(I have been sick with pneumonia but am just about back. I expect to resume my commentary tomorrow. Here is my overdue monthly column for a Chinese paper. Thanks to everyone for their support.)

Conspiracy theories have run amok. After several years of claiming countries were engaged in currency wars, or attempts to drive their currencies down to achieve export advantage, many reporters and analysts announced a volte-face. At the late February G20 meeting in Shanghai, a secret accord has been concocted that declares a truce in this made up war.

The main idea had been that a rising dollar and falling currencies had become destabilizing. Officials recognizing this changed tact. The ECB and BOJ, for example, would not seek to weaken their currencies, and the Federal Reserve, for its part, would take its foot off the monetary brake that it had tapped on at the end of last year.

There are two main problems with this popular narrative. The theory and the facts.

It is true that the floating exchange rate regime lends its self to abuse. Countries can pursue beggar-thy-neighbor policies that steal the aggregate demand of another country by directly seeking currency devaluation to boost exports.

Yet the claims of a currency war are misplaced. What is misunderstood goes right to the heart of global governance issues.

There has been an arms control agreement in the foreign exchange. At both the G7 and G20 levels, there has been an endorsement that foreign exchange prices are best left to the markets, except in unusual circumstances. The agreement is enforced like other arms control agreements. Trust but verify.

When a country ventures too close to violation, it is called out. Recall, that as Japanese Prime Minister Abe was campaigning in late 2012, he and other Japanese politicians were perceived as attempting to manipulate the yen’s value too directly and were chastened by the other G7 members. A new pledge was demanded that committed the Abe government to the arms control agreement.

The US Treasury Department also acts as a monitor. Required by Congress, the US Treasury provides semi-annual updates of the international economy and the foreign exchange market. It has been more than a decade since it accused any country of manipulating the foreign exchange market.

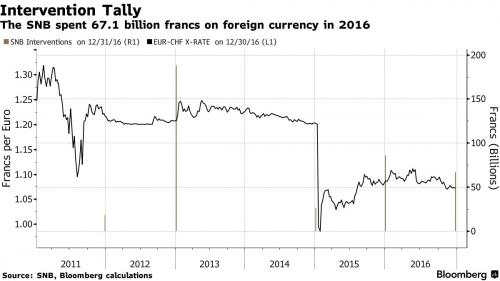

Nevertheless, it is has been critical of some countries for too frequent intervention, or the lack of transparency in its operations. South Korea, Taiwan, and China all come to mind. It has been critical of some countries, like Australia, for its verbal intervention.

At the same time, the rules of engagement and the US Treasury recognize the distinction between manipulating currencies and manipulating interest rates. It is not market fundamentalism here; it is a pragmatic differentiation. Beggar-thy-neighbor competitive currency devaluation is a zero-sum exercise. It does not add to growth. It forces others to do the same, leading to a downward spiral.

Manipulating interest rates boosts aggregate demand. It may encourage others to cut interest rates as well, boosting their demand as well. It can be a non-zero-sum exercise. Easier monetary policy can lead to currency depreciation, but this is not always the case. Investors can recall many examples of a central bank cutting interest rates, and sometimes by surprise, that has produced a counter-intuitive currency appreciation. The recent unorthodox easing by the European Central Bank and the Bank of Japan are timely examples, but there are countless others.

With all due respect, the early warning system of violations in the arms control agreement in the foreign exchange agreement are not journalists or economists, but other policymakers. And such calls have been practically non-existent in recent months. Even the fears that the PBOC was seeking a larger devaluation of the yuan ebbed. The yuan strengthened slightly in Q1 16.

There is no secret truce because there was no war in the first place. The historic agreements in the foreign exchange market, like the Plaza Agreement itself in 1985 was not secret. Officials wanted to ensure that investors and other policymakers were well aware of their intentions. Why would an accord struck in Shanghai be secret? The only advantage is that it requires a lesser burden of evidence by its proponents.

There was not need for a secret or overt agreement to stop the dollar from rising against the euro or yen. In fact, the euro’s cyclical low against the dollar was recorded a year ago in March 2015 near $1.0460. The dollar had peaked against the yen in June 2015 a little below JPY126.00. Nor does it seem credible that the US, which still argues that the yuan is fundamentally undervalued, or Europe, which has recently initiated anti-dumping complaints against Chinese steel producers, would sign on a secret agreement that takes pressure of China.

To the contrary. Rather than the recent appreciation of the euro and yen being the desired results of an secret agreement struck at the Shanghai G20 meeting, comments from European and Japanese officials indicate they have been as surprised and frustrated with the price action as have many investors. The Federal Reserve has backed away from the four rate hikes that at the end of last year that it thought reasonable for this year, but surely weak Q4 15 and what appears to be disappointing Q1 16 growth rather than a secret agreement lies at the roots.

Occam’s razor dictates that the simpler solution is preferable. Entities should not be multiplied needlessly. Senior officials have denied the existence of a currency war. They have denied a secret truce. There is no evidence that the G7 or G20 have abandoned the best practice as it has emerged since the Plaza and Louvre Agreements that currency values are best determined by the markets.

The greater the claims, the greater the evidence necessary. Investors should not be distracted from their strategies by talk of secret cabals and agreements. Foreign exchange waters are treacherous even in the best of times, and they are as frustrating and imponderable for policymakers as much as for investors.

Tags: currency war