|

|

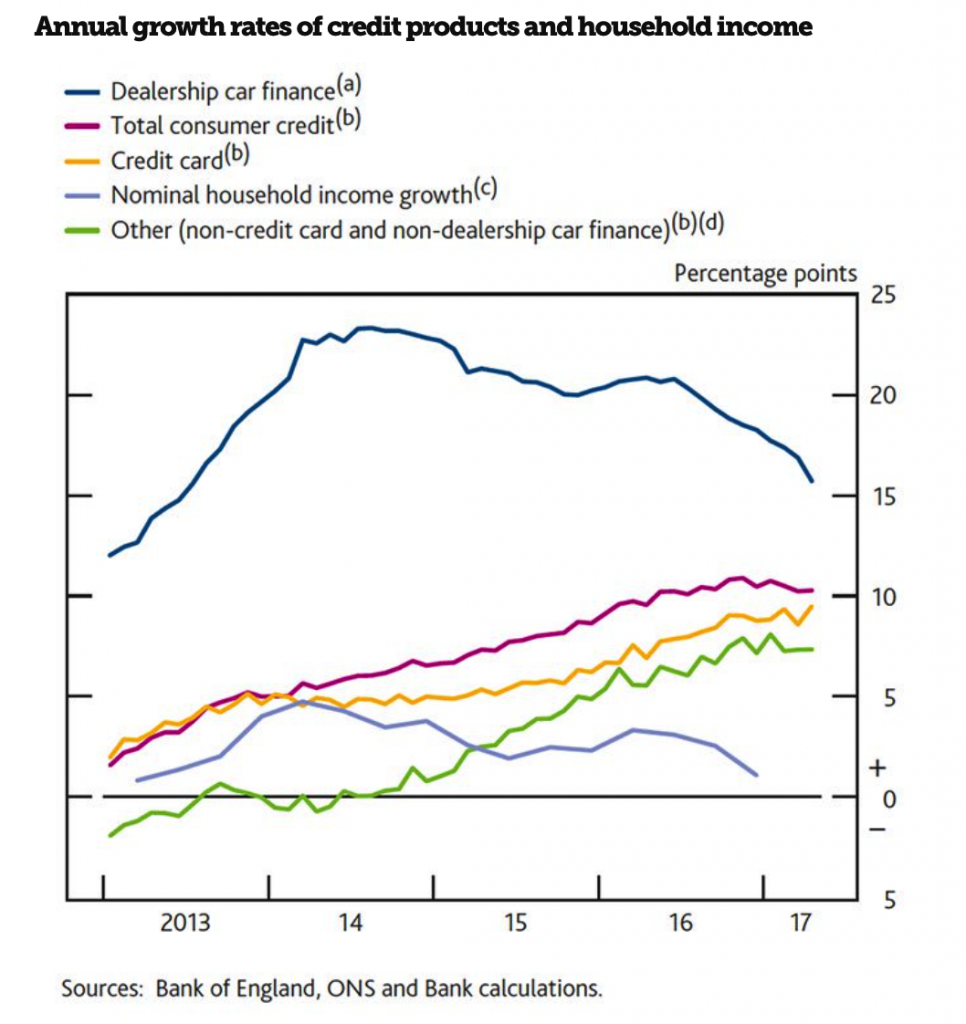

Editor: Mark O’ByrneWhy UK household debt will cause the next crisis “Household debt is good in moderation,” Alex Brazier, executive director of financial stability at the Bank of England (BoE), told financial risk specialists earlier this week. But, it “can be dangerous in excess.” The problem with ‘in moderation’ is that no-one knows what a moderate measure of something is until they have had too much of it. Sub prime borrowers in the U.S. and property buyers in Ireland and the UK did not know they would contribute to a global debt crisis. Central bankers in Germany in the early 1920s and more recently in Zimbabwe never thought they were doing something that would be as detrimental as it ultimately was. The same may go for levels of debt in western countries today and indeed the QE schemes and modern monetary experiments of western central banks. And, a moderate measure of something can be too much or too little from one person (or economy) to the next. For example, four glasses of wine for me are too much, for my Glaswegian cousin it is merely an aperitif. We only discover what is too much when ‘oh just one more’ happens time and time again. Another example, two credit cards are too much for me to manage, for my mother (a demon in money-management) it is fine. What about when it is two credit cards and a car loan and a mortgage? Is that too much debt for one household? Who knows, it depends on the household. Brazier believes that we are now on the brink of household debt being in excess and therefore dangerous. Why? Because we are seeing a 10% yoy increase in car loans, credit card balances and personal loans. This is due to a “spiral of complacency” from lenders who are offering cheap, easily available credit to households which have only seen their incomes rise by 1.5% over the same time period. This is something we have talked about previously. Brazier’s comments made headlines and rightly so. Personal debt in the UK is almost certainly already in excess and may well be the catalyst to the next financial crisis. As Brazier himself acknowledged, household debt can be dangerous ‘to borrowers, lenders and, most importantly from our perspective, everyone else in the economy.’ Yet again, something that was supposed to be in moderation has tipped the scales of balance towards obesity thanks to a nation that has gorged itself on cheap credit, all fed to them by the feeder banks and lenders. |

Credit Card Lending to Individuals, 2007 - 2017(see more posts on credit cards, ) |

The Spiral of ComplacencyThere are three main areas of concern for the Bank of England:

Understandably household debt can have a significant impact on the economy. Those with high loan-to-income mortgages will cut spending should interest rats rise or incomes fail to. Personal loans and high levels of consumer credit make banks vulnerable during downturn, should borrowers default. What has lead to this ‘spiral of complacency’ from lenders and banks? Brazier expressed concern that the recent period of growth combined with low interest rates may have caused banks to relax their lending rules: “The spiral continues, and borrowers rack up more and more debt. Lending standards can go from responsible to reckless very quickly.” Low interest rates are certainly one of the key issues. Debt charities believe one of the leading drivers of rising personal debt levels is that lenders have been forced to fight for business during a time record-low interest rates, so competition has become increasingly fierce. Many lenders now offer ‘zero-rate’ periods where no interest is due on balance transfers. We have all seen deals for credit cards that offer up to 43 months of interest-free balance transfers, or up to 31 months of interest-free spending. This, says debt charities, encourage borrowers to live beyond their means. In May 2017 net lending to individuals by UK banks and building societies rose by £173 million a day. In that one month net mortgage lending rose by £3.5 billion and consumer credit by £1.7 billion. No-one really knows what will happen when rates are increased (which they will be) and borrowers can no longer manage their debt. Of course lenders have been profiting from rising debt levels as borrowers take so long to pay off their debt that they pay a lot of interest. But, borrowers aren’t making much of a dent in the principal amount they have borrowed. When the next recession hits lenders will face losses of billions of pounds due to those borrowers who cannot afford to pay back their debts. |

Growth Rates of Credit Products and Household Income, 2012 - 2017(see more posts on Bank of England, credit cards, household income, ) |

How bad is the personal debt crisis in the UK?

Pretty bad. To look at the data one might feel as though much of British society is drowning in a sea of personal debt. The sea is filled with credit cards, overdrafts, hire purchase and other high-cost credit.

The UK Cards Association states that there are about 64m credit cards currently in use. These hold about £68 billion of debt, according to the BoE. Of these 64m, there are 3.3m (according to the FCA) who are struggling with 3.3m “persistent” credit card debts, defined as people who pay more in interest and charges than they do repaying their borrowings over an 18-month period.

Interest on loans is a serious and expensive problem. The Money Charity estimates that the UK’s total interest repayments on personal debt over the last twelve months would have been £50bn, or £187m per day, or £1,845 per household each year just on servicing the debt.

Credit card debt is just one element of the UK’s debt problems. According to the Money Charity, as of July 2017 there was £199.7bn of unsecured debt in the UK. In total, £1.537 trillion was owed at the end of May 2017, that’s an extra £949.96 per adult since May 2016.

Car loans, one of Brazier’s principle concerns, now fund almost four in five new car purchases – up from one in five in 2006.

In terms of households, the overall level of household debt grows every month. The Money Charity estimates that in May 2016 the average total household debt (including mortgages) was £56,731, and increase of nearly £200 from the previous month. Per adult, state the charity, this means that there is an average debt of £29,698 or 135% of average earnings.

This is likely to get worse.

StepChange, the country’s leading debt advice charity, saw a further 600,000 people seek financial help in 2016. The body has offered stark warnings about Britains indebted families estimating that 8.8m people have turned to credit to pay for everyday household expenses over the past year. £3,858 is the level of consumer credit borrowing on average, per individual.

The Office for Budget Responsibility estimates that household debt will reach £2,322 trillion by Q1 2022. Assuming the number of households remains the same, average debt per household will be £86,001 by 2022.

Of the 8.8m who have turned to credit, more than half were employed and 41% in full-time work. This brings us to the point that debt levels are growing not because of unemployment but because the majority of Britons literally cannot earn enough to survive in this inflationary environment with a sharp rise in costs for renters and home buyers and a stealth shrinkflation and a creeping inflation.

Should households continue to just make minimum repayments then it will take nearly 26 years for credit card debts to be cleared – should average rates remain the same.

Do the Authorities Even Care?

Recently we told you about demands from the PRA to banks (see link below) that they increase their countercyclical capital buffers (capital held to increase resilience to risks). They have asked for evidence that banks are doing so, so concerned are the regulators that their concerns over household lending are not being addressed.

Earlier this year the FCA launched an investigation into credit card lending. The outcome was a host of proposed rules to help those struggling with credit card debt, one of which was the idea to order companies to help customers “by reducing, waiving or cancelling any interest or charges” for borrowers struggling to repay their debts.

In Q1 of this year £530 million (of which £394 million) in credit card debt was written off, a daily write off of £7 million by UK banks and building societies. How sustainable is this?

The regulators aren’t the only ones looking for solutions.

Clearly the borrowers themselves are concerned about their levels of personal debt. Every day 248 people are declared insolvent or bankrupt. This is something which politicians are trying to use as political leverage.

During the recent general election both Labour and Conservative manifestos pledged to adopt ‘breathing space’ policies which would see payments for distressed borrowers frozen and replaced by a “statutory payment plan”. The idea is to help serious debtors get out of the red in a manageable way.

These are all very nice for the borrower but what about the banks and lenders who will be impacted by this?

Personal debt hugely affects the housing market, not just directly by the mortgage holder but also in the rental market.

How do landlords survive if their tenants cannot afford to cover the rent?

It will soon be even harder for them to take serious measures if the Conservatives follow through with their plan to improve consumer protections for tenants. Good for the tenants, tougher for landlords trying to cover mortgage repayments with no income.

Conclusion – Too little, Too late

Whilst the point remains the same – households are borrowing at a faster rate than incomes are increasing – the truth is that despite Brazier’s claims household incomes in real terms have not increased.

Real inflation rates are much higher than official measures and households continue to be shafted by shrinkflation, low interest rates and increased living costs.

On average it costs £30.31 to raise a child, this is nearly half the average daily income. There is hardly any more (or incentive) for households to save for tougher times.

The result? Households are living beyond their means.

Prior to the financial crisis the media liked to point fingers at irresponsible borrowers. In truth, the situation remains no different to what life was really like before the crisis, households living beyond their means thanks to an inflationary environment and lenders preying on the weak for maximum profit.

The numbers speak for themselves, there is little let-up on the side of the lenders when it comes to encouraging loans. The households have little means to survive without cheap credit when the cost of living remains high.

So, when Brazier is issuing a warning to the banks, along with the regulators and politicians, we wonder if it is too little too late.

Banks and lenders have been here before and they continue as though this is all new. As Brazier himself said, back in 2007:

“Banks – and their regulators – were blind to the basic fact that more debt meant greater risk of loss”.

Who on earth is running a bank (or anything that involves basic accounting) and is ‘blind’ to this scenario?

Most bank managers it seems, but they need to wake up asap, says Brazier:

“[In 2007] complacency gave way to crisis. Companies and households were unable to refinance their debts. The result was economic disaster.”

Savers and prudent spenders can do very little about the current mess of things. All we can do is protect our own finances. Even if there are financial institutions who are heeding such warning signs it is unlikely to make much difference. The level of debt in the financial system in the UK and most western countries is completely unsustainable.

For the majority of savers this means personal finances and savings held in deposit accounts are at risk from bank bail-ins. Bank bail-ins and negative rates seem increasingly inevitable.

Make sure your savings are not exposed to these risks by diversifying into counterparty risk free gold and silver coins and bars for insured delivery and secure storage.

Full story here Are you the author? Previous post See more for Next postTags: Bank of England,credit cards,Daily Market Update,household income,newslettersent