The energy crisis is causing electricity prices to soar across Europe, including in Switzerland. But the impact on the country is very unequal because of specific characteristics of its market.

The sharp rise in electricity prices has delivered a heavy blow to the European market, which has been fully liberalised since 2007. States are being forced to delve deep into their coffers to support households and businesses. Voices questioning the wisdom of fully opening the market to competition, or at least the way it was implemented, are getting louder.

In the heart of Europe, Switzerland is also suffering from the energy crisis, but a distinctive characteristic of its market is that it is only partially liberalised. Here we explain the background.

How does the Swiss electricity market work?

Since the 1990s, electricity suppliers and network operators have gradually been privatised. But in 90% of cases, the main shareholders are still the public authorities. In 2009, the Swiss market was partially liberalised: companies whose consumption exceeds 100,000 kWh per year can freely choose their supplier. However, they represent only 0.8% of all grid users.

Households and smaller companies are so-called “captive customers”, obliged to consume electricity from their local supplier. This means that prices can vary greatly from one municipality to another: in 2022, the inhabitants of the city of Basel paid 28 cents per kWh, while the population of the municipality of Simplon in Valais paid only 11 cents.

Who are the main electricity players in Switzerland?

There are around 630 distribution network operators in Switzerland, 70% of which do not produce electricity. These are often municipalities, which have to guarantee supply in a clearly defined area. A handful of companies have expanded on a national and even an international level. The Swiss government has identified three systemically important electricity suppliers whose failure could affect the supply of the entire country: Axpo, Alpiq and BKW.

Swissgrid is also a major player in the Swiss market, as it manages the entire high-voltage transmission system and ensures the exchange of electricity with European countries. The company is owned by the major Swiss energy companies.

How are electricity prices set in Switzerland?

The electricity tariff for captive customers is a combination of the energy price, the transmission price and various taxes and charges. The bill varies from one municipality to another because of the amount of taxes levied locally, but also because of the supply strategy of the local supplier. Some companies produce a large proportion of their electricity themselves, while others buy it; some have already concluded contracts several years in advance, while others procure electricity on a short-term basis. These strategies have a direct impact on consumers’ bills, depending on market fluctuations.

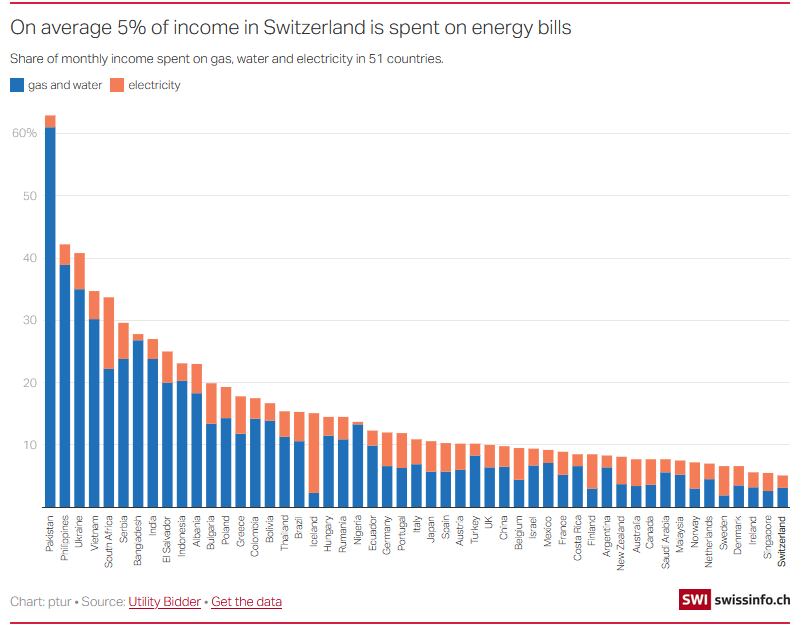

The current law guarantees captive customers access to the network, the desired quantity of energy and “fair tariffs”. In 2021, the average price in Switzerland was 18.5 Swiss cents per kWh, while the average in EU countries was 22 euro cents.

Even if captive customers do not have the option of switching providers, the companies are entitled to raise prices if the increase is justified. Each year, the 630 network operators must submit their tariffs to the Federal Electricity Commission (ElCom). The commission can prohibit unjustified price increases or reduce excessive amounts retroactively.

What are the consequences for Switzerland of the international rise in electricity prices?The country’s production, mainly from hydroelectric power stations, more than covers its requirements during the summer months. In winter, however, Switzerland has to import around 40% of its electricity. Suppliers have to buy energy on the European market, where prices are at record levels. As a result, Swiss consumers will see their bills rise in 2023. ElCom expects an average increase of 27%. However, the situation varies from company to company. A grid operator like BKW in Bern, which produces a large part of its own electricity, is not affected by international price fluctuations. In 2023, its customers will have to pay 25.5 cents per kWh, compared with 25.2 cents in 2022. Romande Energie, on the other hand, which only produces 40% of the electricity in its network, will raise tariffs from 21.2 cents in 2022 to 32.2 cents in 2023. The energy crisis is also affecting large electricity suppliers such as Axpo and Alpiq, which are struggling to find the cash needed to pay for guarantees for their future contracts. Axpo asked the Swiss government for support and obtained a loan of CHF4 billion. The same approach is being taken throughout Europe: Germany, Austria and the Scandinavian countries have just released several billion francs to provide liquidity to their energy companies. |

How does Switzerland fit into the European electricity market?

From a technical point of view, the Swiss electricity network is an essential part of the European network. With its 41 cross-border high-voltage lines, it guarantees transfers from one country to another. Switzerland depends on these connections to ensure its supply: it can export electricity when production exceeds requirements and import it when domestic output is insufficient.

But since Switzerland is not a member of the European Union and has not fully liberalised its market, relations are complicated. Bilateral energy negotiations were halted last year when the Swiss government decided to end discussions on the framework agreement with the EU. Pending a possible resumption of the dialogue, Swissgrid has taken over and is conducting more technical negotiations with the European grid operators.

Why is the Swiss market not fully liberalised?

The Swiss government wanted to follow the European trend, but was stopped by the people in 2002: 52.6% of voters refused to liberalise the Swiss market. In 2017, however, the electorate approved a new energy law that provides for the gradual closure of all nuclear power plants in the country.

European market developments and Switzerland’s desire to phase out nuclear power have prompted the government to draft a new electricity supply law. This law provides for the complete liberalisation of the market and the rapid development of renewable energies in Switzerland. This text will soon be examined by parliament. The debate is likely to be particularly impassioned in the current context.

Adapted from French by Catherine Hickley

Full story here Are you the author? Previous post See more for Next postTags: Environment,Featured,newsletter