During his recent presidential campaign, Donald Trump has repeatedly floated the idea of eliminating personal income taxes and replacing them with tariffs on imports. The proposal, which was never developed in a detailed and coherent plan, was met with hostility by mainstream media and analysts. The latter did not consider the proposal serious enough, because (i) it would be almost impossible to make up for the lost revenue from the income tax with higher tariffs, and (ii) sky-high tariffs would have very negative consequences on international trade and domestic consumers, while shifting a larger share of the tax burden onto low- and middle-income households.

Some Austrian school economists met the proposal with scepticism too. Ryan McMaken argued that the US needs a significant cut in taxes overall and not a revenue neutral shift between various taxes. In his view, there is no economic reason why tariffs should be any better or any worse than the income tax, both leaving people with less money to accumulate private wealth and capital. It is obvious that the US would benefit a lot from downsizing its bloated budget and cutting the massive budget deficits, as argued by McMaken.

All taxes have a negative impact on disposable income and economic growth, but various modes of taxation have different immediate impacts on income redistribution and people’s incentives to work, save, and invest.

US Taxation is Skewed Towards Taxing Personal Income and Real Estate Wealth

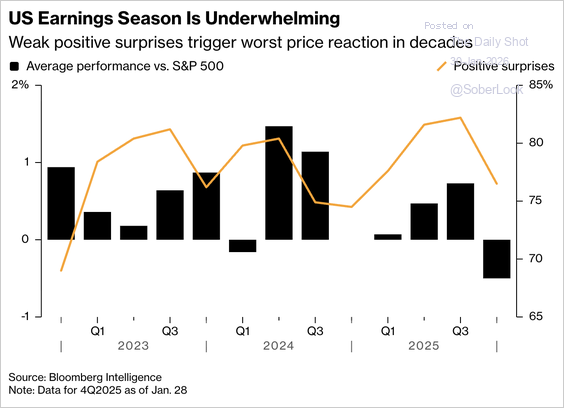

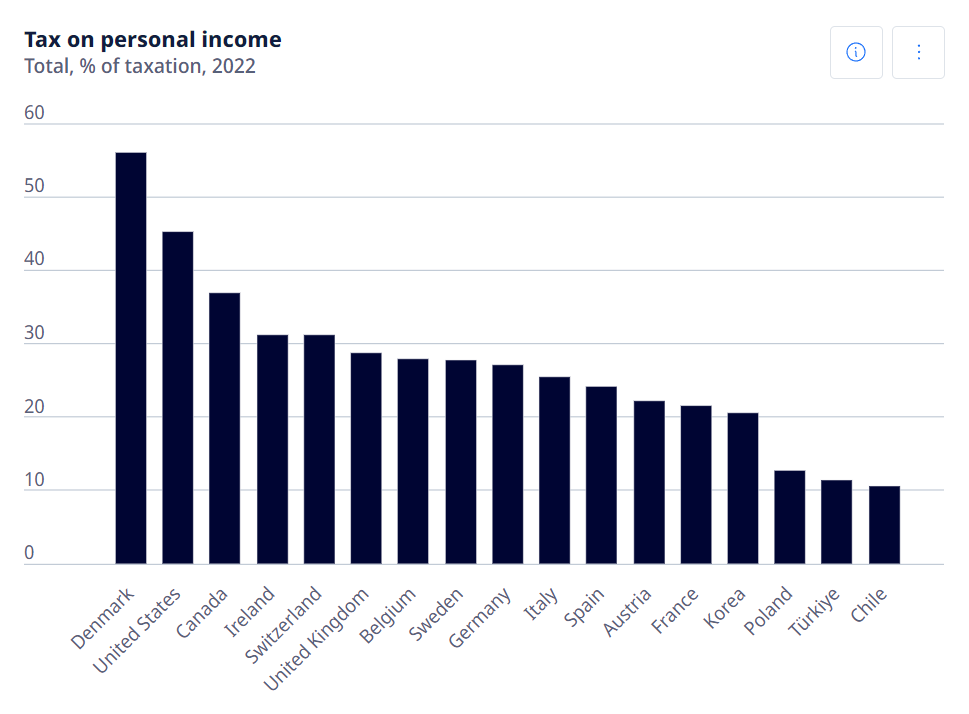

Far from being a fiscal paradise, the US still compares favorably to the majority of high income OECD countries in terms of the overall tax burden. In 2022, the US collected less than 28 percent of GDP in tax revenues relative to an OECD average of 34 percent of GDP. Tax collection in European countries is often very high at around 40 percent of GDP or more. But, despite a relatively lighter tax burden, the US economic productivity is hampered by a much heavier reliance on direct taxes, such as income, corporate and property taxes. If the US taxes somewhat less corporate profits than the average OECD countries – also thanks to Trump’s tax cuts, it is well ahead in terms of taxing personal income and property taxes. At about 45 percent of total tax revenues, the share of income tax collected by the US government is more than double the OECD average of 22 percent (Graph 1). Revenues from property taxation are also about twice as large in the US (11 percent of total taxation) than in other OECD countries.

Graph 1: Taxation of Personal Income and Capital Gains by OECD Member States

Source: OECD Data [ OECD ]

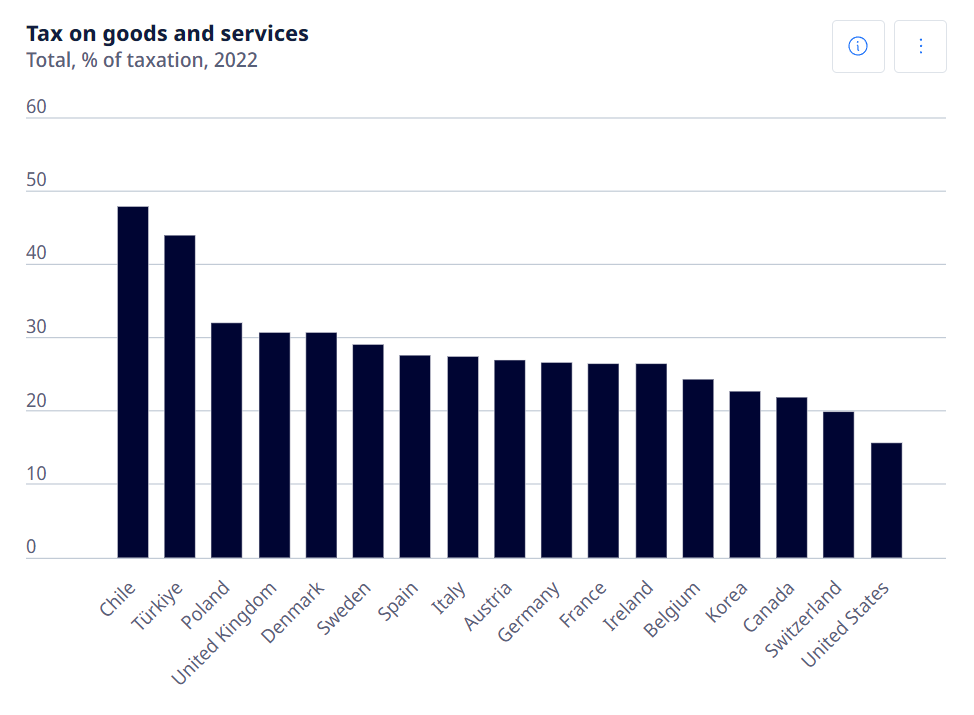

At the same time, only about 15% of collected revenues in the US, relative to an OECD average of 31 percent, come from taxes on goods and services, such as general sales taxes, VAT, excises and tariffs on foreign trade (Graph 2). In this tax category, the US is the last among OECD members.

Graph 2: Taxation of Goods and Services by OECD Member States

Source: OECD Data [ OECD ]

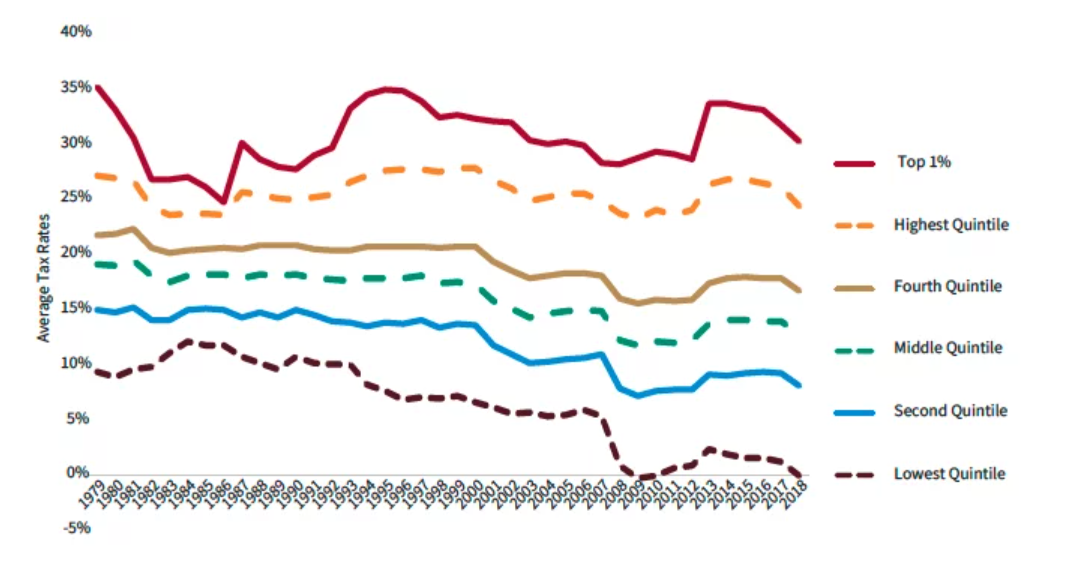

The US government manages to collect such a large share of revenues from personal income tax by running a steep progressive taxation system. In 2021, the top 50 percent of all taxpayers paid almost 98 percent of all federal individual income taxes, according to Tax Foundation. The average income tax rate was 14.9 percent, but the top 1 percent of taxpayers paid a 25.9 percent average rate (accounting for around 45 percent of revenues), nearly eight times higher than the 3.3 percent average rate paid by the bottom half of taxpayers. Incomes and taxes paid by high-income groups were also boosted by capital gains realizations exceeding USD 2 trillion. In 2018, households in the lowest income quantile paid almost no federal income tax on average, down from about 12 percent in the 1980s (Graph 3).

Graph 3: Average Federal Tax Rates for All Households, by Household Income Quintile, 1979-2018

Source: SIEPR [ Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research (SIEPR) ]

According to Ludwig von Mises, taxes should be not only small, but also “neutral” relative to the operation of the market in the absence of taxation. In practice, no tax can be truly neutral, because inequality of income and wealth are unavoidable and necessary features of the changing market economy. In any case, modern governments are not looking for “neutral” taxation at all, but pursue “just” taxation, targeting the wealthy.

Hence, the majority of modern governments go for “progressive” taxation, which in Mises’s view is nothing but a veiled expropriation of successful entrepreneurs and capitalists.

Nowadays progressive taxation seems to hurt most the middle-class, thus reducing economic and social dynamism. In general, the very rich have more means to protect their wealth by using tax loopholes and convoluted financial engineering schemes, whereas rapid capital accumulation by successful newcomer entrepreneurs is held back by very high tax rates. For example, top marginal tax wedges of 85% in Austria and 93% in France are collected on annual gross wages starting at about USD 41,000 in the former and USD 72,000 in the latter, corresponding actually to low- or middle-class incomes. The fact that countries with very low income inequality, such as Sweden, the Netherlands and Germany are leading the rankings of wealth inequality in Europe, clearly shows that economic dynamism suffers under generous welfare states.

The Problem with “Replacing” Income Taxes

Critics of Trump’s proposal have estimated that tariffs on imports would need to be set at about 70% to generate the same amount of revenue collected by the individual income tax. This is much higher than tariff increases of up to 20 percent on all imported goods and 60 percent on Chinese imports, proposed by Trump during the campaign. Critics believe that a tariff increase of around 70 percent would not be feasible, because it would significantly raise import prices and slash US foreign trade, including exports. Domestic consumers would bear the brunt of the tax hike while tariff revenues would decline in line with imports.

Criticism is most likely justified. Mises is also a vocal critic of protectionism which only benefits some domestic producers and for a limited period of time. In the long-run, the protected sectors attract new entrepreneurs, eliminating the specific gains of incumbents. If all domestic branches are protected to the same extent, everybody loses as a consumer as much as he gains as a producer. Moreover, everyone loses through a general drop in labor productivity as tariffs can induce big distortions in the structure of production and shift production to less competitive locations, unravelling the international division of labor. Exporters can also be negatively impacted by tariffs on imports of intermediate inputs and a general drop in external demand as trading partner countries see their foreign currency proceeds from exports dwindle.

Full story here Are you the author? Previous post See more for Next postTags: Featured,newsletter