A number of people have forwarded this Bloomberg article – Wall Street Banks Warn Downturn Is Coming – to me over the last couple of days. That fact alone is probably a good argument to ignore it but I can’t help but read articles like this if for no other reason than to know what the crowd is thinking.

The gist of the article is that a bunch of sell side analysts think we are nearing the end of the current business cycle and that has them worried about stocks and credit. If that is true – that we are nearing the end of the cycle – then it is certainly reason for concern. The biggest stock market losses are generally associated with the onset of recession, although not always. For instance, in the last recession the onset of recession was December of 2007 and the stock market peaked in November. The previous recession started, officially, in March of 2001 but anyone who waited that long to reduce their stock exposure took a pretty big hit on his stock portfolio. The S&P 500 peaked in March of 2000, a full year before the recession, and was down 25% by March of 2001. So, maybe we need to look at what these sell side analysts are saying and see if it makes any sense.

The first thing to realize is that the dating of recessions is somewhat arbitrary. When we see those gray areas on the FRED charts indicating recession, those dates are ones chosen by the NBER Business Cycle Dating Committee. Here’s how they define recession:

The NBER does not define a recession in terms of two consecutive quarters of decline in real GDP. Rather, a recession is a significant decline in economic activity spread across the economy, lasting more than a few months, normally visible in real GDP, real income, employment, industrial production, and wholesale-retail sales.

A pretty subjective definition if you ask me. Furthermore, the dating of the recession by the NBER is done with the full benefit of hindsight. The last recession, which started in late 2007, wasn’t announced by the NBER until December of 2008 after the worst of the crisis was over. The 2001 recession wasn’t announced until November 2001. So, if you are going to use the onset of recession as a stock market indicator, you better have something to base it on other than the judgment of the NBER. The point being that what the sell side guys are trying to do is worthy. Whether the things they cite as warnings are of any use is a different story.

When you look at the quotes in the article from these banks – who all missed the onset of the last recession/bear market by the way – they don’t really say much beyond “we think this might possibly be something to worry about”. Take the Morgan Stanley quote:

“Equities have become less correlated with FX, FX has become less correlated with rates, and everything has become less sensitive to oil,” Andrew Sheets, Morgan Stanley’s chief cross-asset strategist, wrote in a note published Tuesday.

His bank’s model shows assets across the world are the least correlated in almost a decade, even after U.S. stocks joined high-yield credit in a selloff triggered this month by President Donald Trump’s political standoff with North Korea and racial violence in Virginia.

Okay, so assets are less correlated than they have been in the recent past. Is that a risk? Actually, if you run a diversified portfolio with multiple asset classes, less correlation is probably a positive. Also, the article mentions that “US stocks joined high-yield credit in a selloff” but provides no context for that. The fact is that the change in credit spreads – which is really what matters for high yield and stocks – has so far been too small to be meaningful. Our research shows that anything less than a 10% move in a month is usually nothing more than noise. Even if you wait for a monthly 10% change in spreads, you will be responding to a lot of false signals. You need other indicators to confirm the stress indicated in spreads. As for the “political standoff with North Korea and racial violence in Virginia”, if that is why the market sold off – and by the way we’re off all of 2% from the peak; is that what qualifies as selloff these days? – I wouldn’t spend a lot of time worrying about it.

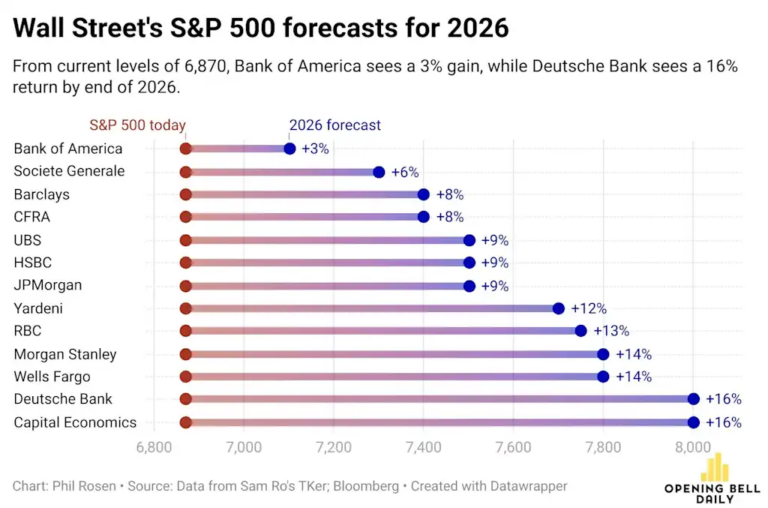

What about this one from Bank America:

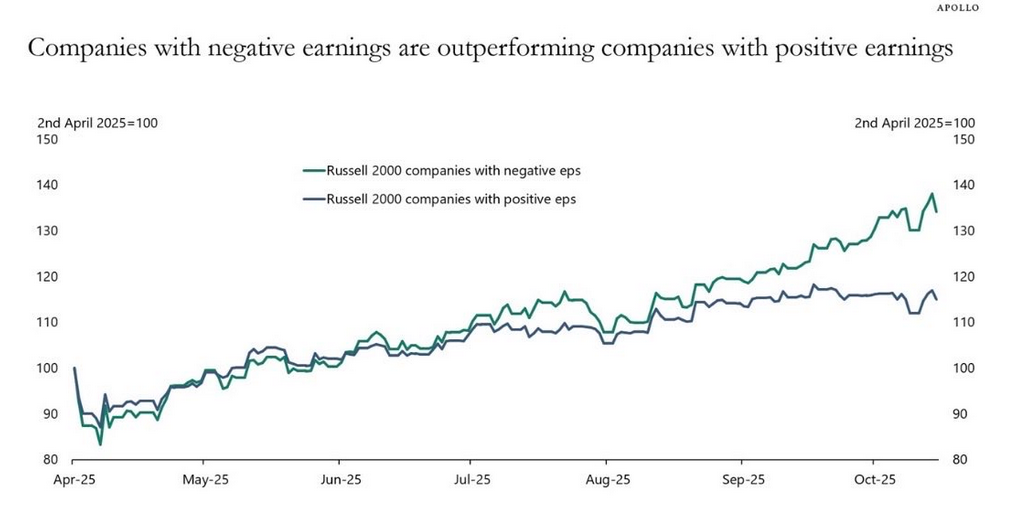

For Savita Subramanian, Bank of America Merrill Lynch’s head of U.S. equity and quantitative strategy, signals that investors aren’t paying much attention to earnings is another sign that the global rally may soon run out of steam. For the first time since the mid-2000s, companies that outperformed analysts’ profit and sales estimates across 11 sectors saw no reward from investors, according to her research.

“This lack of a reaction could be another late-cycle signal, suggesting expectations and positioning already more than reflect good results/guidance,” Subramanian wrote in a note earlier this month

We noticed this too. Companies that beat earnings estimates are not, as a group, rising after reporting. What does it mean? I looked at the effect of earnings on stock prices when I was revamping our investment process two years ago and what I found was that the correlation between earnings and stock prices in the short term is tenuous at best. Dividends and expectations about dividends are actually a much better indicator for future stock prices.

Earnings revisions – changes in expectations at the company level – are a fair indicator of future stock performance but what it really tells you about is momentum. Price momentum is almost completely explained by earnings momentum. So all Bank America is really telling us is that momentum isn’t as big a factor. Does that mean the market is headed for a fall? Maybe but momentum often waxes and wanes, even during bull markets. I would also point out that investors didn’t pay a lot of attention to earnings when they were going nowhere either. Earnings stagnated from Q2 2012 to Q1 2015 and investors had no problem pushing stocks up. Dividends, on the other hand, marched steadily higher during that time.

Ok, what about this bit from Oxford Economics:

Well that might mean something and the chart in the article sure looks ominous: If I felt like it, I could show you probably a dozen data charts from the last few years that looked just as ominous, showing things that have never happened before without an ensuing recession. And yet, we still aren’t in recession. What does that mean? To me it means this is one odd duck of an expansion and you better not be relying on one thing to make your recession call. |

US Real Gross Corporate, 1951 - 2017 |

Continuing:

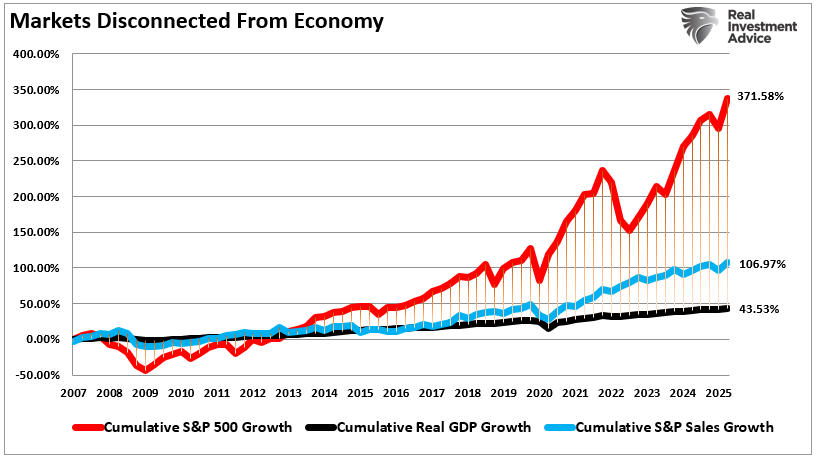

The thinking goes that a classic late-cycle expansion — an economy with full employment and slowing momentum — tends to see a decline in corporate profit margins. The U.S. is in the mature stage of the cycle — 80 percent of completion since the last trough — based on margin patterns going back to the 1950s, according to Societe Generale SA

There is no indication at all that margins are falling. S&P 500 operating margins peaked at 10.10% in Q3 2014 and fell to 7.98% by Q4 2015. But Q2 2017 margins are estimated so far at 10.22%. Last I checked 10.22% is > 10.10%. Full employment? The U-6 measure of unemployment is at 8.6%. That is still well above the rate in 2006 and 2000 so I don’t see this as full employment. Profit margins are mean reverting but they are also, at best, a coincident indicator. And not predictive of stock market outcomes. Margins – defined more broadly as corporate profits as a % of GDP – fell during the first half of the 1980s at the start of one of the greatest bull markets in history. They also peaked in 1997 and fell until 2000 during which time the stock market basically went straight up. What margins do seem to respond to is the value of the dollar. Margins tend to fall when the dollar is rising and rise when the dollar is falling. I would just point out that the dollar appears to be falling right now.

HSBC offers this:

After concluding credit markets are overheated, HSBC’s global head of fixed-income research, Steven Major, told clients to cut holdings of European corporate bonds earlier this month. Premiums fail to compensate investors for the prospect of capital losses, liquidity risks and an increase in volatility, according to Major.

I actually don’t disagree with that analysis but it isn’t exactly news. You could have said the same thing last year.

The weakest of the quotes in the article comes, not surprisingly in my opinion, from Citi:

Citigroup analysts also say markets are on the cusp of entering a late-cycle peak before a recession that pushes stocks and bonds into a bear market.

Spreads may widen in the coming months thanks to declining central-bank stimulus and as investors fret over elevated corporate leverage, they write. But, equities are likely to rally further partly due to buybacks, the strategists conclude.

“Bubbles are common in these aging equity bull markets,” Citigroup analysts led by Robert Buckland said in a note Friday.

Okay, so spreads might widen and stocks will go up anyway? Oooookay Citi. Thanks for the tip.

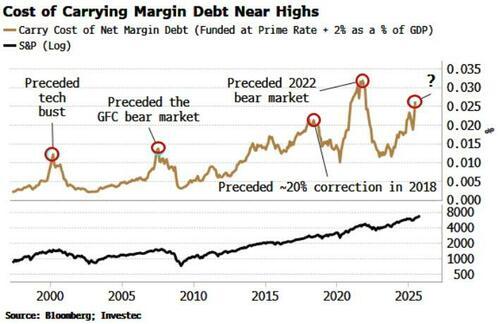

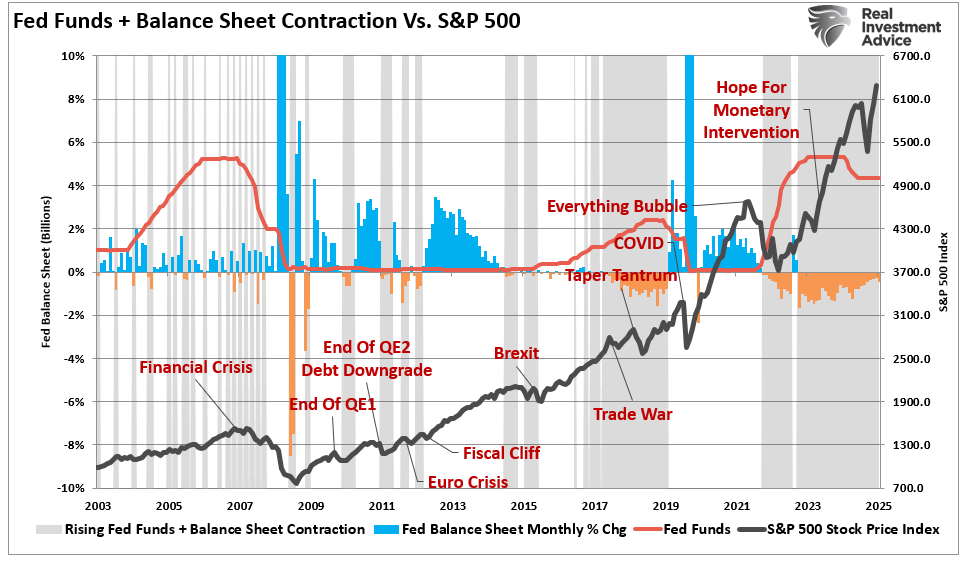

This has been one of the strangest business cycles on record. We’ve seen numerous indicators at levels or rates of change that have, in the past, only been associated with recession. And yet, we aren’t in recession. I’ve spent hundreds of hours reading academic research on how to predict recessions and there are only two indicators that have any predictive power – the yield curve and credit spreads. Almost any other indicator, by itself, is mere noise. They can be useful as confirming signals and for micro information but not as business cycle indicators.

An aggregate of economic data can also be useful. We monitor the Chicago Fed National Activity index because it has been accurate at identifying recessions in the past. And that is an important point. We don’t believe you need to predict when the next recession will come but merely identify it as it is happening. If you can do that you’ll be way ahead of any of these Wall Street banks.

These analysts may be right and I tend to think we are late in the cycle too. But you have to think about what that means. The article cited one analyst as saying that we are about 80% through the current cycle. Some simple math might be of assistance here. Let’s assume that analyst is right. The trough of the last recession was June of 2009 so this expansion is, so far, 8 years old. If we are at the 80% point, we are still 2 years away from recession. A lot can change in 2 years. Is this really useful information?

I don’t know if we are on the verge of recession but the best indicators of it are giving no warning right now. The yield curve is not acting in any way as if recession is near. Credit spreads, as I noted above, haven’t even moved 10% wider yet. The CFNAI 3 month moving average is -0.05, well above the -0.7 level associated with the onset of recession. I’m not saying everything with the economy is wonderful. If you read this blog regularly you know we don’t believe that. But I think you need to use indicators that have proven themselves useful in the past. The data points mentioned in the article are interesting but much more noise than signal.

Tags: Business Cycle,corporate profits,credit,earnings,economy,Markets,nber,newslettersent,recession