UN economist Ian Richards argues that Swiss voters’ fears of a proposal for an e-ID may be swept away as more countries see the benefits of digitising documents, including vaccine passports.

A week ago the Swiss public voted overwhelmingly to reject a digital identity scheme that would have given each Swiss citizen and resident an official login and password to open bank accounts, vote, or buy train tickets and ski passes online.

The login would be certified, meaning that the holder’s identity would have been checked beforehand. Any website would then be able to accept the login at face value.

Among the benefits of what was known as e-ID, Swiss residents would no longer need to send sensitive documents in the mail (suspicions were raised two years ago about the reliability of postal voting), remember multiple passwords or rely on password managers such as Google or Facebook. It would also provide legal regulation to online identities, addressing long-standing privacy and security concerns.

The idea of a digital identity scheme is not new. It is commonly used in the Scandinavian countries and Estonia.

For its system, Bern decided that the login would not be issued by the government but by licensed private companies that would be able to access the central police database to do their checks.

Swiss justice minister Karin Keller-Sutter justified the involvement of the private sector, saying that the government itself did not have the technology nor wherewithal to implement such a scheme.

This provoked a backlash among privacy campaigners. Last year they collected 65,000 signatures and triggered a national referendum.

Their main argument was that the issuing of identity documents should be confined to the state, even though Keller-Sutter was at pains to point out that the e-ID was not intended to replace identity cards or passports. They also raised concerns about companies profiting from using citizens’ private data. Voters might find their identity being handled by local supermarket chain Migros, NGO bugbear and commodity trading firm Glencore, or worse, Facebook itself. Many political parties agreed with them.

Keller-Sutter originally said there was no Plan B to private sector involvement. However, in the aftermath of the vote, she accepted to take on the concerns expressed by the no campaign.

Putting e-ID under government management creates many possibilities that were not considered in the referendum campaign, including the very digital identity cards and passports that were originally ruled out.

In Estonia, for example, the electronic identity system is linked to the national identity card, which can be used together with a card reader instead of a login, to do bank transactions, start companies, get prescriptions or prove the ownership of other documents such as a driving license. Over 98% of the population does this alreadyExternal link.

But that’s only the start.

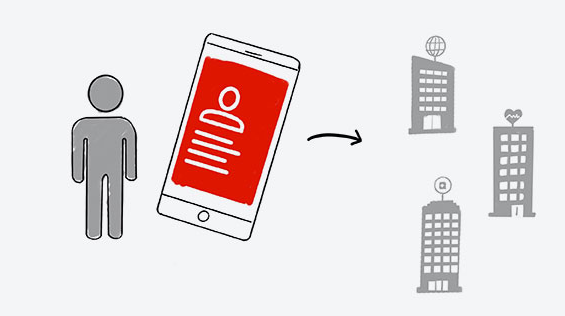

The UN Conference on Trade and Development is working with the governments of Iraq and Benin to allow digital versions of government documents to be stored on a mobile phone while being certified as authentic through blockchain technology. They could be presented to the police or other government departments without further checks being necessary. British Columbia already runs such an operationExternal link for businesses in the province.

If the Swiss government were to go beyond e-ID and allow the storage of digital passports, identity cards, driving licenses, work or residency permits, or any other document on a mobile phone, accessible through a face scan, it would make living in the country considerably more convenient.

To enter the country you would scan a QR code instead of lining up at passport control. To obtain a resident’s parking permit, you would upload your identity card and car registration to the municipality website, and pay by credit card. With no human checks required, the permit could be automatically issued within seconds. No more queues at government offices. Work permits could be renewed and companies created the same way. An e-ID login wouldn’t even be necessary.

Speeding up government procedures and liberating government officials from the mind-numbing task of checking documents all day also brings economic gains.

The McKinsey Global Institute recently reportedExternal link that “allowing incremental digitization of sensitive interactions that require high levels of trust” could add between three and 13% of GDP.

This is backed by the United Nations’ own experience in helping developing countries implement digital government systemsExternal link for company registries. In all cases these have led to an increase in companies being created, and paying taxes and social security. Women and young entrepreneurs were the main beneficiaries.

The government may have considered digital identity cards or passports too high tech or dystopian compared to the simpler e-ID login. But that could be about to change.

Over the next months the Swiss will start planning their summer holidays.

Greece, as well as other Swiss beach favourites such as Spain and Portugal have floated the idea of making digital vaccine passports a condition of entry. As things stand, these 2021 versions of the government-issued yellow cardboard certificates will most likely be managed by IATAExternal link, a private airline association, and stored on a mobile phone.

Yes, vaccine passports remain controversial. The World Health Organization says “there are still critical unknowns regarding the efficacy of vaccination in reducing transmissionExternal link” and there has been little discussion about how these will be regulated.

But if it comes down to a choice between another summer of pricey mountain resorts or freshly grilled fish at a beach-side taverna, many will likely vote with their swimming trunks, download their digital vaccine passport and travel abroad.

Holiday-makers in other countries will be doing the same, and on returning home there will likely be a rush by governments to do for passports and other documents what IATA did for vaccine certificates and what Iraq, Benin and British Columbia are doing themselves.

In six months the main criticism of e-ID might not be that it goes too far, but that it doesn’t go far enough.

Ian Richards is an economist and digital government expert at the United Nations.

The views expressed in this article are solely those of the author, and do not necessarily reflect the views of SWI swissinfo.ch.

Opinion series

SWI swissinfo.ch publishes op-ed articles by contributors writing on a wide range of topics – Swiss issues or those that impact Switzerland. The selection of articles presents a diversity of opinions designed to enrich the debate on the issues discussed. If you would like to submit an idea for an opinion piece, please e-mail [email protected].

End of insertion

Tags: Featured,Law and order,newsletter