Many people claim that “money printing” and increasing money supply does not create inflation, some even speak of the “inflation lie”. Effectively, higher money supply has not created high inflation in developed nations yet because many of them were in a balance sheet recession, a period when firms and individuals prefer to reduce debt instead of investing and spending.

Dan Kervick asserts in the New Economic Perspectives :

First: the Fed can’t even control broad money, because it can add to bank reserves and they just sit there; and money in turn bears little relationship to GDP. And in retrospect the same was true in the 1930s, so that Friedman’s claim that the Fed could easily have prevented the Great Depression now looks highly dubious.

There are three distinct issues to untangle here, which Krugman briefly compresses in his “soup to nuts” condemnation. …”monetary policy is not identical to central bank policy”. The central bank is a key participant in setting monetary policy, but does not unilaterally direct it. ..

A second issue, though, is whether any realistic combination of government policies can control the money supply. Bank lending in the aggregate, responding to the demand for credit, continually creates new deposits for willing borrowers. That in turn means an expansion of broad money. This growth in bank deposits results in a greater net demand placed upon the payment system for interbank settlements. The assets banks use to settle those payments are primarily their deposit balances at the Federal Reserve banks. So realistically, the central bank must accommodate most of this independent private sector activity in order to maintain stable interest rates and facilitate the smooth functioning of the payments system. As a result, the central bank makes the corresponding changes to the monetary base required to achieve these goals. It thus looks like the private sector is doing the real driving here: changes in private sector demand for credit and bank issuance of credit come first; changes in the monetary base follow along after. Government policies can certainly influence the private sector demand for credit, but they can’t control it. The central bank can regulate or modulate activity in the market for bank credit, but it can’t determine it.

And finally, even if the government could control the money supply, a third issue is whether that would be a particularly important and decisive thing to do. How many of the major macroeconomic issues concerning growth, employment, income distribution, financial stability and innovation really depend fundamentally on what is happening with the money supply?

Friedman’s Monetarist Cycle applied to Emerging and Developed Markets

In most Western economies the rational expectation reigns among people, that due to public and private debt and high unemployment, salary increases are impossible and more debt should be avoided. However, the situation in emerging markets is different. The huge money supply caused an inflationary period in emerging markets that just ended with an overheating in some of them.

The cyclical slowing in emerging markets is currently one reason for low inflation and rising stock prices in developed economies. Once wages in developed nations begin to rise, the later countries might repeat Friedman’s cycle. In the first inflation phase in emerging markets, inflation was still relatively low for Americans and Europeans, but in the next cycle, high inflation might arrive at home. Big inflation differences between Germany and the rest could split the euro zone.

Global money supply

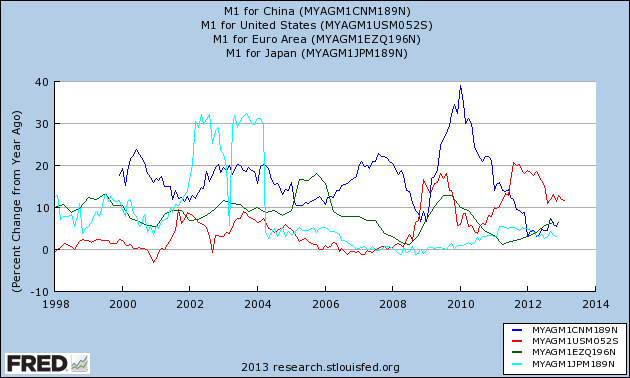

The following graph represents the money supply M1, a measurement of liquidity in banks, in the major economies United States (in red), China (dark blue), Eurozone (green) and Japan (light blue). These money supply numbers are often lower than the monetary base, the basis for multiplying money supply created by central banks.

Between 2012 and Mid 2013, American, and even European, money supply growth is overtaking money supply growth in China; Chinese authorities are still very hawkish and want to stop inflation and real estate price increases, investment inflows into China slowed.

Between 2012 and Mid 2013, American, and even European, money supply growth is overtaking money supply growth in China; Chinese authorities are still very hawkish and want to stop inflation and real estate price increases, investment inflows into China slowed.

Friedman’s monetarist business cycle

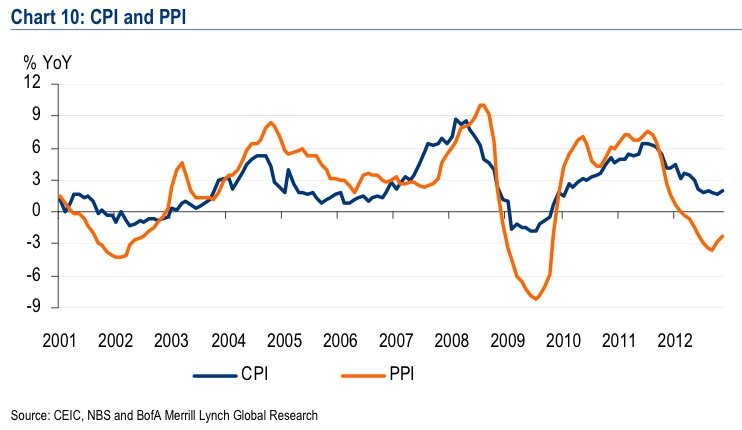

According to Milton Friedman, monetary action takes a longer time to affect the price level. He was proven right recently. The excessive increase of money in 2009/2010 was followed by strong inflation in Summer 2011. While inflation still follows money supply in emerging markets with a certain delay, the Fed maintains that the relationship has become weaker in developed economies.

In his famous essay, “The role of monetary policy” in the American Economic, Friedman describes the monetarist business cycle, or better excesses of a sound business cycle, as follows:

- The end of the previous cycle, often from an inflationary period (sometimes a period of financial distress) followed by a sound recovery.

- Increase of money supply even if unemployment is already at a level below or near the natural rate of unemployment (NAIRU).

- Initial effect: “Much or most of the rise in income takes the form of an increase in output and employment rather than in prices”.

- The inflation phase: “The decline ex post in real wages, affects anticipations”.

- The overheating: “The rise in real wages will reverse the decline in unemployment” .. and slow GDP.

The Monetarist Business Cycle in China and other Emerging Markets between 2009 and 2013

Monetarist theories seem to be proven right in the case of China. China and other emerging markets followed the classical Friedman monetarist model:

- 2009-2010: State investments and monetary expansion helps to overcome the financial crisis. Consequently the Chinese unemployment rate was already low.

- 2010: Chinese authorities continued to expanded money supply by 30-40% per year. With the Fed’s QE2, a big part of the American increase in money supply was exported via foreign direct investments to China and other emerging markets (“Currency War”).

- 2010-2011: Friedman’s initial effect: “Much or most of the rise in income takes the form of an increase in output and employment rather than in prices.”

Income and spending increased; in China particularly investments edged up and with it the oil and gold price, the Australian dollar and the euro. The following graph shows the relationship between global M2 and the gold price.

(click to expand) source

- 2011-2012: The inflation phase: “The decline ex post in real wages, affects anticipations”. Especially in Summer 2011, global inflation drove the gold price to record highs. Bloomberg titled in April 2013 “Asia Soaring Wages Mean Rising Prices Worldwide“.

The PBoC did a lot to fight rising money supply and inflation, see below. Still the Chinese felt responsible to stop the negative effects of the euro crisis and kept money supply too long too high.

But Russian, Turkish, Indian, Brazilian and South African inflation figures are around 6% and more still today.

- 2012/2013: The overheating: “The rise in real wages will reverse the decline in unemployment” .. and slow GDP.

Chinese growth fell to 7-8% in 2012 and 2013. Brazil’s GDP increased only by 0.9% in 2012, supply issues remain. Russia is supposed to grow only by 1.8% in 2013. Cheap money and low interest rates in the US are still keeping Brazil afloat, while Argentina is already showing signs of high inflation and capital outflows. In addition, demand, especially from the austerity-driven Europe, was slowing in these often export-dependent economies.

Read on the next page about the upcoming Western monetarist cycle, when does high inflation start in developed economies?

See more for