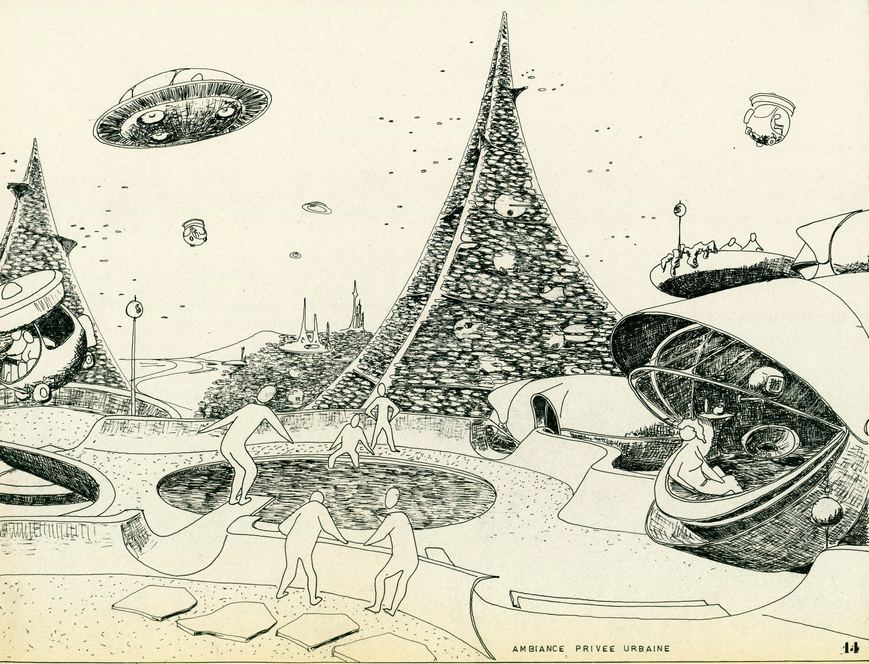

Futuristic architecture sketches from Pascal Häusermann, 1970. Competition in Cannes, private urban atmosphere. Collection Frac Centre-Val de Loire / Donation Pascal Häusermann

Swiss architects were swept up in the movement to build bubble houses out of concrete and plastic in the 1960s. While the bubble movement burst decades ago, many of the original structures are still standing to this day.

Need more space? Why not just build an extra room on the side of your flat? Fifty years ago, a Geneva architect turned this dream of many tenants into reality in a radical way. In the late 1970s, 23-year-old Marcel Lachat and his wife were expecting a child, but there weren’t any bigger flats available on the market. Lachat came up with a way to solve the problem: build an extension.

With help from friends, he hung a bubble-shaped polyester “room” onto the façade of his rental flat. This gave him the extra space for a cosy children’s bedroom. What Lachat didn’t know then is that these ten square metres would capture the attention of Swiss media, as an “anarchic” extension. The “bubble” had to be torn down shortly afterwards.

The uproar was more focused on Lachat’s audacity to build an extension onto his rental flat than it was about its bubble shape. In the 1960s, experiments with bubble architecture were flourishing internationally.

Revolution in form

In the 1940s, the American architect Wallace Neff began building houses by coating neoprene balls with powder and covering them with sprayed concrete. This spread across the globe, with some 1,500 bubble houses built according to his design still standing in Senegal. He struggled, however, to gain a foothold in the domestic market. The bubble house, despite its cheap and quick construction method, was not attractive enough for western industrial nations. Some practical questions arose – where does the furniture go when you have round walls?

In the 1960s, the idea acquired a rebellious spin. The strict geometry of modernist town planning and its functionalism seemed increasingly restrictive. Urban construction for the baby-boomer generation was focused on efficiency, and not on the individual.

This was an era where private life was declared political – single-family homes and holiday homes became places to express oneself. The architecture critic Michel Ragon said at the time that thanks to plastic and spray concrete, architecture could at last compete with structures such as skeletons, spiderwebs, drops of water and soap bubbles and could rebel “against the tyrannical formula of six walls”. Many designs of the era were attempts to literally move away from the straight lines of modern architecture with organic and biomorphic shapes.

Neff’s bubble houses suddenly appeared to be following in the tradition of Rudolf Steiner’s Goetheanum, the architectonic utopias of Hermann Finsterlin or visions like Buckminster Fuller’s futuristic cathedral architecture. The form of the bubble, above all, conveyed the image of a very unique world tailored to a special individual.

At the same time, it also fit perfectly into the 1960s as a symbol for dreams and illusions that threaten to burst.

Anarchic interventions

Lachat’s Geneva bubble not only illustrates how necessity is the mother of invention, it also follows a radical concept of do-it-yourself architecture. Lachat had read the French architect Jean-Louis Chanéac’s “Manifesto for Insurrectionary Architecture”. Chanéac’s vision went beyond family homes with radical chic to anarchistic interventions.

The dream is architecture without architects. Claude Costy said in 1981: “The industrial age led to the disappearance of creating one’s own home and its traditions. (…) In our ecological age, the possibility of building one’s own home is emerging again”.

Claude Costy and her husband Pascal Häusermann had by then already made their names as architects with an array of bubble-like buildings. In 1959, Pascal Häusermann built his first little house near Geneva on rocky ground. The basic structure was a bubble made of sprayed concrete. In 1967, he and his wife built the “L’eau de Vive” settlement in Raon-l’Étape, France, which can still be visited today. It took a shape not unlike the animated figures in Barbapapa, and was promoted in 2000 as the prototype for a hotel.

Häusermann, Costy and Chanéac planned to build settlements out of plastic “Domobiles” that could be freely reassembled so that living space could be continuously reorganised. People would not have to look for a new flat when their living arrangements changed. The flat itself could adapt.

Swiss bubbles in Iran

The oil shock of 1973 metaphorically burst the architectural bubbles. That was partly because the bubbles, with minimal insulation, suddenly appeared to be an energy extravagance. Moreover, at the end of a period of prosperity, their enthusiasm for form suddenly looked like dried-out flowers in ageing hippies’ hair.

Two people who kept faith in bubble architecture are the Swiss architect Justus Dahinden, a member of the avant-garde “Groupe International d’Architecture Prospective”, and the engineer Heinz Isler, who had experimented with elaborate concrete dish constructions since the 1950s.

In the midst of the biggest economic slump since 1945, the two set the goal of building a town in northern Iran for 30,000 people – consisting of bubble houses. A first unit was built in Amirabad in 1976. But the Islamic revolution prevented the construction of the bubble city of Moghan.

While Dahinden turned to new projects, Isler, the engineer, tried to transform the concept into a business idea. He founded Bubble Systems AG and tried to sell the houses in Switzerland. He had little success.

If you stray into the woods near Burgdorf in canton Bern, you can find weather-beaten concrete spheres that look like the lonely building in Iran. But while its twin in Iran seems to resemble the traditional domes of the region, Isler’s bubble house in Lyssachschachen, weathered and covered in moss, still recalls the burst future of the bubbles of concrete and plastic.

Literature

- Raphaëlle Saint-Pierre: Maisons-bulles. Architectures organiques des année 1960 et 1970. Patrimoine 2015

- Leïla El-Wakil: Pascal Häusermann, une architecture libertaire pour délivrer le monde (Tracés 5/2017)

- Matthias Beckh/Giulia Boller: Building with air: Heinz Isler’s bubble houses (Conference of the Construction History Society 2019)

Tags: Culture,Featured,newsletter