Small businesses on the precipice need only one small shove to go over the edge, and there won’t be replacements filling the fast-multiplying empty storefronts.

As a generality, the average employee (including financial pundits) has no real experience or understanding of what it takes to start and operate a small business in the U.S. Government employees in the agencies that oversee and enforce regulations on small businesses also generally lack any experience in the businesses they regulate.

A third generality is the endlessly promoted ethos of entrepreneurism cultivates the illusion that there is an essentially endless supply of entrepreneurs who are itching to start businesses and throw everything they have into the risky gamble.

All we ever hear when a restaurant owner is interviewed is how much they love their business, their work, their customers, their neighborhood, etc. etc. Sadly, enthusiasm isn’t enough to pay the rent when belt-tightening reduces sales while costs notch ever higher.

The story plays out the same everywhere; the only variation is the relative scale of the costs that are squeezing small businesses and the limits on how much they can raise prices:

America’s Highest Minimum Wage Sparks Fight in Small California City: Restaurants in Emeryville say they can’t keep raising prices, but workers say $16.30 an hour is barely enough in the Bay Area.

For those of you who don’t read the entire article: one cafe owner reports that she netted a whopping $5,000 in a good year, her entrepreneurial payoff for working insane hours and putting up with the ceaseless grind of keeping her business afloat.

The reality is very few people have the drive, risk appetite, capital and experience to start and operate a small business. Once this pool of people has been exhausted or bankrupted, the number of new small businesses plummets and does not recover.

Another reality is a great many bricks-and-mortar Main Street businesses are on the precipice of closing. There are two primary drivers of this systemic vulnerability:

1. Costs are rising far faster than enterprises’ ability to raise prices for the goods and services they sell

2. Wages and salaries (earned income) has stagnated for the past 20 years for the lower 95% of households while costs of big-ticket expenses such as rent, healthcare, college, childcare and government services and taxes have risen sharply.

This leaves less discretionary income available to spend on non-essentials, i.e. “experience consumption.”

Simply put, small business expenses are rising while their customers’ stagnating income means there is little leeway to raise prices. Small business is in a vise.

There’s another dynamic in bricks-and-mortar businesses that must rent commercial space. The bubble in real estate valuations has spread to commercial real estate in many if not most urban areas, but certainly to every urban area with a vibrant job market–exactly the sort of place that attracts those willing to start a new business.

If a retail building was worth $1 million a decade ago, and now it sold for $3 million, the new owners naturally expect rents to cover all expenses and yield a 5% return on their investment.

The new owners don’t think of themselves as greedy; a 5% return on capital is conservative.

The higher price doesn’t just increase the size of the mortgage and the monthly payments; it also increases the property taxes due. Since the fees charged for government services are soaring, business licenses, permits, etc. have also increased far faster than official inflation.

For the investment to pencil out for the new owner who paid $3 million for the building, the rent for each space has to triple from $1,000 a month to $3,000 a month.

How many small businesses can afford a doubling or tripling of rent? Since wages, healthcare, licenses, permits, etc. have increased dramatically while the ability to raise prices has been constrained, many small businesses can’t afford even a 20% increase in rent, never mind 200%.

(Note on interest rates: even if the interest rate on the commercial-property mortgage declined a bit, that doesn’t offset the much larger principal payment required since the mortgage tripled in size, nor does it reduce the property taxes or other fixed costs. In other words, the interest part of the owners’ monthly expenses is not the key metric.)

Now let’s factor in a recession or slowdown, a period of consumer belt-tightening that causes revenues to drop.

A great many Main Street businesses paying market rents are only making money in the very best of times. Any slowdown, however modest, pushes them into the red.

If they expect revenues to pick up in a month or two, small business owners will absorb losses, cut the hours of employees, work longer hours, etc. But if the revenues don’t recover while expenses click higher, the entrepreneur eventually has no choice: either close down now or go broke via the drip of monthly losses.

Once the slowdown is undeniable, no one with any moxie is going to step up and pay market rent on the vacant space. The inexperienced souls who try their hand in the new space will be bankrupted in a matter of months by the high rent.

The building owners are loathe to drop the rent from $3,000 a month to $2,800, much less to $2,000 a month. Yet the reality is that no small business can afford more than $1,000 a month.

The building owners are caught in their own vise: they need rents close to $3,000/month to cover their expenses, and so dropping rents to what small businesses can afford will result in horrendous monthly losses. But leaving the spaces vacant generates losses, too.

The only way out is to default on the mortgage and abandon the building to the lender, who then faces enormous losses because the building is no longer worth $3 million since rents have crashed.

Neither the commercial building owners nor the small business tenants have any wiggle room. The only alternative to increasing losses each has is to close down the business / sell the building for a huge loss or default on the mortgage.

All the increasing costs are famously sticky: wages don’t go down, healthcare costs don’t go down, city fees don’t go down, and rent goes down only grudgingly, in increments too small to save small businesses operating in the red.

And since the pool of experienced entrepreneurs is small (and shrinking as people burn out, go bankrupt, retire, etc.), the empty storefronts will stay empty for a long, long time– until rents drop back to levels that enable small businesses to make a profit in recessionary times.

Nobody wants to see building valuations decline by 2/3 or more: cities, lenders and investors all want valuations to notch higher or at least remain stable. But bubble-era valuations lead to rents that are completely unaffordable, so small businesses will close, resulting in the rental income dropping to $0 per month.

Since all the costs are sticky and expectations are wildly unrealistic, there is no painless way forward.

|

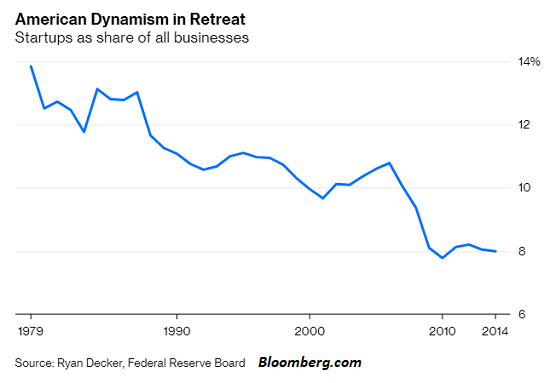

Small businesses on the precipice need only one small shove to go over the edge, and there won’t be replacements filling the fast-multiplying empty storefronts. The hurdles, costs and risks of starting a new enterprise notch ever higher while the rewards diminish. No wonder startups are in systemic decline: we’ve made it so difficult to start and operate a small business that few have the skills, stamina and capital to survive, much less thrive.

Blowing a real estate bubble that crushed small business may well be viewed in hindsight as the Federal Reserve’s cruelest and most destructive policy error.

|

Startups as Share of all Businesses, 1979 - 2014 |

Tags: newsletter