|

The Federal Reserve is probably looking back at 2017 with satisfaction. After on the rate rise expected on 13 December, it will have pushed through the three rate hikes it signalled earlier in the year. For once, it has not under-delivered. Meanwhile, the gradual, ‘passive’ decline in the Fed’s balance sheet has been mostly ignored by markets. In fact, broader financial conditions have eased this year despite the Fed’s monetary tightening. Corporate bond spreads, for instance, have remained very tight and bond issuance has flourished. It is precisely because broader financial conditions are seen as too accommodative by many Fed officials that the Fed is ready to ignore the persistent under-shoot in core inflation and to continue hiking rates, in our view.

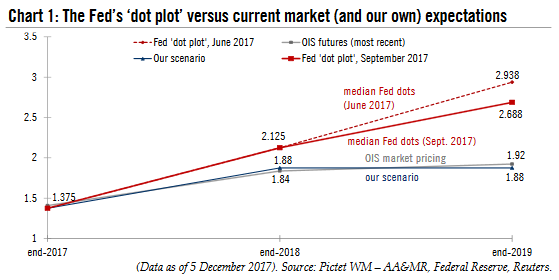

We think the Fed is focused on reaching a nominal rate of about 2% in the coming quarters. After the probable December rate hike, we expect two further rate hikes in 2018 (in March and June) . The risks to our view are tilted slightly to the upside due to the potential confidence-boosting effect of tax cuts. Even though the prospect of tax cuts means the Fed could adopt a more hawkish style of communication, we do not believe they are a game changer when it comes to the Fed’s plans for normalisation. Key is core inflation. Given our forecast for core PCE inflation to remain below 2%, we expect the interest rate on excess reserves (IOER) to plateau at 2.0% in June 2018.

We do not think the ‘changing of the guard’ at the Fed board, including the appointment of Jerome Powell as Fed Chair, will impact the Fed’s reaction function in the coming quarters. Powell, a long -time Fed insider, has insisted on continuity with his predecessors, Janet Yellen and Ben Bernanke. There remains some residual uncertainty about the other vacant seats, however.

|

The Fed's "dot plot", 2017 - 2019 |

Change of guard at Fed board: we expect continuityThere has recently been significant turnover of Fed board members, even though our view is that the actual change in policy direction will be quite modest.

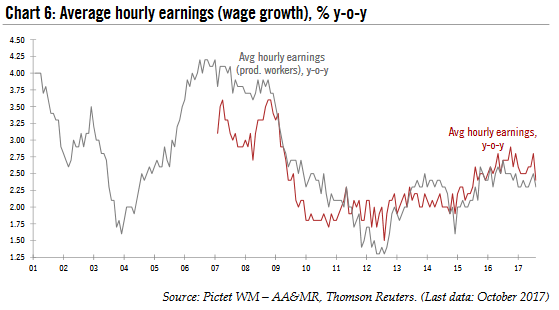

President Trump has decided not to reappoint Janet Yellen for a second four-year term, preferring Jerome Powell (a Fed governor since 2012). Yellen has said she will leave the Fed once Powell is sworn in, probably early next year. We see Powell as being in the same mould as Yellen when it comes to monetary policy. Like Yellen, Powell is sensitive to slow wage growth and low inflation. He is also aware of the low real neutral rate estimates produced by the Fed staff. He remains alert to markets’ interpretation of his pronouncements and will probably continue to avoid abrupt changes in rhetoric. In short, Fed policy moves should remain well telegraphed.

There is no formal replacement yet for Stanley Fischer, who left his role as Vice Chair of the Fed in October. The media has mentioned that Mohamed El-Erian, a former ‘star’ asset manager and well-known financial commentator, is being considered for the role, along with other candidates. If appointed, El-Erian would bring strong market expertise to the Fed board.

Trump has also nominated Marvin Goodfriend to the Fed board.Goodfriend, a Carnegie Mellon university professor and former Richmond Fed economist, has the reputation of being a ‘hawk’, since he has criticised the Fed for engaging in quantitative easing (QE) policies in recent years and for deviating on interest rates from standard models like the Taylor rule.

Some commentators have recently tried to portray Goodfriend as a potentially

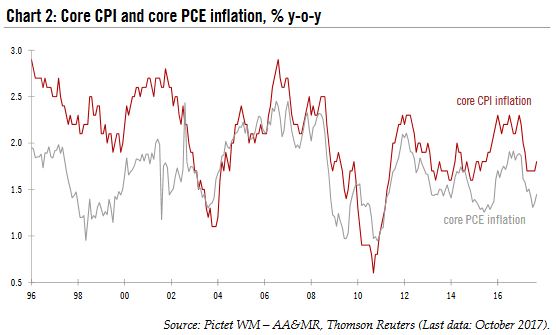

dovish influence, in the sense that he would care about the persistent missing of the inflation target and the risk that inflation expectations remain anchored at low levels. Core PCE inflation has averaged only 1.56% over the last five years, significantly below the 2% target.

|

Core CPI and Core PCE Inflation, 1996 - 2017 |

|

By contrast, we think Goodfriend is more anxious about future rather than past inflation, and he is perhaps less attached to core PCE than the other inflation measures (core CPI has averaged 1.9% over the last five years, for instance).

Overall, we would characterise Goodfriend as slightly hawkish. More importantly, we think that his influence will remain moderate and that he will adapt to the consensus-oriented nature of the Fed. His action as policy maker could be mellower than his words as an outsider, in our view. In spite of his slightly hawkish views, we doubt that he will cause the Fed to veer significantly from its current direction.

Trump is focused on the Fed’s role as banking regulator , probably more so than on its monetary functions. Deregulation has been a key priority for the Trump administration. The many rules put in place since the financial crisis and their interpretation by agencies like the Fed have put an unnecessary burden on the banking community, in the administration’s view. It is in that context that Trump placed Randy Quarles, seen as strongly in favour of banking deregulation , as Vice Chair responsible for banking supervision. The banking supervision role had previously been informally occupied by Daniel Tarullo, who stepped down from the Fed in April 2017.

Jerome Powell has mentioned to Senators that he sides with the Trump administration’s goals of lighting up on regulation, although he is more for “tailoring” regulation than wholesale deregulation. It will be interesting to see how the relationship between Powell and Quarles evolves, and whether Quarles pushes for more far -reaching deregulation than Powell. The two men know each other well, as they worked at the same Washington DC-based private equity fund in the early 2000s.

With further staff changes in the months ahead, there remains some uncertainty about where the Federal Open Market Committee’s (FOMC) centre of gravity will be in the coming quarters. First, it is not clear whether governor Lael Brainard, a former key ally of Janet Yellen and key policy dove in recent years, will stay at the Fed. We assume she will, especially as she has tended to focus on ‘fintech’ questions lately and refrained from commenting much on monetary policy itself.

|

Real Neutral Rate, 1996 - 2017 |

|

Her last speech was “Where do consumers fit in the fintech stack?” at the University of Michigan in mid -November. In other words, Brainard may stay at the Fed, but be more nuanced about her dovish views on monetary policy than in recent years.

One vacant seat at the Fed board is set to go either to a community or regional banker, or even a local bank regulator. During the summer, the names of Richard Davis and John Allison (both former CEOs of regional banks) were circulating, although more recently website Politico reported the seat may go to Michelle Bowman, a Kansas State Bank Commissioner.

At the risk of generalisation, we would say that while representatives of local communities tend to complain about low interest rates (and local bankers about how flat yield curves affect interest margins), in practice they tend to be major supporters of slow normalisation and of keeping financial conditions loose. The US agricultural sector has had a wild ride lately due to the fall in crop prices. Irrigated land values were down 5.9% y-o-y in Q3 2017, for instance. We would therefore expect people with a more rural background to refrain from adding to calls for significantly tighter financial conditions.

Another question mark is who will be the next New York Fed president after Bill Dudley quits next summer. Dudley has been another important dovish ally of Yellen’s. But Dudley has become more anxious about excessively loose financial conditions on markets lately and more comfortable with continuing the rate-hiking cycle despite low inflation. The New York Fed, which has a permanent voting seat at the FOMC, tends to have a crucial influence on monetary-policy decisions and this future appointment needs to be watched closely. While selection is made at the local level, the decision needs the consent of the Washington DC-based board of governors.

Each year, four of the FOMC’s regional Fed members rotate. We tend to downplay the importance of this annual rotation on the direction of policy since we have seen over the years that effective power lies with the Fed board and the New York Fed.

|

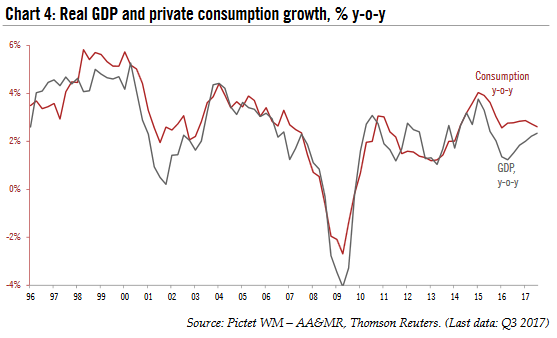

Real GDP and Private Consumption Growth, 1996 - 2017 |

|

We do not see any hawkish risk resulting from this year’s rotation , which will see the appointment of the presidents of the Fed Banks of Cleveland (Mester, a hawk), Atlanta (Bostic, rather dovish), San Francisco (Williams, centrist) and the new Richmond Fed president, Tom Barkin. The latter is a former partner of a major consultancy firm. We do not know his exact policy views but we assume he will remain pragmatic on monetary policy (by background, his focus seems to be more financial regulation and interest in banking affairs).

Fed regime: unlikely to change under PowellDebate is growing inside the Fed about a new monetary policy regime. The San Francisco Fed president John Williams has recently advocated a price-level targeting regime rather than the current inflation-targeting one. While still in its infancy, we think the debate reflects some underlying anxiety that the Fed may be ill equipped to respond adequately to the next economic downturn given that interest rates are already low and the Fed’s balance sheet is bloated. However, we think a regime change at the Fed is highly unlikely in 2018-19.

Instead, Powell, a lawyer by education and a former private equity executive,

is likely to continue the policy of de facto flexible inflation targeting followed by Yellen and Bernanke.

There are two important aspects to the Fed’s policy approach, in our view. First, core PCE inflation remains the key variable to watch, possibly dictating whether the Fed’s hiking cycle continues beyond 2%. The Fed remains highly attentive to the Phillips curve framework, which links a tight labour market to stronger inflation. This explains why the Fed has been disposed to dismissing recent low core inflation prints as temporary (buoyant financial markets are a further incentive to sideline low core inflation for now).

Another important parameter is the Fed staff’s view about the ‘theoretical neutral rate’, which is the underlying (or theoretical) rate that takes into account savings and investment (with a strong input from productivity growth) and therefore a key rate against which Fed rates are benchmarked.

|

US Treasury Yield Curve, 1985 - 2017 |

|

The Laubach-Williams estimate – the ‘reference’ for Fed staff – continues to indicate that real rates are close to zero. This low neutral rate is a major reason for the slow pace of Fed tightening and suggests the Fed’s hiking cycle is likely to remain shallow.

Regarding the balance sheet, the Fed has already signalled that the bar for revising the parameters of its plans for passive reduction of its bond holdings – released at the September meeting – is very high. Powell has indicated that the Fed should continue shrinking its balance sheet for another three or four years. That said, Powell has also said that strong demand for banknotes in recent years will lead to a Fed balance sheet that is higher than before the financial crisis (banknotes are a liability for the central bank). We think it is highly unlikely that the Fed will revisit its balance-sheet plans unless there is a significant slowdown in the economy.

December meeting: rate increase probably ‘baked in’In the near term, the FOMC looks highly likely to hike rates by 25bps when it next meets on 13 December. The most recent, and clearest, signal came from Powell’s testimony before Congress on 28 November. He said the case for a rate hike is “coming together”. As of 5 December, the fed funds market was pricing a 98% probability of a December rate hike, according to Bloomberg data, so it would be a major surprise if the Fed were not to deliver.

During his testimony, Powell – who will probably become Chair in February – insisted that the recent solid economic backdrop warrants a further rate increase. Other Fed board members, particularly some regional Fed presidents, have also voiced their fears of mounting financial imbalances (and risk of a financial bubble) to justify the coming rate increase. Low core inflation, while still being mentioned, has been widely dismissed as “temporary” by various Fed officials, from board members to regional Fed presidents.

The focus at the December meeting may be on the ‘dot plot’, the Fed’s projected rate-hiking path. We do not expect significant changes. In particular, we do not think the Fed is ready to flatten its expected rate -hike path once more. Recent growth data has been solid and business surveys (to which the Fed is very sensitive) have been buoyant.

|

Average Hourly Earnings, 2001 - 2017 |

In that context, we think the 2018 median rate could stay at 2.125% , still indicating three rate hikes next year. This would continue to be above current market expectations of an end -2018 rate of 1.84%. Some Fed officials could react to the recent Senate tax bill and raise their dots, but we think the tax bill was already discussed (and incorporated) at previous meetings. In addition, some Fed officials, still unsure about the scope of tax cuts, could wait until a final tax bill is passed before raising their dots.

The focus will also be on the ‘longer run’ interest rate, a proxy for the nominal neutral rate. We think it will also stay unchanged, at 2.75%. Productivity data has been improving lately , moving to 1.5% y-o-y in Q3 – 2017 from 1.3% in Q2. That said, the improvement is not large enough to warrant an increase in that terminal rate, itself dependent on the Fed’s view for the theoretical neutral rate. As of Q2 2017, the widely used Laubach – Williams model put the underlying real neutral rate at – 0.22%.

Risk to our view: the effect of tax cuts on confidence

At the moment, the risk to our Fed rate hike trajectory (two rate hikes next year on top of the likely December 2017 increase) lies slightly to the upside ,mostly related to tax cuts.

While it is mooted that the corporate tax cuts may not come into force before 2019, the more immediate confidence effect will be key to watch , potentially leading to a slightly stronger growth trajectory than we currently assume. We note that there is an ongoing dichotomy between buoyant surveys and more moderate ‘hard data’: we will need to watch whether hard data move up more significantly in future months. This narrowing could also depend on the details of the tax cuts (Congress’ conference committee should be monitored closely) and how financial markets react.

Stronger -than-expected growth in H1 2018 could mean the Fed becomes less concerned about enduringly low core inflation than we currently expect. In all cases, we think that low core inflation will prove a key barrier to further tightening in H2 2018. While the US labour market is tight, global factors and ongoing technological change as well as the ongoing moderation in medical prices mean inflationary pressures are still contained. These factors should continue to play a role next year , in our view.

Tags: Macroview,newslettersent