(Originally written in 2012, arguments still valid today, some charts are updated)

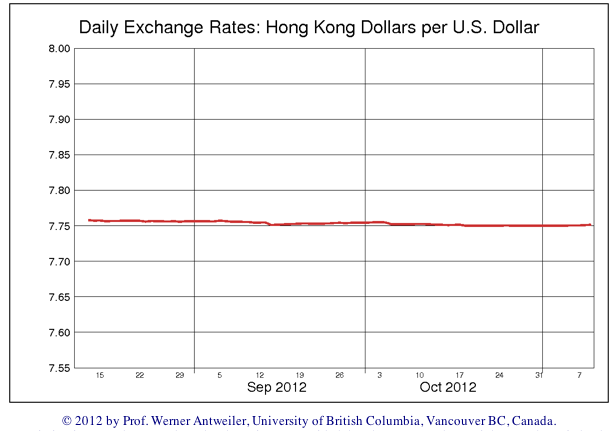

The SNB will not be able to realize a fixed currency peg against the euro over the long-term. One example of a fixed peg is Hong Kong. This country has a so-called “currency board” against the US dollar. The exchange rate between the US dollar and Hong Kong dollar is fixed. Hong Kong has managed to maintain this peg for years, even if recently it was under pressure.

Switzerland cannot imitate Hong Kong for the following reasons:

- Taxes: Having a real estate tax only for foreigners like in Hong Kong will not help. It is incompatible with the Swiss-EU bilateral agreements and can be circumvented quite easily. A citizen of the EU could rent a flat for a small period and is an official resident of Switzerland. He is allowed to buy a home. In order to change this, Switzerland would need to exit from the bilateral agreements.

- The currency reserves of Hong Kong did not rise that much unlike the Swiss did. They have increased by 10% since 2011, but the ones for the SNB by 50%.

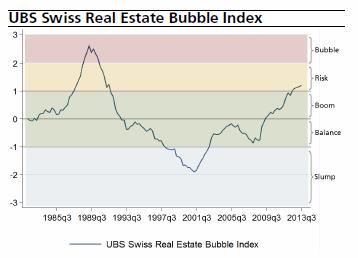

Hong Kong’s real estate market seems to be clearly overvalued. But in Switzerland it is only situated in the initial risk phase. Switzerland seems to be able to attract foreign capital to be invested in real estate, with the long-term result that inflation goes up.

Hong Kong’s real estate market seems to be clearly overvalued. But in Switzerland it is only situated in the initial risk phase. Switzerland seems to be able to attract foreign capital to be invested in real estate, with the long-term result that inflation goes up.- Hong Kong does not have big safe haven attractiveness like Switzerland, because it is dominated by the authoritarian state China.

- The main important point is the following: Currency boards make sense for countries that have higher inflation than the target country. In 1997 Bulgaria introduced a currency board against the ECU/Euro, a region with lower inflation and Hong Kong one against the US dollar. Jim Rogers said recently that he cannot imagine Switzerland becoming a “new Bulgaria”. The consequence would be similarly to Bulgaria: Switzerland would have at least the same inflation and the same interest rates as the euro zone. This would make Switzerland less attractive for investors and weaken Swiss banks, as Oswald Grübel already said last year. Like Thomas Jordan asserted in 1999, over the long-term Swiss companies would need to borrow at a higher rate and lose their competitive advantage.

- Because of this difference, the peg of the HK dollar against the US dollar may remain for years but the EUR/CHF peg cannot. Hong Kong still has smaller wages than the United States; therefore, it is able to counter higher wage and inflation increases with a rise in productivity. Similarly, Bulgaria has far smaller wages than the eurozone.

- Switzerland, however, has higher wages and higher productivity thanks to big structural advantages, lower taxes and sees immigration of highly qualified personnel from the euro zone. The European periphery needs to reduce wages to become competitive again. Therefore inflation in Switzerland could be bigger than in these European countries, once the deflationary effects of the “strong franc” have washed out.

- If the floor is maintained, then the Swiss might obtain a similar inflation rate as Germany (currently 2.1%) over the long-term; their inflation baskets are quite similar. Whereas German salaries are poised to rise more quickly than the Swiss ones, monetary expansion and increase of real estate prices are far higher in Switzerland. Since the Swiss seem to be less reluctant to spend (see here and here) than the Germans, it is possible that in a couple of years Swiss inflation will be higher than in Germany.

We think that the SNB will exit the peg in one to three years. When depends on the state of the global economy, the more the global economy improves, the earlier it happens because Switzerland will exhibit higher inflation. If the United States leads the global recovery, then the EUR/CHF rate could remain above 1.20 for some time.

Both countries, Switzerland and maybe one day even Hong Kong will imitate Singapore, that follows a so-called “basket, band and crawl managed float (BBC float)”.

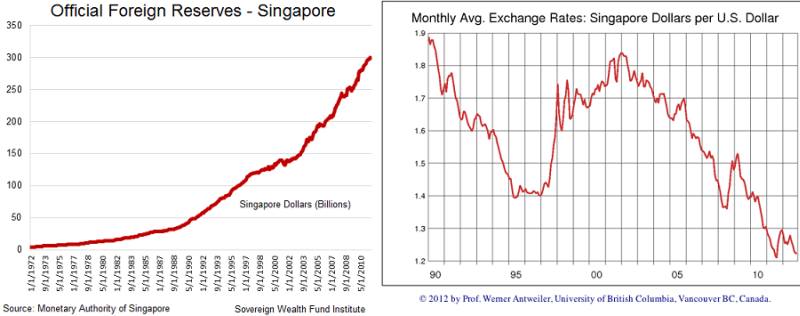

The Singapore dollar is managed against an undisclosed basket of currencies of its main trading partners and competitors. The exchange rate floats within a set policy band, which lets the currency crawl up or down instead of being subject to sharp fluctuations. The Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) has said the BBC policy has given it flexibility in responding to changes in both local and global conditions to maintain export competitiveness and control inflation. source

Similarly to the People’s Bank of China (PBoC), the MAS increases its reserves during “currency reserve accumulation phases” thanks to current account surpluses and capital inflows.

Both the MAS and the PBoC combat wage increases and internal inflation with a controlled appreciation of their currency (the currency “crawls up”). In order to do this, they sell foreign currency reserves and realize FX losses. During weak economic phases – the last long one during the Asia crisis in 1998 – they might also allow the currency to “crawl down” and they realize FX gains.

Given that weak phases do not happen very often – these central banks must obtain sufficient profit during the “currency reserve accumulation phases” with income and valuation gains on their assets. In order to improve profits the MAS possesses a Sovereign Wealth Fund (SWF): the Government of Singapore Investment Corporation (GIC) manages 100 billion dollars, 30% of the Singaporean reserves. An SWF is a model that had been excluded by the SNB till now. The Chinese SWF, called “China Investment Company, CIC”, looks after 12% of the total Chinese reserves of 3.3 billion dollars and goes more risks than the State Administration of Foreign Assets (“SAFE”), that essentially holds government bonds. The SNB has increased the equity quota to 12% in the third quarter 2012. As opposed to an SWF, the Swiss follow a passive investment strategy.

See more for