What contributes to the wealth of a nation? Gross national income (GNI) and gross domestic product (GDP) are two well-known measures of a country’s economic growth. One measures the earnings of a country, and the other measures the value of the final goods produced by the country. What drives these measures in the twenty-first century? We are now witnessing a pivotal technological divide among countries in their ability to invest in and deploy artificial intelligence (AI) and robotics in the means of production—a divide that is creating AI haves and have-nots.

Individual energy per capita will be enormous as technological change—like AI, automation, and robotics—unleashes the ability of entrepreneurs to build apps and customize workspaces that accompany AI-augmented work partnerships between man and machine. Some economists think they can calculate a nation’s GDP, wealth, and overall human happiness by the size and consumption of Big Macs within its borders. I doubt it. In this epoch, we will measure the wealth of a country not by the size and consumption of Big Mac and fries, but rather by a more relevant measure—robotics and AI deployment in the production of products and services.

Let us walk down memory lane: centuries ago, Adam Smith’s book The Wealth of Nations proposed a principle of free trade and commerce, and investigated how nations prosper via market exchange. Moving forward to the end of the twentieth century, the esteemed economic historian Alfred Chandler, in the 1997 book Big Business and the Wealth of Nations, proposed that the wealth of a nation was big business, managerial hierarchy, knowledge-intensive industries, and the rapid corporate strategies of unrelated diversification. Almost thirty years later, we are witnessing the power of machine learning and robotic production the likes of which Adam Smith and Alfred Chandler could never have imagined—and integrating these tools with human entrepreneurship.

Despite all the naysayers and doomsayers, widespread data suggests the opposite of AI and robotics taking human jobs; instead, AI-related jobs and skills are opening up employment, markets, and industries. According to Stanford University’s Artificial Intelligence Index Report 2023, projections point toward AI’s strength capacity and employability for humans as a growth area: AI job growth adds to the productivity of countries—and sorry, not based on the size and consumption of Big Macs!

For the casual observer, it is difficult to discern how AI and robotics private investment might lead to the wealth of a nation. For this, it would benefit us to use the words of Frédéric Bastiat—the seen and the unseen. What is seen in a wealthy country is the consumption of goods (Big Macs) and the manufacturers’ production equipment (burger and fry production). However, what goes unseen is the technological deployment and the value chain to produce buns, fries, cups, and equipment for in-store and app-enabled orders.

What else is seen? We see vehicles, food in the grocery stores, smartphones, and other valuable gadgets. We see, as consumers, various goods for purchase and the lightning-fast speed of consumer goods delivered to our doorsteps, app-enabled services to protect our homes, or even smartphone laundry applications that allow us to start and stop our appliances when we are away from home. These modern examples of AI support are irrefutable and are exemplars of how AI technology has enhanced our happiness; the way we interface in the marketplace is dependent on AI to some extent.

However, what is unseen is the AI technology used to produce the everyday goods we prize the most. AI and robotics are an economic backbone that make all this economic expansion happen behind the scenes. Disdaining AI is akin to liking the taste of sausage but being repulsed by the way it is made. In other words, consumption (which we all do) begets a better and stronger demand for the mechanism to produce more in different ways than have traditionally been used.

Think about this: What explains how I can get what I want and how you can get what you want in the marketplace? In other words, what helps us produce and trade with one another? A central planning board? No. The wealth of a nation is determined not only by its productive powers and its productive entrepreneurs but also by its productive citizens who produce for their fellow man via the use of modern technology.

Take, for example, Adam Smith’s pin factory. Smith writes in The Wealth of Nations that

...a workman not educated to this business . . . nor acquainted with the use of machinery employed in it . . . could scarce, perhaps, with his utmost industry, make one pin in a day, certainly could not make twenty. . . . I have seen a small factory of this kind where ten men only were employed, and where some of them consequently performed two or three distinct operations. But though they were very poor, and therefore indifferently accommodated with the necessary machinery, they could, when they exerted themselves, make among them about twelve pounds of pins in a day.

How are pins made today? By ten workers using rudimentary machines? Unlikely. Today, people searching for pins can buy as many pins as they might want at any store. And I am almost certain that the mass availability of pins exists because today’s pin factories use robotic machines and AI technology to get pins of various colors and designs to consumers in various locations. Without robotics and intelligent AI software and services, would the production of pins be more limited?

In this regard, Alfred Chandler writes, “As was true of the earlier capital-intensive, scale-dependent technologies, unless organizational capabilities were developed and maintained, the critical learning base often disintegrated. Once lost, it was rarely regained. This was probably even more true in the knowledge-intensive, scope-dependent industries of the second half of the [twentieth] century than it was for the capital-intensive and scale-dependent industries of the first period of the modern economic growth.” Chandler continues, “Learned product-specific organizational capabilities had to be maintained and enhanced. Once capabilities disintegrated, competitive power rarely returned.”

What happens when all is lost: learning, knowledge, capabilities, entrepreneurship? Chandler’s point is that if a country shies away from AI and robotics in the production process, it will lose the know-how and the how-to in production over time, thus lowering the country’s wealth. Countries that disregard the power of private investment in AI and robotics will be left behind. It becomes apparent in the AI Index Report 2023 that jobs related to the fields supporting and investing in AI, not the size and consumption of Big Macs, will measure future wealth creation. Although Big Macs are tasty, it is hard to believe they measure the economic productivity of a wealthy nation.

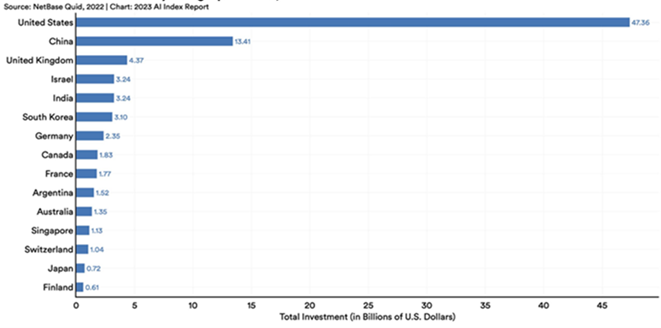

Private investment in the production and deployment of AI and robotics contributes to a country’s wealth. The AI Index Report 2023 reports, “In 2022 the amount of private investment in AI was 18 times greater than it was in 2013.” Figure 1 shows that this investment varies greatly by country. The private sector is wresting AI from the grip of the elite, which will not be an easy task. Given the investment in AI, opening new markets (domestic and international) will promote a nation’s prosperity. AI and automation will not cause technological unemployment.

Figure 1: Newly Funded AI Companies by Geographic Area, 2022

Source: Artificial Intelligence Index Report 2023 (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence, 2023), fig. 4.2.16.

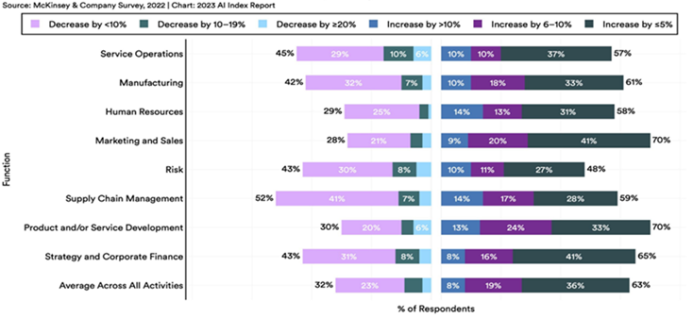

While the intelligentsia and the elite may turn up their noses at Adam Smith, Alfred Chandler, and Murray Rothbard, the harsh reality is that the investment, use, and deployment of AI increase everyone’s freedom, which contributes to the productivity of society. Figure 2 shows that adoption of AI leads to decreased costs and increased revenues across all sectors.

Figure 2: Cost Decrease and Revenue Increase from AI Adoption by Function, 2021

Source: Artificial Intelligence Index Report 2023, fig. 4.3.7.

It is a fact that the costs of production decrease when technology is used. Again, imagine Adam Smith’s pin factory’s production power if they had access to automation, AI, and robotics! We can see that integrating AI, human energy, and robotics in the production and consumption process grows a country’s economy.

Despite what the bogeymen say about the downsides of AI and robotics, the benefits for the creation of wealth of investing in AI, robotics, and automation are visible in the things we consume. However, if a nation does not pursue investment in AI competencies and capabilities in the means of production, that nation will become marginalized—left behind in advancements oriented around global trade and domestic opportunities. Therefore, the wealth of nations will come down to which countries invest in the technological means to integrate human skills with AI, robotics, and automated production.

Full story here Are you the author? Previous post See more for Next postTags: Featured,newsletter