Another local election in Germany, another stunning defeat for the ruling center. How many more of these does anyone need before they realize the electorate is going to keep migrating toward the poles? And it all stems from the one reason; there is no and has been no economic growth. But because the so-called establishment has insisted the economy is booming, or it was, people are doing what people always do.

They look for someone, anyone who can give them a plausible explanation for a world that doesn’t fit the conventional narrative.

The hustings in the German state of Thüringen have concluded with a plummet in support for Angela Merkel’s CDU party.

The winner, or leading the vote share, was the far-left Die Linke gathering about the same proportion as in the prior election. But while the CDU lost double digits, the far right AfD party gained pretty much all of those votes to finish second ahead of them.

For some reason, the mainstream media continues to be stunned at these results.

The populists and extremists across Europe are Mario Draghi’s legacy. It all stems from his one big, crucial error. In July 2012, he promised to “do whatever it takes” to save the euro and preserve the European Union. The ECB’s President, however, thought that Europe’s big threat was nothing more than the fiscal risks of Club Med.

His big plan was thus designed to combat high interest rates on PIIGS debt. He did next to nothing about any monetary shortfalls that were obvious at the very beginning of his tenure. His predecessor, Jean-Claude Trichet, had left an unquestionable huge mess for Draghi – because Trichet didn’t get it, either.

I wrote more than two years ago on the fifth anniversary of Draghi’s promise:

Being in charge of Europe’s central bank at that moment in time was no easy job. The Continent was beset by enormous problems seemingly on all sides. Not even a year before, the European banking system nearly fell into its own Lehman moment (what was it that actually happened on December 8, 2011?), leaving the ECB to scramble up nearly €1 trillion in “liquidity” (LTRO’s).

And still it didn’t seem to be working. The banking crisis faded, as they always do, but the effects of it did not. By summer 2012, the euro seemed to be coming apart. The immediate problem was the euro’s apparently fatal tie between very different economic systems; this North/South divide, or PIIGS versus largely Germany. Peripheral European bond spreads had blown out, suggesting that there were deeper problems than simply short run liquidity.

On the narrow score of those bond spreads, Mario was a success. Hooray for him and him alone. They came back down to earth and from that point forward there has been little mention of anyone’s southerly fiscal situation.

|

Central Bank Failure, 1999-2019 |

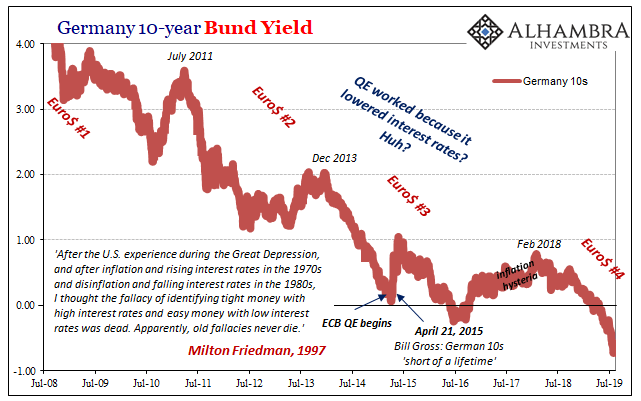

| That’s what the big fuss in 2017 and early 2018 was all about. Surely after so much “highly accommodative” monetary policy once policymakers in Europe (around 2014) realized that PIIGS really hadn’t been the problem, finally hitting the QE button the positive effects would all come tumbling out in the form of an inflationary breakout. They kept telling everyone, Mario especially, that it was coming. It was all but certain to come.

Quite predictably, it never came. Thus, Draghi leaves the ECB in the same shape, worse shape than in which he found it. A total mess. His promise to maintain the euro is at more risk today than at any other time – including back in that hot summer of 2012 when Portuguese and Greek bond yields surged into the stratosphere. After so much time and so much wasted effort, there is only one conclusion to draw – they must be missing something. Forget about what that might be for a moment, the way things have turned out and keep turning out that’s really the most important takeaway. In election after election, in economic data as well as market prices, everything keeps pointing in that same direction. And it’s the one possibility they never even consider. |

Germany 10-year Bund Yield, 2008-2019 |

At an impasse, the situation spirals more and more out of control.

What’s changed, and this is the really important bit, is that the consequences of getting it all wrong are no longer purely financial or fiscal. That’s not to say that there aren’t deep, unabating financial risks because there obviously are. Those have been superseded by political and social risks as the angry voting public is tired of hearing about a boom that never booms. The people may superficially agree with Draghi and call it that, but underneath they know and feel the difference and thus act out in anger.

People in Europe as everywhere else have been incredibly patient. Think about this: Mario Draghi is retiring after two four-year terms at his job. That’s eight years, an incredible amount of time having been squandered by utterly ridiculous policy schemes. Once you see them for what they really are, the whole Continent’s predicament makes perfect sense.

The moneyless monetary policies are the problem; that’s why there was never any inflationary acceleration. Trillions in actual money printing would have undoubtedly showed up in that form. Since it didn’t, and Europe has certainly given it enough time already if it ever was going to show up, we know for certain it was never money printing (no matter what they say and rationalize in the stock market).

The economy and now the electorate keep on demonstrating all the sustained effects of smoke and mirrors, trying to manipulate public expectations at the expense of monetary substance. If anything, it has been this absurd idea that a central bank can combine the puppet show of QE with forceful proclamations of a boom and therefore create one out of nothing. Even Keynes would be horrified.

But having said a boom was coming and then claiming 2017 and 2018 was one, can you really blame Germans and other Europeans for going somewhere else? If that was a boom, the best Mario Draghi could do, there is no need to try and explain populism right or left. Tearing it all down and starting fresh seems downright rational.

Especially in light of how Europe’s got at least four years of Christine Lagarde. The even bigger threat to the euro and the European Union. Even more of a risk than Draghi leaving the economy as he found it – on the verge of a recession.

It isn’t that there was one when he started and that there will be one, if there isn’t already, when he finishes. It’s that there was never a recovery in between no matter what he said, did, or tried. Mario Draghi didn’t break his promise so much as he didn’t have any idea what he was promising.

It’s not the recessions or recession risks that are the world’s big problem. It’s the absence of any recovery anywhere on it. Europe is a prime example, but sadly not alone in this state. I’d write good riddance Mario, but the next one is already well-entrenched. They never change, so something else will have to. And it surely is.

Full story here Are you the author? Previous post See more for Next post

Tags: currencies,economy,Federal Reserve/Monetary Policy,Markets,newsletter