to use it. This is a call to current account surplus countries and balanced budgets like Germany to boost domestic demand.

Is the call to avoid another global crisis a plea to the Federal Reserve not to hike rates? In a word, no. The Federal Reserve argues that gradual rate hikes now, as conditions permit, will reduce the need for more aggressive hikes later. The Vice President of the ECB seemed to endorse a Fed hike earlier this year as a sign that the world’s largest economy is sufficiently strong to justify it.

Indeed, despite the talk of a secret Shanghai Agreement in late-February to stabilize the dollar and defer a rate hike (some add that it was to allow the Chinese to weaken the yuan though the yuan appreciated against the dollar throughout Q1), most of the G7 countries (and others) would seem to welcome a Fed hike. Higher US rates would ostensibly reduce pressure on other countries to ease monetary policy further. The G7 and G20 have recognized that monetary policy alone should not be relied on to achieve strong, sustainable and balanced growth.

Abe, even if he teamed up with Canada’s new prime minister to push for fiscal more fiscal support, is unlikely to find strong support. Germany and the UK, for example, resist. Italy may be more sympathetic, but it recently was given more time from the EU on the fiscal front The US budget deficit may grow this year to 2.9% of GDP from 2.6% in 2015.

There does appear to be two areas that there is agreement in the G7. Although the draft statement does not include a reference to the UK referendum at the end of next month, it seems widely acknowledged by the heads of state that Brexit would be a significant disruptive force.

The other issue that there is agreement is on Japan’s maritime proposals. Essentially the proposals are principles for resolving the territorial disputes in the Pacific. This is the recognition of international law as the basis for claims; that force should not be used. Instead, peaceful means including legal procedures should be used.

Obviously, these proposals are a way for Japan to seek support for its position vis a vis China. They sound uncontroversial, but there is more than meets the eye. For example, the unresolved claims were at a low ebb until the Governor of Tokyo bought disputed islands, and then the central government nationalized them.

China was willing to let a sleeping dog lie. Why? Because Chinese officials strongly believe the PRC will be in a more powerful position in five years and ten years than today, so why to resolve the issues now. However, if Japan or the Philippines recognizes the same likely trajectory of power and wake the sleeping dogs, then China is forced to respond And all the more if there is a domestic trade off for Chinese officials between economic liberalization and orthodoxy in foreign policy and politics.

The former Philippines government brought the dispute to the Permanent Court of Arbitration in the Hague. A judgment is expected later this year. It is a highly technical issue that partly revolves around how international law defines “islands.” China has used its soft power, and tapped into anti-US sentiment, to secure a number (40?) countries that support its claim. The court’s decision is not a popularity contest. China may be best served by convincing the new Philippines government to withdraw its case and resolve the dispute bilaterally.

One would not know it from reading the US press, but China is not the only one that is reclaiming land and building installations on shoals in the disputed area. The recent election in the Philippines may offer China an opportunity for a rapprochement. On the other hand, the new government in Taiwan was at least in part elected on a platform seeking a less close relationship the mainland. At the same time, the US has lifted its long arms embargo against Vietnam. Chinese officials are concerned that the US pivot to Asia and other actions in Asia are aimed at containing it.

An underlying tension is between the US-led Open Door and the more traditional spheres of influence. China’s claim to a wide swathe of the South China Sea, which Vietnam, the Philippines, Brunei, Malaysia and Taiwan also claim as theirs, can be understood it seeking a sphere of influence similar to Russia’s claim on Ukraine and other parts of central Europe. Europe sometimes seems a bit more sympathetic to spheres of influence but tends to embrace the Open Door (free mobility of goods, services, capital, and information).

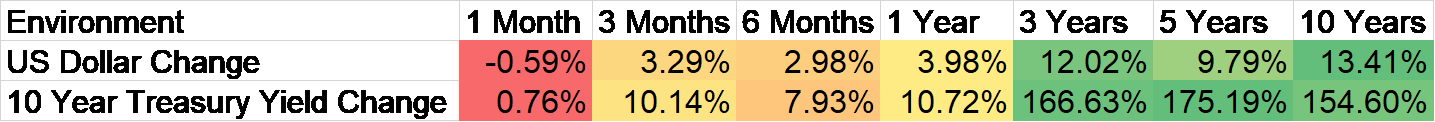

Ultimately the G7 summit cannot and will not unveil new cooperative initiatives. The desynchronized business cycle produces significant divergences that prevent a single solution. As host, Abe has a platform to pursue his domestic agenda. By Japan’s preferred measures, the dollar-yen exchange rate is stabilizing. The dollar has been in a two-yen range for the better part of three weeks now. This would seem to indicate less pressure to intervene. Concerns about the global economy do not seem to be sufficient at this juncture to prevent the Fed from hiking rates in the June-July period.

At the same time, the dollar’s strong uptrend has broken, and on a broad trade-weighted basis, the it is nearly 6% off its early February multi-year peak. The challenge for most low and medium countries lies not so much with the decline in commodities that Abe noted, but with the capital markets and the currency mismatches that stem from dollar borrowings.

Tags: Abenomics,China,newslettersent