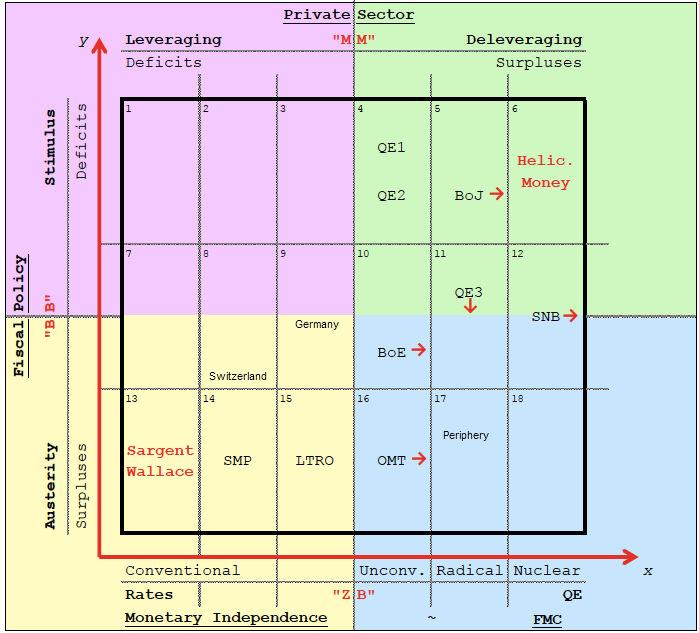

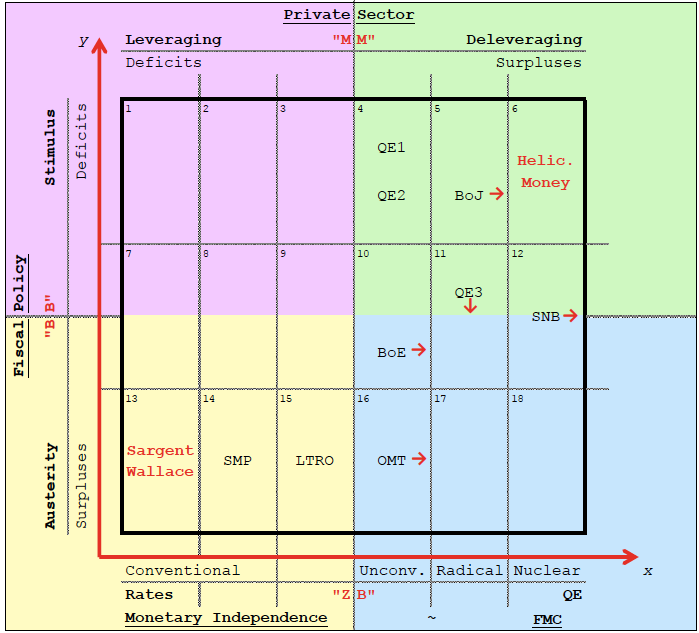

The newest paper by McCulley and Poszar “Helicopter Money: or how I stopped worrying and love fiscal-monetary cooperation” is often cited by leading economists, e.g. Eurointelligence or Paul Krugman in “Shinzo and the helicopters”. It presents fiscal policy and monetary policy divided in four areas along these two criteria. These two criteria correspond to fiscal and private spending, which is not by coincidence. The final aim of the authors is so-called “monetary and fiscal policy cooperation”.

The essentials:

- No distinction between households and firms: both are “private sector”. The reason for this is that firms do not invest if households do not spend enough. That both private sector components are leveraging does not imply deficit spending; in the sum they are leveraging. Still it holds that households finance investments and current account surpluses.

- “MM”: the Minsky Moment distinguishes between leveraging of the private sector (conventional business cycle with positive animal spirits) and de-leveraging (private sector prefers to pay down debt, negative animal spirits).

- “BB” Balanced Budget separates fiscal surpluses – or more austerity to fiscal stimulus.

The purple area:

- Is part of the conventional business cycle (private leveraging) during which, via positive animal spirits, private debt could increase and inflation slowly emerges.

- The rest of the world must have current account surpluses, otherwise these twin deficits would not be possible.

The yellow area:

- Is part of the conventional business cycle during which public debt is reduced – through sufficient growth and private leveraging.

- If leveraging becomes too big and inflation is high, rate hikes are required – with the extreme case of Sargent Wallace’s “Policy-ineffectiveness proposition” / “Some Unpleasant Monetarist Arithmetic”

or the “Volcker moment” where fighting against inflation is more important than growth. Policy maker would accept even a recession.

The blue area:

- Both fiscal austerity and private deleveraging lead to economic depression, a debt deflation/ deflationary spiral.

- Except in a special case – typically when being in a (near) fixed currency environment – policy makers will avoid the blue area at all costs.

- Fiscal policy remains the sole measure to get out of the blue area because monetary policy can only influence the price but cannot create demand.

- The ECB’s OMT allows for “crowding in” despite austerity measures.

The green area:

- Since the private sector wants to reduce debt, the government remains the principal bidder for funds.

- Unconventional measures, called quantitative easing (QE1, QE2), asset purchases of securities are used to stimulate private borrowing.

- Radical measures (e.g. QE3): the policy makers continue with unconventional measures even if the economic recovery has started. This reverse Volcker moment (El Erian, 2012) is exactly the opposite of the Volcker moment above.

- Nuclear measures: both monetary policy and fiscal policy used to raise nominal demand, “helicopter money”: in this case more fiscal debt is monetized.

- Measures mentioned only in a footnote, are foreign asset purchases and a limitation of the exchange rate by the central bank, only a small arrow associated with “SNB” is shown. The arrow shows that this measure goes even further. It is beyond nuclear.

- Opposed to the graph and what the authors suggest, the Swiss private sector is not de-leveraging, but actually leveraging.

Our extension: ECB’s and SNB’s monetary dilemmas

There are two central banks with clear policy mismatches.

ECB: While Germany is seeing fiscal surpluses and its private sector is leveraging (yellow sector), the periphery sees deleveraging and austerity (blue debt deflation sector). This leads to the policy dilemma in which Germany needs tightening but the periphery needs helicopter money. Therefore, the periphery and France cannot be printers and cannot apply monetary and fiscal cooperation.

SNB: While the Swiss private sector is strongly leveraging – as opposed to what McCulley and Poszar are describing.

With twin surpluses, Switzerland is actually in the yellow sector, but the SNB is doing a “beyond nuclear” monetary/fiscal policy mix. However printing is not possible when the private sector is leveraging, because it will eventually cause inflation. This mixture is only sustainable in the longer term if the U.S. and the periphery come far into the purple sector again and end the private deleveraging, with the effect that the EUR/CHF will rise again. Even in this case, Swiss inflation is possible; however, the SNB will be able to sterilize and/or sell its reserves higher than 1.20.

Monetary Fiscal cooperation extended with Switzerland, Germany, Periphery (G. Dorgan based on McCulley, Poszar (2012)

Richard Koo Details

McCulley, Poszar compared to Richard Koo

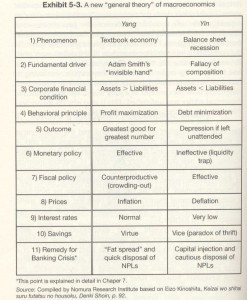

It is most interesting to compare McCulley, Poszar with Richard Koo’s “New General Theory of Macro Economics”.

Yang = Leveraging of private sector

Yin = Deleveraging

As opposed to McCulley/Poszar, Richard Koo claims that monetary policy is ineffective and only the fiscal part of “helicopter money” works.

Monetary policy ineffectiveness during QE2

Monetary expansion is only useful, when the recipients are ready to use the new printed money for leveraging and when markets are ready to give them the monies and do not want to export them because investment opportunities abroad are better. Twin deficits are only possible when the rest of the world has current account surpluses. With the sinking Chinese and Japanese surpluses, this might stop in the next years. If growth and productivity gains are not sufficient, then many developed countries will continue deleveraging.

One major issue is the question of who obtains the newly printed monies. According to Austrian economists, the first to obtain newly printed money are the quickest, like investment banks, who are then able to generate nice margins. For the real recipient, the underwater home owner, not much remains.

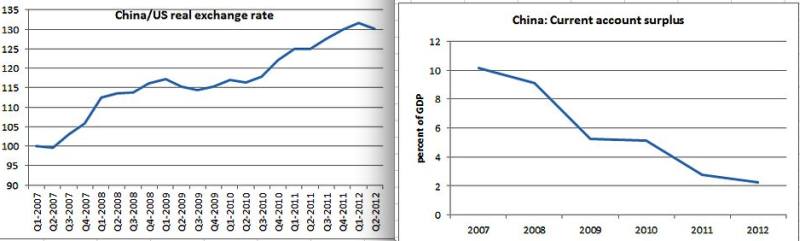

In 2010 (QE2), the Fed bought U.S. treasuries, unlike in 2008/2009 when it was mortgage-backed securities (QE1). In 2010, China and other emerging markets were still in the purple sector, they were leveraging and still under the Chinese and other governments’ stimulus packages of 2008/2009. This led to big growth, whereas U.S. households were not ready yet for leveraging, especially when they saw gas prices soaring. The newly printed monies left the U.S. and went into emerging markets, during the so-called “currency war”.

As reaction to the currency war and resulting high inflation, emerging markets needed to go into the “Sargent Wallace” sector and hiked rates. Together with the unfolding European debt crisis, this destroyed growth especially in South America and partially also in China. To fight against inflation and the currency war, the PBoC had to revalue the Renmimbi by 15%. Together with wage inflation, this led to lower Chinese competitiveness, the current account surplus (when compared to GDP) strongly decreased. The euro zone debt crisis and austerity caused a typical Austrian boom-bust cycle in the emerging markets. The U.S. won the currency wars.

The second issue is the availability of current account surpluses in the rest of the world. These surpluses must be there, otherwise there would not be anybody to finance the U.S. in the purple sector, nobody that would finance the twin deficits. Unfortunately the Chinese current account surplus is far smaller now when compared to GDP, countries like India, Australia or New Zealand are even in the red.

Only countries like Russia, Germany, South Korea and Switzerland still have high current account surpluses. Germans, however, are supposed to spend, to leverage, so that the European periphery comes out of the woods. Germany’s surplus is too small to finance both the U.S. and the periphery.

Who will finance helicopter money, if not China?

With far smaller future current account surpluses, it is open to debate if China will continue to buy U.S. treasuries. China is already switching more and more to gold, an investment, that is neutral and does not help any country in particular, some speak of the implicit introduction of a new gold standard, at least a third reserve currency. On the contrary, gold is associated with the growth of emerging markets. With time, the consumption of more and more parts of the population increases and with rising oil prices, one day, China will not have a current account surplus any more. Then it is time for other countries to do austerity and leave the purple sector into either the yellow, green or even blue ones.

If the U.S. continues to run twin deficits, we also see the risk that China or Japan will change existing treasury holdings into gold and direct investments that yield far more than US treasuries. In a decade, the Renmimbi might become the fourth major reserve currency with the euro and the U.S. dollar. This will reduce the holding of U.S. treasuries at central banks and increase yields.

Once all emerging markets reduce their savings rate and no longer have current account surpluses, but start consuming, the purple sector will not be available any more for developed economies. Depending on their productivity, certain developed economies will be situated in the yellow sector and tighten monetary policy. Two such countries are Germany or Switzerland, they have twin surpluses and will need higher interest rates when finally the Chinese produce for the local market and less for export.

Using fiscal stimulus when monetary policy is ineffective

Hence, monetary expansion is only useful when the recipients are ready to use the monies for leveraging and when markets are ready to give them the monies and do not want to export them because investment opportunities abroad are better.

Fiscal stimulus is a solution that is not handicapped by a missing wish to leverage and the possibility to export the monetary expansion. In particular, during phases of de-leveraging and low spending, the stimulus mostly remains in the local economy.

Hence, with the combination of fiscal and monetary policy, helicopter money does not always work.

See more for

5 comments

Skip to comment form ↓

DorganG

2013-01-23 at 09:11 (UTC 2) Link to this comment

None the less, there are voices that China will continue to finance the U.S. because Chinese leaders are too cautious to promote a social safety net and consumer spending and that Chinese savings rate remains high – maybe also because Chinese live in an authoritarian regime.

GrkStav

2014-01-08 at 06:21 (UTC 2) Link to this comment

You appear to have misunderstood (or, worse purposefully misconstrued) the “helicopter money” policy option, as presented in the paper by McCulley and Poszar that you are critiquing..QE2, and 3 are irrelevant as examples of the policy mix advocated by McCulley and Poszar as they were not accompanied by fiscal expansion. You also seem to operate under the assumption that the U.S. government, for example, literally borrows its own dollars back from e.g. China to finance its operations. Clearly, it does not, and it need not. The “Helicopter Money” policy-mix option is to be used by e.g. the U.S., the U.K. and Japan in the face of continuing private sector de-leveraging. It is not meant to spark private-sector leveraging.

China is not currently financing the U.S. anyway; it is choosing to exchange non-interest bearing (Federal Reserve Notes) for default-risk-fee liquid interest-bearing (T-bills) US$ denominated financial assets. “It” acquires the former as a result of maintaining a substantial trade surplus with the U.S.. Why it would choose to use them to buy Gold, e.g., instead of T-bills is a mystery.

George Dorgan

2014-01-08 at 06:42 (UTC 2) Link to this comment

Thanks, QE3 is still in the green sector (monetary/fiscal expansion), but no explicit “helicopter money” like Abenomics. The U.S. is still running fiscal deficits, just less than before.

I adopted the title for the critique, you are right, I criticize the effectiveness of monetary expansion in a global context.

DorganG

2014-01-09 at 19:20 (UTC 2) Link to this comment

You are right, I have corrected things a bit, because they got misunderstood. Please reread.

Be aware that the U.S. was doing rather neutral fiscal policy, 4% deficit is less than previously, but still a lot.

McCulley and Poszar put the U.S. into the green sector.

GrkStav

2014-01-10 at 00:46 (UTC 2) Link to this comment

The U.S., by all accounts, has not (yet) attempted the combined monetary&fiscal policy options #6 (“helicopter money”) or #12. The ineffectiveness of unconventional, radical, and even ‘nuclear’ monetary policy (as such) in the face of a deleveraging private sector and non-aggressively expansionary fiscal policy was a major point of McCulley and Poszar, if I understood them correctly. Given current “political” and ‘ideological’ realities, it is unlikely that policy option #6 will be pursued anytime soon. On the other hand, option #12 may become a reality, so long as there are no further net fiscal contractions (no net government spending reduction, no net tax increases). By the way, the (new) last sentence does not make sense to me. It appears that the conclusion ought to be: “Hence, with the private sector deleveraging, the combination of monetary and fiscal policy denoted as ‘Helicopter Money’ works for the kinds of countries and economies (relatively large and relative ‘closed’) McCulley and Poszar specified”.