Investors like to short bonds, even Treasuries, as much as they might stocks and their ilk. It should be no surprise that profit-maximizing speculators will seek the best risk-adjusted returns wherever and whenever they might perceive them. If one, or a whole bunch, has to first “borrow” a security the one doesn’t own in order to sell something at a high price betting the price to go down, you can likewise bet there’s someone out there in the financial landscape more than willing to let you borrow that security – for a fee.

Leverage all around.

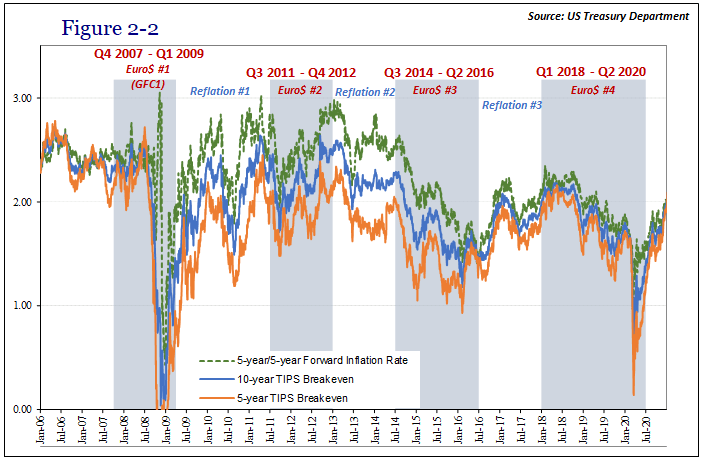

When it comes to the intersection of bonds and securities lending, money dealers may not have quite the inventory themselves but they certainly have access to any kind of instrument you could want to borrow from those who do (insurance companies and pension funds, to start with). If, as a speculator, you think inflation’s going up (or, at least, a touch less deflation) and growth prospects system-wide are improving, then your shorting sense is surely to zero in on safe and liquid assets especially if they are yielding somewhere down close to zero.

Asymmetry is the name of the game here; a minor burst of inflation following a time when deflationary pressures (not the Fed; we’ll get to what the central bank actually does in a minute) had overwhelmingly pushed government bond prices sky high would appear to offer fat, low risk-adjusted returns (because a little inflation is, many say, all but guaranteed and there’s a chance, they also say, a lot more could follow). All anyone needs to do is borrow some Treasuries and sell what they don’t actually own.

This kind of thing, however, isn’t exactly a specialist idea. Right around the time you’re thinking to short long UST’s pretty much everyone else is thinking the exact same thing; chasing the identical White Whale identified by every single internet financial news story parroting whichever Fed Chairman’s boasting about what their bank reserves will certainly do to the price environment.

While the securities lending side of the financial world can be and most often is pliable, fungible, and, at times, horrifically forgiving, there can be situations such that there are “too many” shorts. Securities dealers – or the insurance companies they borrow securities from – can become skittish themselves without notice; the dealer who let you borrow a UST yesterday at a premium you liked then today decides to up the fee and reduce your leverage (changing the risk-adjustment to your expected profit calculation).

That’s when it comes time to cover. How? Buy the thing back? Ha!

Why not borrow it from someone else?

This kind of tangled mess of heaving demand for already-borrowed securities can manifest in something called “specialness.” In repo markets, this is indicated when the repo rate for a specific security sticks out like a sore thumb – because it plummets below the general collateral rate or specific rate of specific securities in the maturity range around the one in question.

This particular instrument is now “special.”

What that means is cash lenders are willing to accept less return in order to lend cash at the same time they are borrowing this targeted special security; all that means is they aren’t really lending cash at all, both cash and collateral here in repo means something a little different than a securitized interbank loan.

The lower the repo rate on that security drops, the more special it becomes, the more there must be strong demand for it – to the point that, in some extreme situations, the special repo rate can be negative, even highly negative.

A negative special repo rate is a situation where cash lenders have become increasingly desperate to close out their problem (borrowed) position in that very instrument and have a specific obligation to deliver that exact security (rather than in general collateral repo any obligation for re-delivery is for a “similar” instrument). If there aren’t enough of it being offered by securities lenders, then cash lenders (again, who aren’t really lending cash here) will have to pay high premiums (negative repo rate: pay the counterparty borrowing cash to borrow the cash) to rent the increasingly special one.

As absurd as all this may sound, it does happen periodically in the extreme. One such instance was last March (and we’ll get to that in a minute, too). Another, the summer of 2013. In late August that year, Bloomberg reported on a particularly stark specials outbreak:

Treasury notes with maturities ranging from two to seven years have become coveted in the short-term market for borrowing and lending securities as the government auctions more of the securities this week.

Traders have been willing to pay to borrow the debt in exchange for loaning cash for the most actively traded five-, seven- and 10-year notes, with repurchase agreement rates negative. Many times traders short, or sell securities they’ve borrowed in the repo market, ahead [sic] a Treasury sale to profit if prices of the securities fall after the auction.

| Or, specific to that particular summer, when Treasury prices appear to be crashing. Thus, it would make perfect sense that collateral (borrowed instruments) would be in high demand for speculative purposes with speculators convinced (even if temporarily) of inflationary conditions ahead and sliding prices in safe assets.

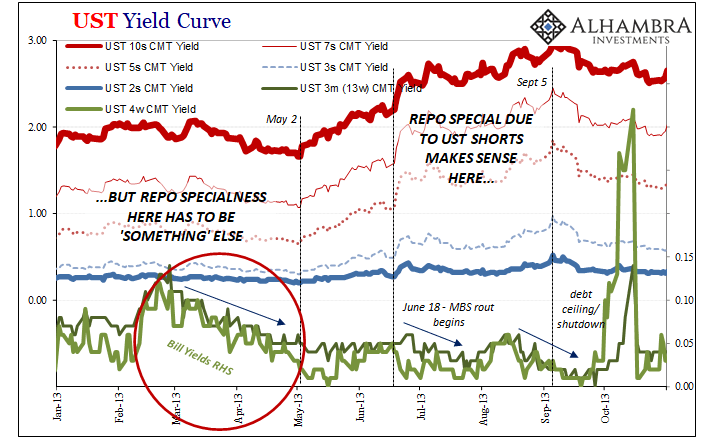

Added to that negative price pressure, there was also the so-called taper tantrum aspect which said that once the Fed stopped buying as many UST’s (and MBS) they’d leave “too many” for the market to digest, forcing bond prices down even more. The Treasury short sharks circled. But while that all seemed to make perfect sense in August 2013, even June, the specialness of UST notes and bonds in repo predated the “taper tantrum” by two and even three months. Going all the way back to February and March (see above), there was already something amiss with “too much” demand for collateral borrowing. In fact, as we discussed last year, authorities had been alarmed enough to:

And UST bond prices weren’t falling (rates rising) during those particular months before May 2013; quite the opposite. Long end yields would drop as would, importantly, those at the short end (bills). If speculators shorting notes were to blame for pre-“taper” specialness, they would have been betting on an inflation view that wasn’t yet widely shared (let alone priced) and at that time QE4 was considered to have been still “open ended.” |

UST Yield Curve, 2013 |

No. By the time taper rolled around in May, while reflation may have taken hold in notes and bonds, then afterwards boosting the short selling factor, there were already signs of something else which also takes the form of “not enough” securities available to be borrowed (or repledged). Writing in early June 2013 (under the title Repo Warning Returns; emphasis on “returns”), before the reflation had gotten very far:

Not long after, the Fed curiously stopped buying OTR notes (but that’s another if related story). In other words, what happened in the summer of 2013 was mix of two issues, the one preluding the other; increasingly confident Treasury shorts bidding reflation becoming inflation further boosted by taper, but after May and more so July and August; plus, already in effect, collateral shortage exacerbated by QE4 (and QE3 in MBS, but that’s somewhat of a different story, too) stripping notes, bonds, and bills, the “typical” post-2007 repo/eurodollar problem. The UST shorts simply contributed to the already-underlying shortage, and in a sense exposed it even further at a very inopportune moment for their reflation thesis – the source of much confusion. There was reflation in the long end pushing rates up as it looked like, in general throughout the US and the world, things were improving at the same time in other places, as well as in the same place as the shorts, collateral squeezes were indicating that it wasn’t improving in money terms and because of this the general reflation wouldn’t last very long. It didn’t. |

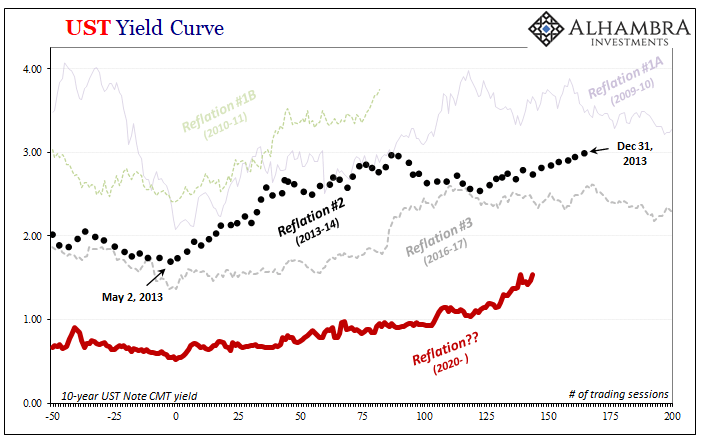

UST Yield Curve, 2013-2020 |

| Mere months later Euro$ #3 began to more heavily impose itself on the very first day of 2014 when CNY started to fall alongside Treasury note and bond yields. The speculative shorting soon faded into obscurity while global dollar shortage, another one, and the collateral shortage part of it, retook center stage (repo fails spiked a few months further on).

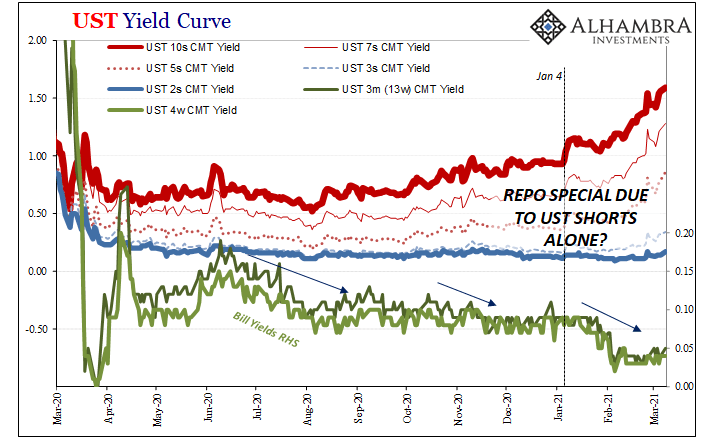

The “good” thing about the eruption of the abrupt outbreak of repo specialness in March 2020’s GFC2 was that there was no mistaking its source. Speculators were hardly rushing to short notes and bonds while their prices skyrocketed on the eruption of outright deflation. Instead, the long-feared collateral bottleneck became a reality and collapsed collateral chains – and market functioning – left and right to the point that only OTR issues were negotiable. And in the aftermath of this GFC2, though there were no new Lehmans, there has been a whole lot of collateral-stripping QE; more than ever! Central bankers love to create bank reserves, in any time period, because that’s all they have. When the sum total of your toolkit is bank reserves, no wonder collateral issues go unappreciated and unfixed even after huge, unmistakable eruptions; not to mention these repeated false reflationary dawns. |

UST Yield Curve, 2020-2021 |

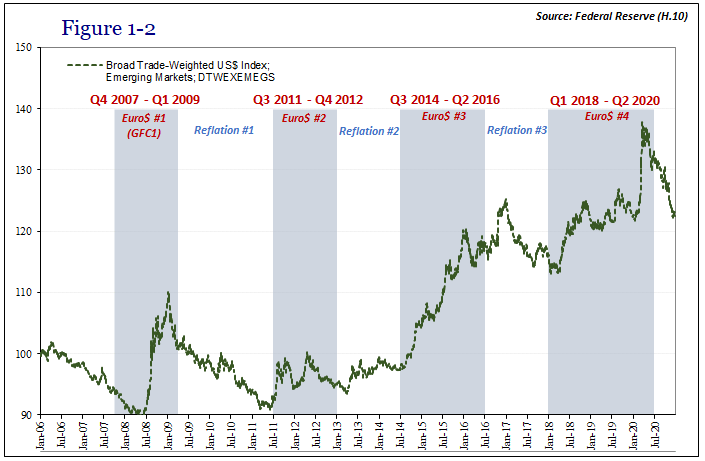

| But in March 2021, it appears as if we are back to the summer 2013 mix of collateral demand sources, therefore the same confusion (because what happened in 2013, what really happened, has never been properly documented and interpreted). There are the shorts who have had reason to be short especially since January operating the same time and in the same space as collateral shortage woes have been re-energized during the very same weeks and months (including a rising dollar denoting rising monetary risks globally). The one end betting, like 2013, reflation in the US system contributing to the specialness already suggested by the usual collateral shortage positioned against it and thus for its perhaps inevitable end.

Will this time be different? Though they amount to the same demand pressures on collateral streams/chains, will the shorts and their reflation basis prove valid in 2021, or, like 2013 (and 2017 or 2010-11), do the wider repo problems (like bills) indicate the same underlying structural deficiencies that had abruptly ended every single one of the reflationary biases up to this point? |

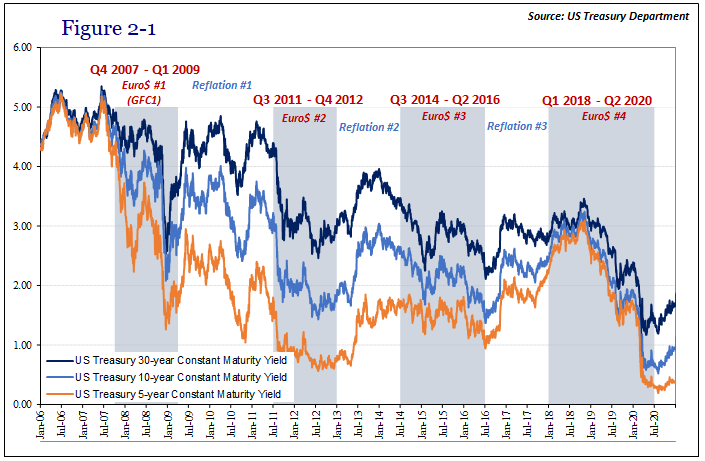

US Treasury, 2006-2020 |

| You can easily tell by the way I worded the preceding paragraph which way I’m leaning. Shorting UST’s and reflation go hand and in hand, just like collateral shortage definitively states that nothing has fundamentally changed underneath all that. Swinging back and forth between temporary reflation and more acute funding problems (global dollar shortage), we won’t get any more than this until, as just the first thing, the collateral shortage gets sorted out.

US central bankers, however, don’t even want to talk about it on the very, suspiciously few occasions asked. That, too, remains unchanged from 2013. |

US Treasury, 2006-2020 |

Full story here Are you the author? Previous post See more for Next post

Tags: Bonds,collateral,collateral bottleneck,collateral shortage,currencies,economy,Featured,Federal Reserve/Monetary Policy,Markets,newsletter,repo