In 2024 the Australian senate is establishing an inquiry into Coles and Woolworths, the two biggest grocery retailers in the country. These two retailers hold a market share of two-thirds of the retail grocery market in Australia.

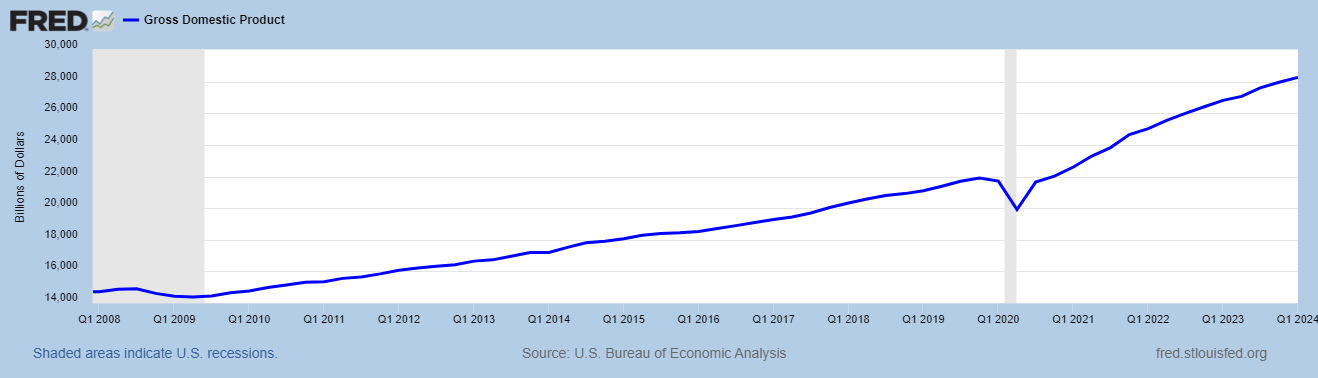

This follows sharp rises in government spending, inflation, consumer prices, and lending rates following the Covid crisis. Instead of addressing inflation-fueled spending, governments have chosen grocery retailers as the bad guy to blame for the increased cost of living.

Australian governments have been hampering the economy from multiple directions over recent years: either through the federal and state parliaments, or the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA)—a government institution. The latter fueled inflation by printing money used to buy new debt. Governments also made the Australian economy less productive through restrictions and handouts.

The government manufactured cost of living crisis

The RBA—like many of its peers around the world—significantly lowered interest rates, then printed money leading up to and during the Covid crisis. Like those other economies Australia also experienced a sharp rise in consumer prices.

During the past decade the RBA lowered interest rates from their pre-great recession high of 7.25 percent, to historic lows at or below 2.5 percent. In 2020 the RBA further lowered rates to 0.1 percent where they remained throughout the Covid crisis.

In parallel to rate decreases, a program of quantitative easing began in November 2020, running through to February 2022. Over that time the RBA purchased AUD 281 billion in government bonds, an amount just over 10 percent of Australia’s current GDP.

The purchase of bonds helped all governments throughout Australia run budget deficits. The federal government added AUD 360.5 billion of debt over the Covid period, with the RBA by far the government’s largest creditor.

Meanwhile state governments also have ballooning debt levels. Government debt for Australian states and territories is currently at about AUD 550 billion and expected to continue to grow at AUD 50 billion per year, matching the growth during Covid.

Unfortunately this policy of debt-fueled overspending was entirely bi-partisan. It took place under administrations from both two main political parties at the national and lower levels of government.

Restrictions in Australia were harsh and draconian, including the state of Victoria which saw the toughest restrictions anywhere in the western world and second only to communist China. This severely hampered economic activity. Incomes and consumer demand decreased or disappeared as whole sectors of the economy were shut down.

Employer’s costs also increased when wages needed to compete with Covid related handouts from the federal government.

Debt burdened households

Australian households are highly leveraged and addicted to mortgage debt. About one third of mortgage holders are at risk of mortgage stress thanks to these recent increases in rates and the cost of living. This problem grew sharply during Covid thanks to loose monetary policy. The period saw a sharp rise in mortgage debt as consumers entered the market under a regime of money printing and 0 percent interest rates.

It is in this environment of increasing interest rates, highly leveraged households forced to service increasingly more expensive debts, and several years of struggle in many sectors of the economy, that consumer prices for groceries have experienced sharp increases.

All households buy groceries. Their increased cost is therefore universally unpopular. If not seen as responsible for the increased cost of living, the current prime minister, Anthony Albanese, is under political pressure to address it.

More expensive production increases consumer prices

Increases in prices are the mechanism by which information about the disruption to the economy, caused by these interventions, moves through the economy. Disruptions and cost increases in one area result in price increases further down the supply chain.

As the last step in the supply chain the grocery retailer is the actor offering the final retail prices to the consumer. They could be considered the messenger delivering the retail price—affected by events throughout the supply chain—down to the retail client.

Government attacks retailers

The Australian government has decided to blame the messenger. Multiple enquiries will target the two main grocery retailers. The federal inquiry described above is accompanied by a state-level inquiry from the Queensland parliament as well as an inquiry from the ACCC, the federal government regulator tasked with regulating competition between businesses.

Grocery retailers have the difficult position of selling to the Australian community. It is in their stores that consumers see the increased prices that resulted from the money printing, debt binge, restrictions, and handouts at multiple levels of government over many years. Without an appreciation of the economic actions that led prices to change, consumers might think that retailers became slightly greedier and arbitrarily increased prices.

Governments attracted considerable scrutiny during the period in 2022 and 2023 that saw regular increases in borrowing rates and the acceleration of consumer prices. Regular monthly interest rate rises were particularly embarrassing and served as a constant reminder to the public of the deteriorating economy.

Accountability sits outside of the usual behaviour of elected politicians and unelected bureaucrats. Being seen as responsible for the current economic problems would be politically devastating for any government. Shifting blame to retailers is convenient and unfortunately is likely to be effective.

Politicization of the RBA

In the wake of this politically awkward period the government learnt some important lessons. Unfortunately, these were not a policy of fiscal responsibility and a respect for individual liberty. Rather, the lesson was that an independent RBA, with regular policy meetings that resulted in interest rate rises was a nasty source of political embarrassment for the government. It was a regular reminder to the electorate of the increased cost of living and eroding purchasing power of the currency in which their wages were paid.

The government went about solving this by holding a review of the RBA, leading to policy changes for the reserve bank. The outcomes were:

Essentially this better served the political interests of the government of the day: fewer embarrassing reminders of their fiscal irresponsibility and more short-term inflation over the longer-term health of the economy.

This case shows the importance of—and unfortunately scant—economic literacy in the electorate. Redirecting blame to retailers only works when an electorate is not paying attention to, nor understands the economic actions of governments that preceded the current difficult economic conditions.

Money printing, low interest rates, and cheaper mortgages are popular. This popularity is often amongst an electorate whose fixed wages and salary incomes decrease in value as a direct result of these policies.

Full story here Are you the author? Previous post See more for Next postTags: Featured,newsletter