| The ECB appears to be moving closer to activating Outright Monetary Transactions (OMT). Despite being part of Draghi’s “whatever it takes” moment, OMT has never been used. If the Fed’s open-ended QE is seen as dollar-negative, then OMT should be seen as euro-negative. |

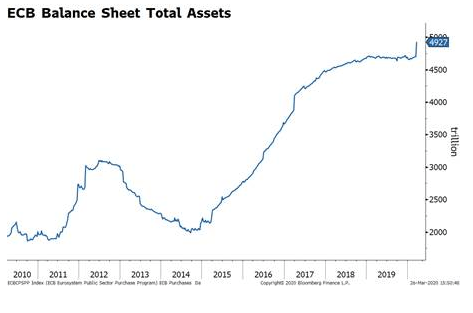

ECB Balance Sheet Total Assets, 2010-2019 |

RECENT DEVELOPMENTS

At the regularly scheduled March 12 meeting, the ECB delivered a package of easing measures that were in hindsight quite underwhelming. The ECB boosted QE by a total of EUR120 bln by year-end, but gave no details on how the purchases will be spread out. Recall that the ECB restarted QE at the September 2019 meeting by buying EUR20 bln per month. The bank offered unlimited liquidity on a temporary basis through additional longer-term refinancing operations (ordinary LTROs) whilst lowering the rate on its TLTROs by 25 bp.

After an emergency call March 18, the ECB announced an emergency bond purchase program totaling EUR750 bln that now includes commercial paper. Lagarde said there were “no limits to our commitment to the euro.” The bank also eased collateral standards. Governing Council member Villeroy later stressed that “Debt markets are our priority, because in the short term they are the most important for financing the economy.”

Today, the ECB removed issuer limits on its emergency bond purchase program. Recall that the self-imposed limit caps the ECB buying to a third of each member state’s total debt. It’s clear that the Fed has opened the door for the ECB to follow it down the past of eventually unfettered bond buying.

POSSIBLE NEXT STEPS

- The ECB could activate Outright Monetary Transactions (OMT). Reports suggest ECB officials are broadly in favor of activating it, but some officials are pushing back. Despite being part of Draghi’s “whatever it takes” moment, OMT has never been used, in part because of the negative stigma associated with it. By allowing unlimited purchases of member country bonds that are distressed, OMT would be, in our view, another large step towards monetization of fiscal deficits.

- The ECB could cut rates. The bank has left the door open to take rates more negative, it’s clearly reluctant to do so due to the potential further harm to the banking sector. Many at the ECB (as well as the BOJ and SNB, it would seem) question the efficacy of negative rates and whether the costs of going more negative outweigh the benefits. Implied rates suggest very low odds of another cut this year. If the bank eventually does cut, however, we expect the ECB will increase so-called “tiering” that allows banks to avoid some of the increased interest charges on their deposits at the ECB.

- The ECB could further increase Quantitative Easing (QE). Recall that the ECB restarted QE at its September meeting to the tune of EUR20 bln per month. While these purchases are open-ended until the ECB meets its inflation target, the amounts are quite small. The recent EUR750 bln emergency QE is a good start to ramping it up further, but the ECB could easily move to a more aggressive stance like the Fed has done. The ECB’s balance sheet stands at around EUR4.7 trln ($5.17 trln) at the end of February.

- The ECB could hold more Targeted Long-Term Refinancing Operations (TLTROs). The last TLTRO (III) was announced in June 2019, began in September 2019, and will end March 2021. This month, the ECB eased the conditions for TLTRO III, cutting the rate charged by 25 bp and boosting eligibility. Peripheral banks, particularly Italian, were big subscribers of previous TLTROs. While more liquidity would help maintain the health of the banking sector, the impact on lending and activity has been limited.

- The ECB could lend directly to corporates. This is controversial, but less so now the Fed has already gone down this path. The rational makes sense: there was some disintermediation going on that was preventing banks from US lending. As such, we cannot rule out the ECB doing something similar.

- The ECB could jawbone the euro weaker. With growing concerns about the economic outlook, a weaker euro really is one of the easiest and surest ways to get some stimulus to the economy. While the ECB professes not to target the exchange rate, that never prevented Trichet or Draghi from making comments that worked to weaken the euro. Of course, without any underlying shift in the interest rate differentials or economic fundamentals, jawboning typically has limited impact.

It’s clear from this menu of choices that room remains for further ECB actions. Yet markets are right to also look to fiscal policy to help offset the coronavirus impact. Even there, fiscal stimulus can only partially offset the recessionary impulses in play. When all is said and done, expansionary policy (whether monetary or fiscal) will do little when quarantines are in effect and supply chains are broken.

| INVESTMENT OUTLOOK

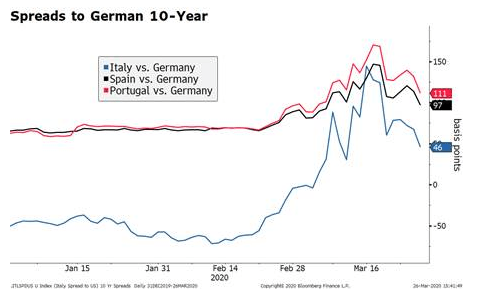

If the Fed’s open-ended QE is seen as dollar-negative, then OMT should be seen as euro-negative. As we noted in our recent Fed piece To Infinity (and Beyond), “The dollar typically does poorly at the onset of each round of QE before recovering. Granted, the sample size is small but it’s all we’ve got.” We also need to emphasize that monetary policy is one variable in a complicated mix of events driving currency pairs, especially in the near term. We maintain our strong medium-term dollar call whilst wholeheartedly admitting that the Fed has made it harder to maintain over the short-term. Since the Fed’s move to open-ended QE, we are seeing knee-jerk selling of the dollar but we believe it will eventually recover. Why? Virtually every major central bank is engaging in near unlimited QE with zero rates, with the ECB likely to continue expanding its program. As such, every currency is now more or less on a level playing field. Despite the dire near-term US economic outlook, we maintain our view that the US economy remains best-positioned to deal with the effects of the coronavirus and that the dollar should ultimately benefit from this. Contrast this with Germany and Italy, who were already teetering on the edge of recession in Q4. Peripheral eurozone spreads should continue to fall. Madame Lagarde quickly realized her error in saying that “We are not here to close spreads.” That was and will remain an integral role for the ECB as Italy and other peripheral countries ramp up spending and debt issuance in the coming months. The ECB will not be happy with a stronger euro. It traded today at its highest level since March 17. Major retracement objectives from the March sell-off come in near $1.0965 (38%), $1.1065 (50%), and $1.1165 (62%). The 200-day moving average comes in near $1.1080 currently. Draghi often pushed back at euro strength during his tenure, let’s see how Lagarde approaches it going forward. If the euro continues to gain, we believe Lagarde is likely to push back against it. |

Spreads to German 10-Year |

A BRIEF HISTORY LESSON

Mario Draghi succeed Jean-Claude Trichet as ECB President in November 2011. He was endorsed by German newspaper Bild as “the most German of all remaining candidates.” Little did Bild know just how un-German Mr. Draghi would turn out to be, as he promptly reversed Trichet’s two final hikes with cuts at his first two meetings on November and December 2011.

With the eurozone crisis in full bloom, Draghi was forced to become even more aggressive. He will best be remembered for his July 2012 pledge to “do whatever it takes to preserve the euro” and it wasn’t just rate cuts. From that pledge, the ECB announced its Outright Monetary Transactions (OMT) program in August and details finalize in September 2012.

OMT allows the ECB to buy the sovereign bonds of any distressed country. In order to qualify for OMT, a country first has to ask for assistance from the eurozone’s European Stability Mechanism and European Financial Stability bailout funds that were established during the eurozone crisis, which come with strict conditionality. Once OMT is approved, there are no limits to how much of a country’s debt that the ECB can buy. To this day, it has never been used.

The ECB came late to the QE game. It wasn’t until January 2015 that the ECB announced it would start Quantitative Easing (QE). QE began at the March 2015 meeting at a pace of EUR60 bln per month and peaked at EUR80 bln per month in 2016. Tapering began in April 2017 with purchases falling to EUR60 bln per month and continued in January 2018 when it cut its monthly purchases in half to EUR30 bln. In June 2018, the ECB announced it would lower its monthly purchases to EUR15 bln in Q4 2018 before ending altogether in December 2018. And that’s where we stood until the ECB restarted QE in September 2019.

Full story here Are you the author? Previous post See more for Next postTags: Articles,developed markets,newsletter