“Experts” at the Federal Reserve and other central banks proudly broadcast the potential “financial inclusion” that could be achieved with a central bank digital currency (CBDC). In the Fed’s main CBDC paper, “Money and Payments: The U.S. Dollar in the Age of Digital Transformation,” they make it clear: “Promoting financial inclusion—particularly for economically vulnerable households and communities—is a high priority for the Federal Reserve . . . a CBDC could reduce common barriers to financial inclusion.”

The term has a ring to it that signals support for progressive goals. “Inclusion” is part of the Orwellian trio of terms “diversity, inclusion, and equity,” which, as Dr. Michael Rectenwald writes, means “surveillance, punishment of the ‘privileged,’ sacrifice of national citizens to global interests, and the labeling as ‘dangerous’ and marking for (virtual) elimination those supposed members or leaders of ‘hate groups’ who oppose such measures.” The central banks’ use of “financial inclusion” involves the same reversal of meanings.

Financial Inclusion and Unbanked Households

Consider that a retail CBDC would be like having a bank account with the Federal Reserve, even if it is intermediated by another bank. There is a lot of guesswork about how a CBDC will be implemented, but some say that it will not just be like having a bank account with the Fed, but that it could be exactly that.

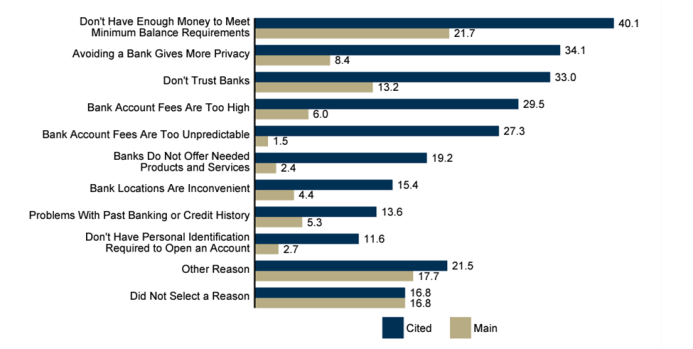

Either way, if a CBDC were genuinely aimed at financial inclusion, it would offer something to those who have chosen to forgo a bank account entirely. This “unbanked” population constitutes about 5.4 percent of US households according to a 2021 Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) survey. The survey asked each household why they do not have a bank account, and the responses indicate that minimum balance requirements, privacy, trust, and fees are the most significant factors.

Figure 1: Unbanked households’ reasons for not having a bank account, 2021 (percent)

Source: FDIC, 2021 FDIC National Survey of Unbanked and Underbanked Households (FDIC, 2022), fig. ES.3.

The critical question, then, is this: what does a CBDC offer these households that physical cash and other nonbank financial services (e.g., check cashing, money orders, prepaid cards) do not?

Privacy (or Lack Thereof)

A CBDC undermines privacy. Whatever a central bank might say about privacy protection with a CBDC can be safely dismissed. The Fed paper, for example, says, “Protecting consumer privacy is critical. Any CBDC would need to strike an appropriate balance, however, between safeguarding the privacy rights of consumers and affording the transparency necessary to deter criminal activity.” We should not conflate the characteristics of a CBDC with those of cryptocurrencies in general, which offer anonymity and pseudonymity to their users.

Consider how the IRS recently pried open PayPal, Venmo, and Cash App accounts with transactions over $600. Consider also that the Supreme Court just ruled that the IRS can investigate your bank accounts without notification in some circumstances, including if you are a friend, family member, or associate of someone who owes the IRS.

Beyond taxes, banks also willingly hand over personal information (even without a warrant or formal request) to the FBI. This data, which includes previous firearm purchases, belongs to people who show up at the wrong protest or who were merely in the vicinity as the data is collected based on transactions within a specific geographic area.

The lack of privacy with bank accounts certainly contributes to the distrust people have for banks, as noted in the survey. This shows that “financial inclusion” is a mere buzzword as there is nothing about a CBDC that would gain the trust of unbanked households, who are not excluded from the banking system but actively avoid it.

Fees and Negative Interest Rates

According to the survey, fees are another commonly cited reason for being unbanked. People avoid banks because the fees are steep and unpredictable.

Although there is no certainty regarding how a CBDC would operate, many see that it could finally offer the holy grail of monetary policy: the ability to impose negative interest rates. In effect, this would be a fee for holding a CBDC.

After the 2008 crash, the Fed reached the “zero lower bound” for nominal interest rates. They were unable to stimulate more spending through their interest rate targeting approach. While there were a few outlandish ideas about imposing a negative interest rate on cash, like the idea of Greg Mankiw’s student to remove the legal tender status of all currency with a serial number ending in a randomly selected digit, it is just too difficult to impose a fee on the cash in your wallet or safe.

With a digital currency, it becomes effortless, especially if the use of physical cash is significantly diminished or even eliminated altogether. The monetary policy authorities would simply press a button and deduct a certain amount of CBDC from everyone’s accounts. Think of the spending they would encourage if everybody knew their unspent money would be subject to such a penalty!

Conclusion

The “financial inclusion” rhetoric in central bank papers and speeches on CBDCs is laughable. Presently, people avoid banks because they distrust banks, value privacy, and despise fees. A CBDC wouldn’t help with any of these concerns. Instead of promoting inclusion, a CBDC would become the ultimate tool for financial intrusion and control.

The tyrannical potential is not a secret, even for the army of technocrats pushing for CBDCs. At a recent World Economic Forum event in China, Eswar Prasad matter-of-factly brandished the inevitable weaponization of CBDCs:

And one final note that I’ll make is that if you think about the benefits of digital money, there are huge potential gains. It’s not just about digital forms of physical currency—you can have programmability, units of central bank currency with expiry dates. You could have, as I argue in my book, a potentially better, or some people might say, darker world, where the government decides that units of central bank money can be used to purchase some things, but not other things that it deems less desirable, like, say, ammunition or drugs or pornography or something of the sort. And that is very powerful in terms of the use of a CBDC.

Of course, any moral qualms we have regarding the items he listed are irrelevant. It is clear that the state will use CBDCs to push us toward anything the state favors and away from anything the state doesn’t. Programmable money means programmable citizens.

Full story here Are you the author? Previous post See more for Next postTags: Featured,newsletter