Just ahead of Sunday’s general election, there is little sign of appetite among the leading parties to tackle the significant challenges that Italy faces.

|

The Italian general election campaign is in its final stretch before voting on 4 March. The election will take place under the new electoral law (Rosatellum bis), which allocates 37% of parliamentary seats via the principle of “first-past-the-post” and 61% via proportional representation, with the remaining 2% reserved for overseas constituencies (see our previous Flash Note for further details).

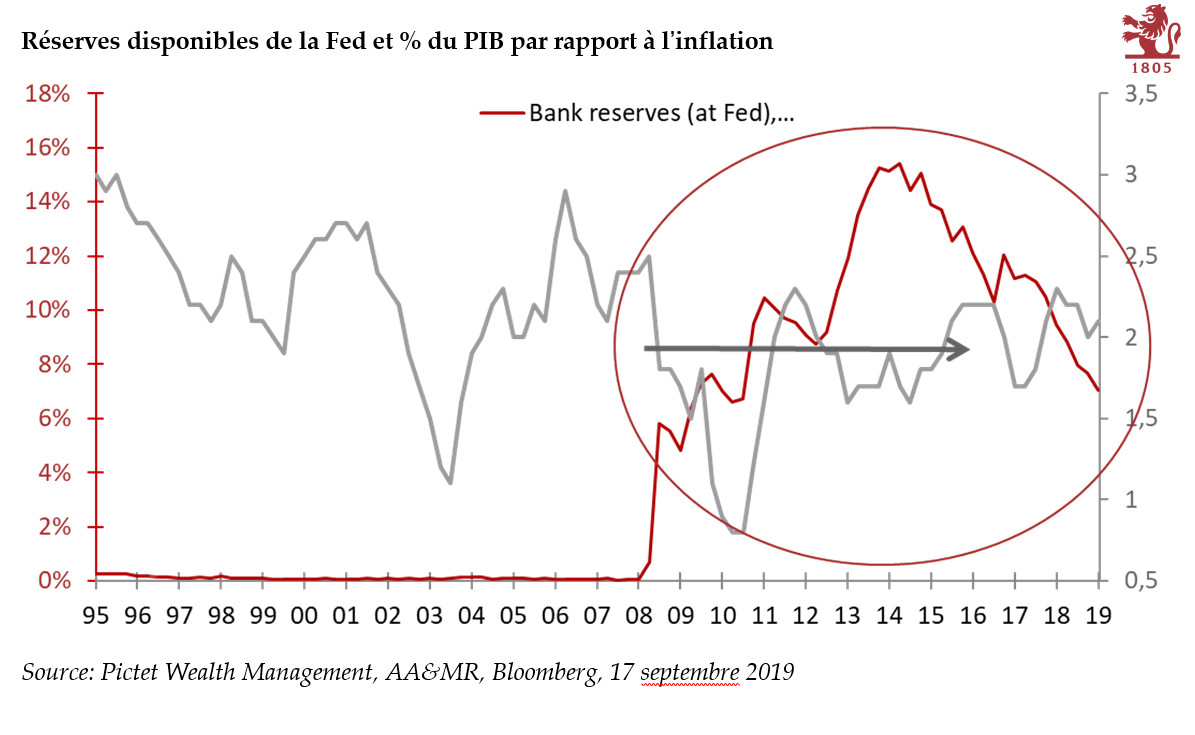

According to the last polls published before the blackout period (Italian law prohibits poll publication during the two weeks preceding elections) no single party or coalition was projected to win an outright majority (see Chart below). But the centre-right coalition formed by Forza Italia (FI), Northern League (LN) and Brothers of Italy (FdI) was seen as close to obtaining an outright majority. Within the coalition, the more moderate FI was seen as beating its right -wing and Eurosceptic ally LN, but the gap remained small, according to the polls. Meanwhile, Five Star Movement (5SM) remained the single largest party, according to the pollsters, but it was still far from achieving an outright majority, while the decline in support for the Democratic Party (PD) seemed to have stopped.

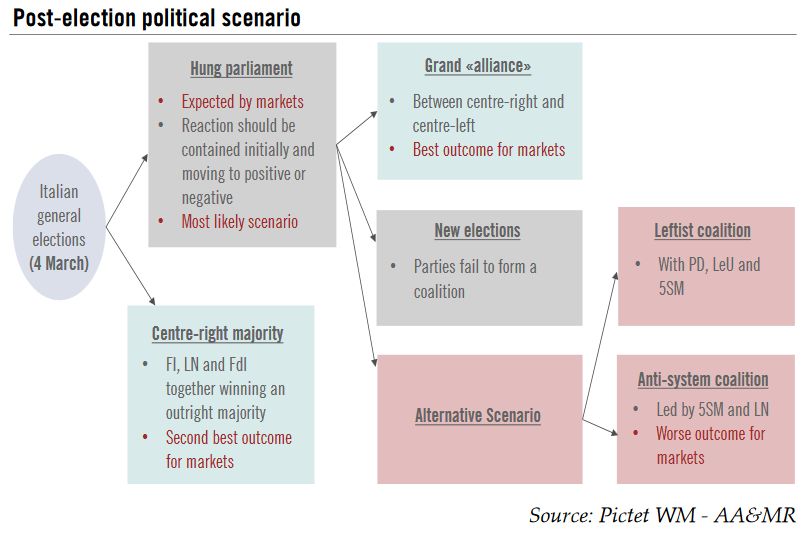

That being said, the new electoral system and the fact that 37% of seats are to be allocated on a ‘first-past-the-post’ system make projections particularly hard. Moreover, the number of undecided voters remains high (still around 1/3 of potential voters, according to the latest polls). But if the opinion polls are correct, no political party or coalition will obtain a majority in the 4 March election. Thus, a hung parliament, at least initially, is highly possible (see Diagram below). If this happens, President Sergio Mattarella will call on parties to negotiate to form a government. Months of talks will probably follow before some sort of agreement is found. A grand alliance between Forza Italia and the PD (with support from smaller centrist parties) could emerge from this process.

Another possibility could be an outright majority for the centre-right coalition. The last opinion polls suggested that the centre right was just 20-30 seats short of an outright majority. While the position of the coalition is well established in northern and central Italy according to a recent analysis, the situation in the South is still open and could conceivably help the centre-right coalition achieve a parliamentary majority. Should this happen, the key question will be who will lead the coalition. There is an informal agreement that the party wining most support gets to pick the prime minister. Former Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi is ineligible because of his conviction for tax fraud. He has indicated that he would like Antonio Tajani, the current president of the European Parliament, to take the role. The choice of prime minister will be followed closely by markets, with a coalition led by the moderate and pro-Europe Antonio Tajani likely to be preferred to a government led by Matteo Salvini, leader of the Northern League. Although the centre-right parties have agreed a common political platform, Berlusconi and Salvini’s pronouncements have diverged on several topics.

|

Average Monthly Voting Intentions, Jan 2016 - Jan 2018 |

Election manifestos: let’s spend some moneyItaly is going into elections in good cyclical shape, but while near-term risks seem to be contained, medium-term challenges are likely to be a key focus for investors. Compared with its euro area partners, Italy’s potential growth is low, and youth unemployment (persons aged between 15-24 years old) is at about 35%, among the highest in Europe. The country has the second-highest debt load in the euro area after Greece (132% of GDP). Over the past few years, Italy has endeavoured to address certain structural issues, but more steps need to be taken to lift the Italian growth rate to a sustainably higher level.

Whatever Italy’s next government looks like, the chances that it will push through long-term structural reforms to improve economic performance or to tackle the country’s public debt appear low. Based on election promises, the situation could even worsen. All parties are pledging significant expansionary policies (see Table below). Cutting tax is an important part of the programmes of the centre-right parties, with LN and FI proposing a flat tax. Repealing the 2011 Fornero pension reform features prominently in both the centre-right and 5SM manifestos. Such policies would likely put Italy on course for a confrontation with the European Commission over fiscal consolidation and deficit reduction targets at some point. Already, Italy is not in compliance with EU fiscal rules. Unless there are compromises (which is the most likely), the Commission could be forced to open a procedure against Italy in the coming months (Italy is to present an update on its fiscal situation in April-May). Rising tension with the EU and fiscal slip page could further heighten market concerns about Italy’s debt sustainability.

Significantly, Italian parties have dropped proposals to hold a referendum on the euro.

|

Post-Election Political Scenario |

Tags: Macroview,newslettersent