The short version:

- Via quantitative easing central banks of QE countries push up prices of risky assets.

- The effect spills over into (risky) assets in Emerging Markets (EM). The currencies of QE countries depreciate. With capital inflows, wages in EM rise excessively, while salaries in QE countries nearly stagnate.

- The relative adjustment of wages increase relative competitiveness of QE countries.

- Thanks to the relative rise of competitiveness and to an inversion of capital flows from EM to the U.S., American home prices recover since 2012, U.S. manufacturing recovers since 2013.

- A secondary effect during the spillover phase, during a phase of high inflation phase in summer 2011, was the so-called euro crisis.

(written in Summer 2013 with some updates later)

Monetary and fiscal policy in the Euro crisis: The Balance of Payments Crisis

- The euro zone crisis is a balance of payments crisis.1

- Balance of payments crises (“BoP” crises) often appear during inflationary periods – when inflation in the leading country of the global monetary system, the United States, is high. During inflationary periods, during the weak period of the credit cycle, bond yields of crisis countries explode, credit spreads increase. The crisis often disappears with disinflation, lower interest rates and higher risk-appetite. The disinflation happens typically when oil prices fall and the U.S. economy subsequently improves. With the next “inflation leg” they reappear.

One historical example is Latin America in the 1980s. With the Washington Consensus measures, an initial improvement happened. None the, less these nations ended up in a lost decade. - At the height of a balance of payments crisis, typically a banking crisis appears.

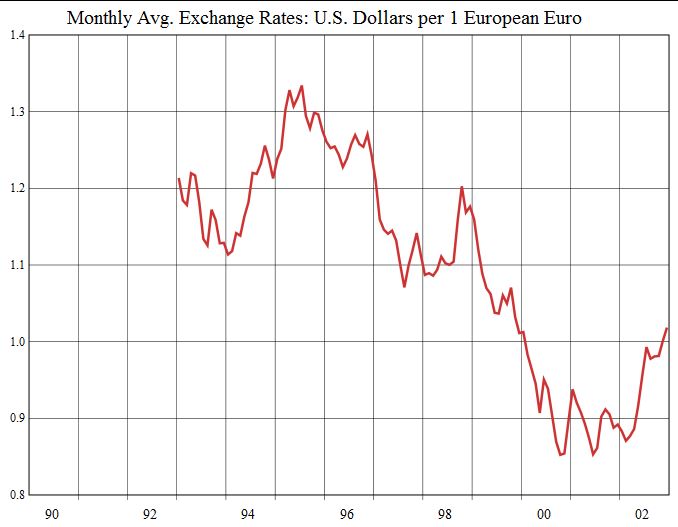

- During a BoP crisis, the concerned currency typically depreciates and supports exports. While at the beginning of the European BoP crisis the euro was still strong (=1. 40 USD), while a euro under 1.30$ support European exports.

- German consumption must increase in order to solve the euro crisis. It should not rise too much, Germany should not overheat, because this could cause inflation and a new balance of payments crisis (similar to the EMS crisis in 1992 that started with the German reunification and high spending).

- Restoring the credit channels is essential

via Carmen Reinhart’s letter to Paul Krugman: On the policy response to this sad state of affairs, we stress that restoring the credit channel is essential for sustained growth, and this is why there is a need to write off senior bank debt in many countries. Furthermore, there is no reason why the ECB should buy only sovereign debt-purchases of senior bank debt along the lines of the US Federal Reserve’s purchases of mortgage-backed securities would be instrumental in rekindling credit and working capital for firms. We don’t see your attraction to fiscal largesse as a substitute. Periphery Europe cannot afford it and for Germany, which can afford it, fiscal expansion would be procyclical. Any overheating in Germany would exert pressure on the ECB to maintain a tighter monetary policy, backtracking some of the progress made by Mario Draghi. A better use of Germany’s balance sheet strength would be to agree on faster and bigger haircuts for the periphery, and to support significantly more expansionary monetary policy by the ECB.

- There is no monetary policy way to force Germans to consume and German companies to invest. Germans are too risk-averse, especially given the recent issues and the falling demand from major trading partners. An ECB “commitment to 4% inflation” by Market Monetarists would not raise German consumption; they would rather save in real estate, gold and into Swiss francs.

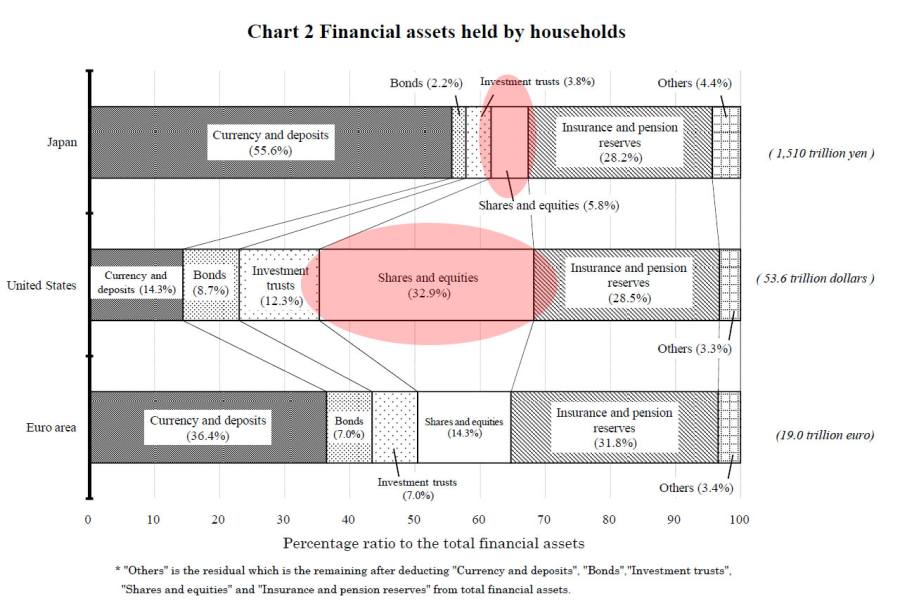

- Whether fiscal or monetary policy is applied, depends on the mentality. You cannot force a Japanese or a German to spend. They are rather risk-averse and have a higher savings rate (see the composition of their portfolios above). In the Japanese and German case, fiscal policy was preferred for years. With Japanese aging, the savings rate has shrunk, hence fiscal policy must be tightened again. In the U.S. monetary policy, however, is more successful.

- A balance of payments crisis cannot be solved by consumer spending in the weak countries; they must export themselves out of the recession (see also Washington Consensus).

Evidence (via VoxEU) shows that this has been successful, albeit mostly due to a (possibly temporary) increase of the savings rate. Another reason for the BoP improvements is the lower oil price, that depreciated with lower spending and investments in the EU and with a cyclical slowing in the emerging markets. Improvements in the trade with Germany are not sufficient yet. - In France, Italy or Spain, home prices are overvalued compared to income or compared to German prices. The reason was the sudden decrease in mortgage rates for Spaniards or Italians with the euro introduction and the increase of housing supply with the German reunification. Particularly homes in Eastern Germany are often far cheaper than homes in Southern Europe (see also ECB household wealth reports).

At the latest, when interest rates start to rise again, home prices will decrease in the South and in France. They will revert versus the German price trend. Falling population and housing oversupply may help to anticipate this tendency. A balance sheet recession might loom in these countries, because people might prefer to reduce debt instead of spending. - Confronted with the BoP crisis, European leaders took the right measures. The total EU-17 trade surplus has risen to a record-high, because Germans are still reluctant to spend/invest and Italians and Spaniards improved their trade. Rising unemployment is a collateral damage related to the solution of the BoP crisis and highly related to the increase in the savings rate. Unfortunately, but logically they demanded from Italy, Spain or France to reduce debt , however Implicitly to move into a balance sheet recession.

- Fiscal spending in countries like Italy, Spain or France is less efficient than in countries like Japan or Germany. The success of Brazil, Mexico, Angola or Chile that all have low tax rates shows that fiscal spending should be limited in these latin/romanic countries (Evidence on VoxEU).

- Allowing higher fiscal spending (e.g. Blanchard: Fiscal consolidation at which speed?) will not be the final solution for Italy, Spain or France. Competitiveness must be increased. None the less, the austerity seems to be excessive, especially following the upcoming deflationary scenario.

- Germans should do some moderate fiscal spending instead, e.g. improve infrastructure in Germany. Italian, Spanish or French firms might get the deal to do the work.

- If Italy, Spain and France do not solve their competitiveness problem with (relatively) lower wages, the euro crisis will go into another episode when inflation restarts.

- We think that they won’t solve them that quickly.

- This does not imply that the next episode of the euro crisis will be as strong as the one in 2011. Time heals all wounds, especially fear.

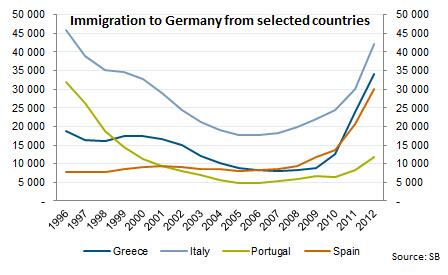

- Despite our skeptics, salaries in many weak countries are adjusting downwards, when employers are able to impose lower wages to new or even existing workers. This is positive for companies and stocks. On the other side, brain-drain movements to Germany or Switzerland are increasing the difference of competitiveness between North and South.

- Italy, Spain and also France might eventually leave the euro zone in order to be able to use loose monetary policy tools against the deflation in the euro zone while fiscal spending is already at its limit. This exit will not happen very soon, but in a couple of years when higher inflation comes up.

Alternatively we could see a weaker euro, far too weak for Germany.

Monetary and fiscal policy in the United States

- The U.S. holds the world reserve currency. Therefore it can never experience a balance of payments crisis with the typical symptoms like high bond yields. It is the only country in the world that can solve its issues with spending, while the current account drives economic policy and central banks the rest of world, in particular the ones in EM.

- The financial crisis of 2008 was, nonetheless, the first and the only U.S. balance of payments crisis in this century. The excessive U.S. current account deficit was amplified by deficit spending based on overvalued home prices. Similarly as Brits, Americans will continue to reduce debt, they will remain in a sort of balance sheet recession (evidence NY Fed).

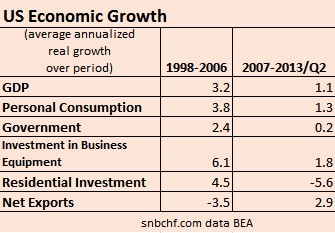

- The U.S. have a growth and a competitiveness problem. The growth issue can be solved either by monetary or by fiscal policy. But fiscal policy is currently not accepted by U.S. politicians.

- Monetary policy is quicker and more risky; with MBS part of QE3, it artificially sustains U.S. home prices. With any rate hike, the housing market may collapse again – remember the 1937 reccession. QE3 attracted “hot capital” to leave the emerging markets and Europe. Detailed data shows that in particular multi-family homes in centresa have risen in price. Hot capital targeted those.

- Over the long-term home prices are only able to rise in sync with income and GDP. They will most naturally fall again, once inflation restarts and when the Fed stops the stimulus – Robert Shiller: House Prices flat for next 10 years.

- As opposed to U.S. homes, U.S. stocks are able to participate in the stronger long-term GDP growth of emerging markets.

Balance of Payments Crisis and the Gold Standard

- During the gold standard, a balance of payments crisis was nearly impossible: central banks and governments fought gold drains with higher rates and austerity. Fiscal tightening, unemployment and finally lower wages improved relative competiveness and stopped the balance of payments crisis before it could show its typical symptoms.

- According to Murray Rothbard, British inflation and an overvalued pound dragged the U.S. into inflation in the 1920s and later into deflation. Finally the UK left the gold standard first. We follow that the UK had a BoP crisis. Due to trade barriers, BoP crisis countries could not export to get out of the crisis. The only way out was global deflation, called the Great Depression.

A Monetarist Approach: Did the Fed Cause the Euro Crisis with Excessive Monetary Easing?

The Fed always repeats the same mistakes and is not patient enough (Milton Friedman). TARF (Asset-based security purchases) and QE1 were good to remedy the Fed’s faults between the years 2002 and 2005.

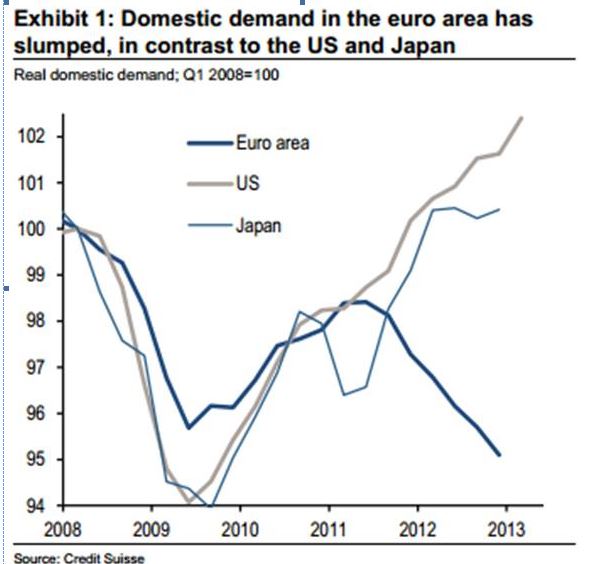

The Fed always repeats the same mistakes and is not patient enough (Milton Friedman). TARF (Asset-based security purchases) and QE1 were good to remedy the Fed’s faults between the years 2002 and 2005.- QE2 combined with the Chinese fiscal and monetary expansion of 2009/2010 was overdone and extremely risky. Even for the ECB it caused a so-called “spill-over effect” (ECB “spillover” paper).

For these risks the term “currency wars” was correct, because it created a lot superfluous investments, e.g. in real estate in emerging markets and excessive capacity in China. QE2 created excessive growth and subsequently high inflation in emerging markets. But it failed to improve the availability of credit in the United States, to quicken the weak phase of the U.S. credit cycle. Even more it topped in the S&P downgrade of the U.S. in September 2011. Due to the big growth differences between developing nations and the weak members of the euro zone, QE2 helped to increase required yields. This was essentially the reason for excessively high yields in the weak countries and therefore one reason for the balance of payments crisis in the euro zone. - QE3 is a measure to undo QE2 and its negative effects and it was necessary despite its risks. Effectively capital flows show that the funds are flowing back to the U.S. Without QE2 and QE3 we would have come back to the status of 2010 plus some years of slowly improving environment, but there we wouldn’t have seen the excesses during the euro crisis. Germans would be consuming far more, their fear would be less.

- The Fed must take movements in global money supply, as leading indicator, into account when taking measures. The coincident indicator PCE deflator is too late.

- Central banks’ overreaction cause currency movements, fundamentals do not. In the case of the U.S. sub prime crisis and in the 1970s these movements lasted even longer.

The current strengthening of the dollar is a temporary movement caused by some higher private spending and by investment flows to the U.S. The austerity in Europe and the cyclical slowing in emerging markets amplified by lower demand from Europe shows that the United States are currently the safest place to invest. Central banks and European austerity let the dollar appreciate. The dollar strength may take another year or two, due to self-fulling prophecies, possibly even more – “good economic data follows fund flows, more funds follow thanks to good economic data”.

The current strengthening of the dollar is a temporary movement caused by some higher private spending and by investment flows to the U.S. The austerity in Europe and the cyclical slowing in emerging markets amplified by lower demand from Europe shows that the United States are currently the safest place to invest. Central banks and European austerity let the dollar appreciate. The dollar strength may take another year or two, due to self-fulling prophecies, possibly even more – “good economic data follows fund flows, more funds follow thanks to good economic data”.- The U.S. has the world reserve currency, a small savings rate and a high dependency on oil prices that lifts production costs more than elsewhere. For these three reasons it will never solve its competitiveness issues.

- There is no technological or institutional development that could reason a stronger dollar like the PC (and the dot com bubble) of the 1990s. Even that dollar improvement episode was assisted by stronger demand for U.S. products triggered by emerging consumer demand from former communist nations and extreme fiscal spending with the German reunification until 1995. The German reversion into austerity in 1997 finally weakened the DM, the German economy and the euro. Euro introduction austerity and the Asia crisis did the rest. The euro fell to $0.85

Again strong investment flows to the U.S. sustained the dollar. The strong dollar in the 1980s was caused by Volcker’s high interest rates, dependency of emerging markets on U.S. funds and the oil glut. - Unlike the 1980s, low interest rates, the hunt for yield and their accumulation of reserves will permit emerging markets, especially Asia, to further narrow the gap to the developed world. The natural desire to increase income is higher when you are poor than when you have already achieved a certain standard of living, especially when this standard is a state-guarantee.

-

So far QE3 has successfully saved the world from a global crisis. The combination of U.S monetary expansion and fiscal austerity in Europe was a nearly perfect mix to fight the balance of payments crisis in the euro zone.

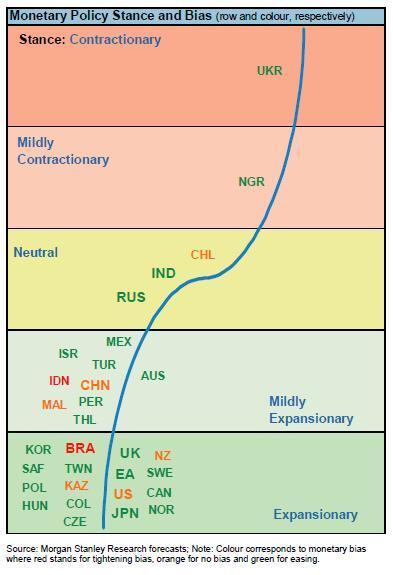

- But the QE3 policy response was possibly once again too strong and might end in higher U.S. inflation, given that – similarly as in 2009/2010 – many central banks are expanding. Fortunately the Chinese PBoC, the second most important central bank, has a tightening bias and cracks down its housing bubble and the overinvestment.

- The next balance of payments crisis will happen in emerging markets once the Fed removes the stimulus. Argentina is in the lead. Other emerging market economies with current account deficits and quickly rising wages like Turkey and Brazil might follow.

- Paul Krugman, 1979, ‘A model of balance-of-payments crises’. Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking 11, pp. 311-25. [↩]