Collateralisation reduces the credit risk on repo, which in turn can reduce the capital charge that regulators impose on lending cash. However, collateral has operational and legal risks, which means that, notwithstanding the comfort given by collateral, the primary concern in a repo should always be the creditworthiness of the counterparty. This is one of the lessons of the current market crisis.

Credit risk: the ‘double indemnity’

One of the primary benefi ts of repo is the use of collateral to reduce credit risk for the buyer, who is lending cash to the seller. However, the usefulness of repo derives not just from the use of collateral. Repo is said to offer a ‘double indemnity’ to the buyer. This means that the buyer can rely on both the counterparty and the collateral. If the seller defaults, the buyer can liquidate the collateral in order to recover its cash. On the other hand, if the issuer of the collateral defaults, the buyer can secure fresh collateral from the seller by making a margin call. Both events of default are possible, but are unlikely to occur at the same time, provided the issuer of the collateral and the counterparty are suffi ciently independent entities and their credit risks have a low correlation. Where the credit risks on the collateral issuer and the repo counterparty are relatively uncorrelated, the buyer will have materially diversifi ed its overall credit risk.

However, it is important to understand that the contributions of collateral and counterparty to the diversifi cation of credit risk are not symmetrical. If faced with a choice between a combination of good quality collateral and a poor quality seller on the one hand, versus a combination of poor quality collateral and a good quality seller on the other, buyers should not be indifferent. The former combination is generally thought unwise, whereas the latter is not.

The reason for this asymmetry is that, if the issuer of collateral defaults, the buyer can make a margin call on the seller, which is a generally straightforward process. However, if the seller defaults and the buyer decides to sell off the collateral, the buyer may experience delays and/or diffi culties. Liquidation could be delayed by the need to refer the decision to senior management and/or to serve a default notice on the seller. Depending on market conditions, collateral may be illiquid, or may be held in such quantities as to require time to sell. The buyer’s right to collateral may be challenged in the courts by the defaulting seller, in which case, the repo legal agreement would no longer be subject to the governing law of the contract: an obstructive insolvency regime may apply instead. The default could occur in the midst of a general market crisis (indeed, this could be the cause of the default itself). In this case, the buyer may fi nd that the cash generated by liquidating the collateral is less than expected, due to delays in selling or, in the worst case, the collateral is lost altogether.

It can be seen that, while collateral mitigates credit risk, it has operational and legal risks. As the collateral may turn out to be worth less than expected, it is clear that undue reliance should not be placed on collateral. Collateral should be treated like insurance, and it should be recognised that the primary credit risk in a repo is on the seller.

For this reason, it is usually acceptable to take poor quality collateral from a good quality seller, but not to try to compensate for a poor quality seller by taking good quality collateral (although this sounds sensible, collateral quality should not be allowed to drive the decision to transac

Regulatory risk capital charges

Regulatory authorities require fi nancial institutions to put capital aside in proportion to the risks they take, in order to absorb unexpected losses and continue in business without disrupting the market.

Regulators defi ne what is acceptable as capital, and prescribe a percentage, or methods of calculating a percentage, of the value of each type of risky transaction to be matched by capital of a suitable quality. The percentage takes the form of a ‘risk weight’ for each type of transaction. An overall ratio is then applied to the sum of the so-called ‘risk-weighted assets’, to give the regulatory risk capital requirement. Regulators have increasingly offered institutions the opportunity to calculate their regulatory risk capital requirements using their own risk models. The greater sophistication of internal models generally results in lower risk weights than the default percentages prescribed by regulators, or the percentages calculated using regulatory rules, for banks without their own risk models.

Capital is held by fi nancial institutions in the form of secure investments, like government bonds, and is largely funded by the issuance of equity or equity-like instruments. As the returns on government bonds are low, and equity is expensive to issue, capital has a high net cost and acts as a drag on fi rms’ profi t margins. There is, therefore, a strong incentive for regulated fi nancial institutions to channel their business into capital-effi cient transactions and to seek ways of offl oading risk from their balance sheets.

Accounting for repo

Balance sheets and other fi nancial accounts are intended to show the fi nancial condition of an institution, not the way its transactions are legally structured. This accounting objective is often stated as ‘economic substance over legal form’. The economic substance of a repo is that the risk and return on the collateral remains with the seller (the legal form is that title to the collateral passes to the buyer). Therefore, in virtually all accounting regimes, the collateral stays on the seller’s balance sheet and the only movement shown is the payment of cash. Consider the following simplifi ed balance sheets set out in accordance with international accounting standards.

| aSeller | Buyer | ||||||

| Assets | Liabilities | Assets | Liabilities | ||||

| Fixed | 90 | Current | 90 | Fixed | 200.0 | Current | 100 |

| Cash | 10.0 | Cash | 40.0 | Cash | 200.0 | Cash | 300.0 |

Investments 20.0 Retained earnings 80.0 Investments 50.0 Retained earnings 120.0 Other current 80.0 Share capital 30.0 Other current 10.0 Share capital 80.0

Assume party A sells 10 million worth of securities to party B in a repo with no initial margin. Under international accounting standards, on the Purchase Date, the securities are deducted from the investments of A and transferred to a new asset in A’s balance sheet called collateral. The Purchase Price received from B increases the cash assets of A and is balanced by a new liability on A called collateralised borrowing. On B’s balance sheet, there is no sign of the collateral securities. All that happens is that 10 million is transferred from B’s cash assets to other current assets. This is B’s claim on A. Note that A’s balance sheet expands, demonstrating that it has borrowed, but B’s balance sheet does not change in size.

| aSeller | Buyer | ||||||

| Assets | Liabilities | Assets | Liabilities | ||||

| Fixed | 90 | Current | 90 | Fixed | 200.0 | Current | 100.0 |

| Collateral | 10.0 | Collat.borrowing | 10.0 | Cash | 30.0 | ||

| 210.0 | 210.0 | 300.0 | 300.0 | ||||

Investments 10.0 Retained earnings 80.0 Investments 50.0 Retained earnings 120.0 Other current 80.0 Share capital 30.0 Other current 20.0 Share capital 80.0

On the repurchase date, A repurchases collateral from B and pays the repurchase price.

Assume this is 10.1 million.

| aSeller | Buyer | ||||||

| Assets | Liabilities | Assets | Liabilities | ||||

| Fixed | 90 | Current | 90 | Fixed | 200.0 | Current | 100.0 |

| Cash | 9.9 | Cash | 40.1 | ||||

| 199.9 | 199.9 | 300.1 | 300.1 | ||||

Investments 20.0 Retained earnings 79.9 Investments 50.0 Retained earnings 120.1 Other current 80.0 Share capital 30.0 Other current 10.0 Share capital 80.0

On A’s balance sheet, the collateral item is extinguished and 10 million of securities are returned to A’s investments. A’s cash assets are reduced by the amount of the repurchase price. On the liabilities side of its balance sheet, the net reduction in A’s assets of 10.1 million is matched by a reduction in retained earnings of 0.1 million. On B’s balance sheet, cash assets increase by 10.1 million and other current assets are reduced by 10 million (showing that B has recovered its investment of 10 million and earned a return of 0.1 million). On the liabilities side of B’s balance sheet, the return earned on the reverse repo increases retained earnings by 0.1 million. A’s balance sheet has been reduced and B’s has been increased by 0.1 million, showing A has paid a return to B for the use of the latter’s cash.

The primary risks targeted by regulators are credit risk and market risk. Regulatory capital requirements on repos for market risk arise only if interest rate positions are taken with mismatched or forward-start repos, or if currency risk is taken with cross-currency repos (where the cash and collateral are denominated in different currencies). The market risk on collateral itself is not attributed to the repo, because it will have incurred its own capital requirement for market risk, as soon as it has been purchased in the cash market. Regulatory capital requirements on repo

therefore tend to refl ect only the credit risk on the securities used as collateral.

Securities lending is viewed by regulators as comparable to repo and is included in the same capital adequacy framework.

The regulatory capital regimes in most markets are subject to international agreements between regulators aimed at preventing ‘regulatory arbitrage’ by imposing common minimum regulatory risk capital requirements on fi nancial institutions under their supervision. The fi rst international capital agreement, which came into full effect in 1988, was the Basel Accord between developed country supervisors (now known as ‘Basel I’). It applied to credit institutions and securities fi rms that were ‘internationally active’. Originally, this agreement was focused largely on credit risk, but a Market Risk Amendment was added in 1996, which also introduced the concept of fi rms calculating their regulatory risk capital requirements using their own risk models. From 2007, Basel I is being replaced by what is widely known as ‘Basel II’.

Between the introduction of Basel I and Basel II, regulators started to differentiate the business of banks and securities fi rms on the basis of the degree of credit risk in their activities. Deposits, loans, long-term holdings of securities and foreign exchange (all of which introduce sizeable, longer-term credit risk onto the balance sheet) were collected into the so-called ‘banking book’, while short-term trading securities and derivatives (which create partial or transitory credit risk) formed the ‘trading book’.

Repos of securities held in the banking book were subject to the treatment originally laid out in Basel I. A different approach was applied to repos of securities held within the trading book (although individual regulators have been allowed to insist that institutions under their jurisdiction use only the banking book approach for reverse repos). Use of the trading book approach for reverse repo also requires netting in the event of default, frequent marking to market of collateral and margin maintenance to eliminate material exposures, although these conditions do not apply if the reverse repo is ‘inter-professional’ (this exemption allowed undocumented buy/sell-backs to survive).

In the European Economic Area (EEA), the Basel Accords have been implemented through various EU Directives, which were translated into national legislation by the Member States. Basel I was implemented in the EU under the Capital Adequacy Directive (CAD) for investment fi rms and under a number of directives culminating in the Banking Consolidation Directive (BSD) for credit institutions. The EU Directive that implemented Basel II is the Capital Requirements Directive, which came into effect in 2007.

Basel I Basel II

The treatment of repo by Basel I was cursory and fairly crude. For repo, it used the risk weight on the collateral to determine capital requirements. For reverse repo, it substituted the risk weight on the repo counterparty with the risk weight on the collateral, if this was better quality. However, Basel I recognised only a limited range of collateral (cash, OECD government bonds, and bonds issued by multilateral development banks). There were also a limited number of risk weights, defi ned in terms of whether an institution was public or private, and whether or not it was headquartered in the OECD (e.g. public institutions in the OECD were assigned a risk weight of 0%, OECD banks 20% and most other institutions 100%). The overall ratio applied to the sum of risk-weighted assets (the ‘Basel Ratio’) was a minimum of 8%.

Example: A bank doing a reverse repo with an OECD-based bank (20% risk weight) holding collateral worth EUR 19 million, but owed cash of EUR 20 million, would be subject to a capital requirement of at least EUR 16,000:

(20,000,000 – 19,000,000) x 20% x 8% = 16,000

The rapid evolution of the fi nancial markets since the 1980s, and a decline in the overall amount of capital held by fi nancial institutions, led to a fundamental revision of Basel I. The product of that revision, Basel II, seeks to provide a more sophisticated regulatory regime that aligns capital requirements more closely with the risk profi le of institutions. Risk capital requirements are now only one of three so-called regulatory ‘pillars’. The others are Supervision and Disclosure.

- The Supervision pillar is a set of standards to be applied by regulators to ensure that fi nancial institutions have sound internal processes to assess the adequacy of their capital (above and beyond what is required by regulators) against a thorough assessment of their risk profi le and control environment.

- The Disclosure pillar requires institutions to publish suffi cient information to allow potential counterparties to assess their risk profi le which, it is hoped, will apply market discipline to institutions.

The regulatory risk capital requirements for market risk under Basel II are the same as those introduced under the 1996 Market Risk Amendment of Basel I. However, Basel II focuses not just on credit and market risks, but also on operational risk.

Another key innovation is that Basel II offers a menu of approaches to calculating regulatory risk capital requirements that is intended to encourage fi rms to improve their risk management systems and procedures by offering progressively better capital treatment under the more advanced approaches.

For credit risk, the approaches are:

- Simple Standardised;

- Comprehensive Standardised;

- Foundation Internal Ratings-Based (IRB); and

- Advanced Internal Ratings-Based (IRB).

The Standardised approaches

The Simple Standardised approach is basically the same as Basel I.

The Comprehensive Standardised approach replaces the risk weights used in Basel I with credit ratings from, among others, recognised rating agencies. This has led to a major re-rating of counterparties and collateral.

Example: Under Basel I, Turkey had a risk weight of 20%, since it was a member of the OECD, but Singapore was 100%, since it was not. Under the Comprehensive Standardised approach to Basel II, Turkey, which is rated BB-, has a 100% risk weight, while Singapore, rated AAA, is 20%.

The Comprehensive Standardised approach also uses the concept of haircuts to adjust the values of both exposures and collateral to take account of the volatility of prices. A set of haircuts is prescribed by Basel II, but more sophisticated institutions are allowed to calculate their own estimates of price volatility or use Value at Risk (VaR) models.

The Standardised approaches place various fl oors under the capital charges for repo, but offer numerous exemptions or ‘carve-outs’. For example, where the counterparty is a ‘core market participant’, the collateral is 0%-weighted, and the repo is correctly documented and margined daily, the capital charge can be reduced to 0%.

Internal Ratings-Based approaches

The IRB approaches allow institutions to calculate the components of the risk weights.

Under the Foundation IRB approach, own calculations can be used to estimate the component called the ‘Probability of Default’.

The Advanced IRB approach also allows the own calculation of components called the ‘Loss Given Default’ (this number is the one reduced by collateral) and ‘Exposure at Default’, which is the number by which the risk weight is multiplied to give the value of the risk-weighted asset (the capital charge is then 8% or more of this number).

To adopt more sophisticated approaches, institutions must meet increasingly tougher operational conditions. For repo, these conditions include legal certainty about the title to collateral and the right to net, low correlation between the credit risks on collateral and the counterparty, robust collateral management and the secure management of collateral. The rewards are the ability to use a broader range of assets as collateral and lower capital charges.

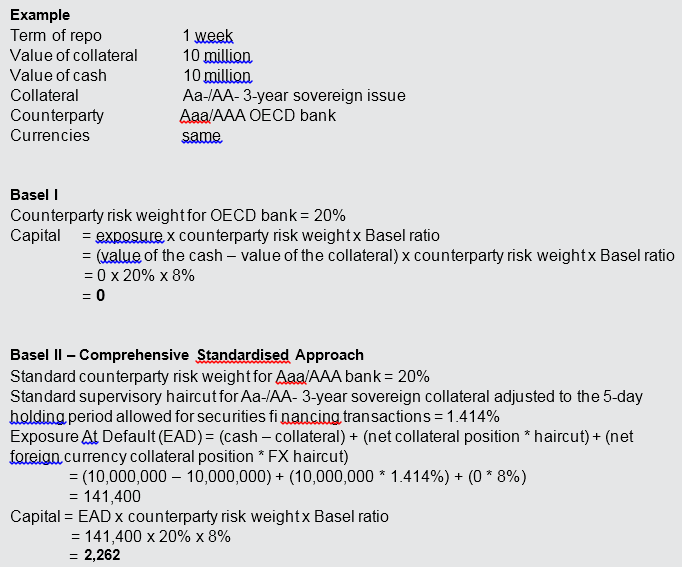

The following examples compare the regulatory risk capital calculations under Basel I and the various approaches of Basel II.

Repo Documentation

The performance of repo depends on the buyer’s right to collateral. In order to minimise legal risks, it is prudent to have a written contract in the form of a master agreement. The standard for cross-border repo markets in Europe and elsewhere is the Global Master Repurchase Agreement (GMRA). Such documentation is also important for reinforcing a party’s netting rights in the event of default by a counterparty, and in setting out operational procedures such as margining and manufactured payments. The basic GMRA has been adapted to specialist uses and certain domestic markets through the use of annexes.

In an undocumented buy/sell-back, the rights and obligations of the parties in the event of a default by one of the parties are less clear than in a repurchase agreement or documented buy/sell-back. This is especially true of the right of the non-defaulting party to net obligations with a defaulting counterparty.

Global Master Repo Agreement

In the early days of the European repo market, counterparties drew up their own contracts, but disagreements prompted efforts to produce standard agreements,

both for domestic and international repo transactions. The lead in the international market was taken by what is now the International Capital Markets Association (ICMA), through the committee that became the European Repo Council (ERC). In 1992, the ICMA published the fi rst version of the GMRA. This was done in conjunction with the ICMA’s US counterpart, the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association (SIFMA – formerly called the PSA and then TBMA), whose domestic Master Repurchase Agreement formed the basis of the fi rst GMRA. Copies of the GMRA are available on the ICMA website (www.icmagroup.org).

In 1995 and 2000, the GMRA was updated to take account of market developments and incorporate improvements suggested by experience. Thus, the GMRA 1995 (the version updated in 1995) incorporated lessons learnt in the Barings crisis of 1995, in particular, the need for more time to liquidate collateral located in other time zones. The GMRA 2000 (the version updated in 2000) refl ected the experience of the Long-Term Capital Management (LTCM), Russian and Asian crises of 1997-98, and the additional time needed to liquidate illiquid collateral during a crisis.

The function of legal agreements is two-fold:

- To facilitate trading by having counterparties agree as many general terms and conditions as possible, in advance of executing individual transactions. This saves time and helps to avoid misunderstandings at the point of trade.

- To set out clearly the rights and obligations of the counterparties during the life of the transaction (e.g. in respect of margin maintenance) and in the event of a problem arising (e.g. failure to deliver collateral or a default by one of the parties). By setting out clearly the intention of the counterparties, it is hoped that courts will uphold the contract in disputes between the counterparties or challenges from third parties.

The specifi c issues that a repo legal agreement is expected to address include the following:

- The transfer to the buyer of absolute legal title to collateral, margins and substitute collateral.

- Procedures for marking collateral to market, including price sources.

- Procedures for margin maintenance to eliminate material differences between the values of cash and collateral.

- The defi nition of ‘events of default’, and the consequent rights and obligations of the counterparties.

- The obligation to fully close out and set off (net) opposing claims between counterparties in the event of default.

- The management of coupon and other payments on collateral (i.e. manufactured payments).

- The rights and obligations of the counterparties if collateral fails to be delivered.

- Procedures to be followed if rights of substitution of collateral are exercised.

Annexes

The GMRA was designed for repurchase agreements between institutions dealing

for their own account (i.e. principals) using fi xed-income collateral paying coupons gross of withholding tax. In order to be able to use the agreement to document buy/ sell-backs, repos involving an agent (e.g. a fund manager dealing on behalf of a client), or repos involving other securities, it is necessary to modify the standard agreement by attaching annexes. Annexes have been published by the ICMA to adapt the GMRA to:

- buy/sell-backs;

- repos between an agent and a principal;

- repos of equity;

- repos of money market securities; and

- repos of net-paying securities.

In addition, because the GMRA is governed by English law, it has been necessary to adapt it for use in other jurisdictions (e.g. Australia, Canada and Italy). Annexes have also been published for:

- the UK-gilts market by the Bank of England;

- the Australian market by the Australian Financial Markets Association (AFMA); and

- Japanese securities by the Japanese Securities Dealers Association.

Legal opinions What happens if a counterparty defaults

In addition to publishing and periodically updating the GMRA, the ICMA commissions legal opinions on the enforceability of the GMRA as a whole or, in some cases, just on the enforceability of the netting provisions in different jurisdictions. These are vital in minimising legal risk and giving confi dence to the market and its regulators about the certainty of contracts and the consequences of a default. By 2007, there were legal opinions for over 50 countries. Work is also being undertaken to extend opinions to more countries and, where opinions already exist, to cover insurance companies, hedge funds and mutual funds. The ICMA updates its suite of legal opinions annually.

One of the main legal risks which legal opinions seek to address is so-called ‘re-characterisation risk’. This is the possibility that a court may refuse to accept that legal title to collateral has been transferred to the buyer in a repo contract. The risk is often greater for collateral transferred as margin or as a substitute. If a repo is re-characterised, it is possible that it could be re-characterised as a pledge, or even as an unsecured loan.

A key chapter of the GMRA deals with default by one of the counterparties. A standard set of events of default is listed in the GMRA. These include acts of insolvency and failure to make cash payments. Failure to deliver collateral is not a standard event of default but, under the GMRA 2000, the counterparties can agree to make it one. In contrast to the ISDA Master Agreements, there are no credit triggers or cross-default clauses (these legal provisions put a counterparty into default if they suffer a credit ratings downgrade or are in default on another master agreement): this is to avoid undermining an institution in diffi culty by automatically stopping their funding because of problems in a possibly unrelated market. Counterparties can also add their own events of default to the standard list, but this may create legal complications.

If an event of default occurs, and it is one of two particular acts of insolvency, the party which has committed the act is automatically in default. If any other event of default occurs, a default notice has to be served on the party which has committed the act. Except if the event of default is a ‘failure to perform other obligations’ (in which case, there is a 30-day ‘cure period’), a notice places the counterparty on which it is served in immediate default.

In practice, serving default notices has sometimes proven diffi cult. Consequently, the GMRA 2000 requires only two reasonable attempts to be made to serve a default notice, after which the non-defaulting entity can certify that an event of default has occurred.

As soon as a counterparty is formally in default and any cure period has expired, the non-defaulting party can close out and set off all the repos it has outstanding with the defaulter that are documented under the same legal agreement. This means that all outstanding repo contracts are terminated (closed out) and their repurchase date accelerated for settlement as soon as possible. The resulting present values of obligations owed by the defaulter are netted (set off) against the present values of obligations owed to the defaulter, leaving a residual net obligation in one currency. Netting may leave the non-defaulter with a small exposure to the defaulter, or none at all.

If a seller defaults, the risk to the buyer is that, between the last margin payment or transfer, and the post-default liquidation of collateral, the value of that collateral has fallen to less than the sum of the purchase price plus the accrued return on the cash loaned. If a buyer defaults, the risk to the seller is that, between margining and the post-default repurchase of his lost collateral in the cash market, the value of that collateral has risen to more than the sum of the purchase price plus the accrued return on the cash borrowed.

Non-defaulters can add reasonable expenses to the obligations of the defaulter, but cannot seek ‘consequential damages’, in other words, all the downstream losses incurred as a result of the default. However, the GMRA 2000 does allow for recovery of the costs of replacement, re-hedging or unwinding hedges.

Agreements such as the GMRA are so-called ‘master agreements’, which means that all repos between the signatories of such agreements fall under the terms of the agreement unless specifi cally excluded. The consequence is that individual transactions are incorporated into a single contract. This helps to ensure the effectiveness of netting in the event of default by one of the parties.

A key requirement of close out and set off is, of course, the valuation of collateral. The GMRA 2000 offers considerable fl exibility to the non-defaulter in the form of a menu of alternative methods, particularly designed to accommodate illiquid collateral. Thus, the non-defaulter has the choice of:

- market quotes;

- the prices actually realised on the sale of collateral or other holdings of the collateral asset; or

- its own judgement of ‘fair value’ in cases where quotes are not deemed to be ‘commercially reasonable’.

In order to allow time to get market quotes or dealing prices, the deadline for valuation is fi ve business days after default. However, fair value can be fi xed even after this deadline in exceptional circumstances.

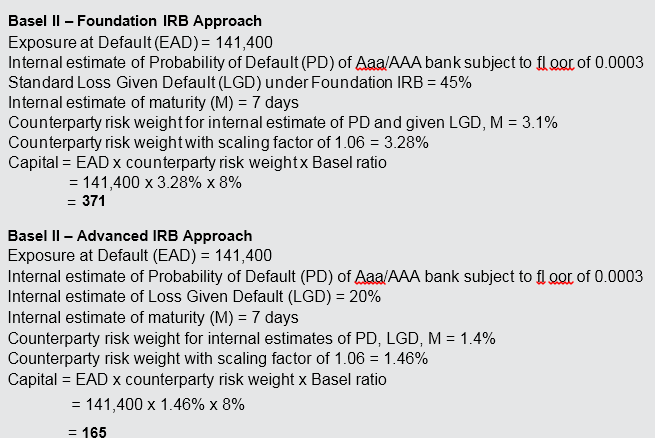

The European repo marketThe origins of the European repo market are obscure. Repo and repo-like instruments can be traced back to the 19th century in the United Kingdom and France; a buy/ sell-back market, with a large retail segment, was operating in Italy by the 1970’s; and US investment banks imported the repurchase agreement into Europe during the 1980’s to make up for the lack of securities lending markets in countries such as Italy and to support trading in bund futures from 1988. However, take-off for the European market came with the reform of the French market in 1994 and the opening of a sterling repo market in the United Kingdom in 1996. Since that time, the European repo market has grown at a dramatic pace, interrupted occasionally by market crises, including the current ‘credit crunch’. Key drivers have included regulatory capital pressure on unsecured lending, which has led to its progressive substitution by repo, and the rapid growth of hedge funds and proprietary trading in fi xed income. The credit crunch is likely to accelerate the substitution of unsecured lending by repo. The sample of the European repo market surveyed by the ICMA every six months since 2001 peaked at EUR 6,775 billion in June 2007 (in terms of outstanding contracts). Given that the ICMA survey has been based on a sample of some 60-80 fi rms, albeit including the largest repo traders, the full size of the European market is obviously somewhat larger than the survey number: it is also larger than the US market. |

ICMA survey headline numbers 2000-2008 |

| Following the collapse of Lehman Brothers in September 2008, fi nancial markets contracted sharply, as banks accelerated the de-leveraging of their balance sheets. The December 2008 ICMA survey showed a 26% contraction from June 2008.

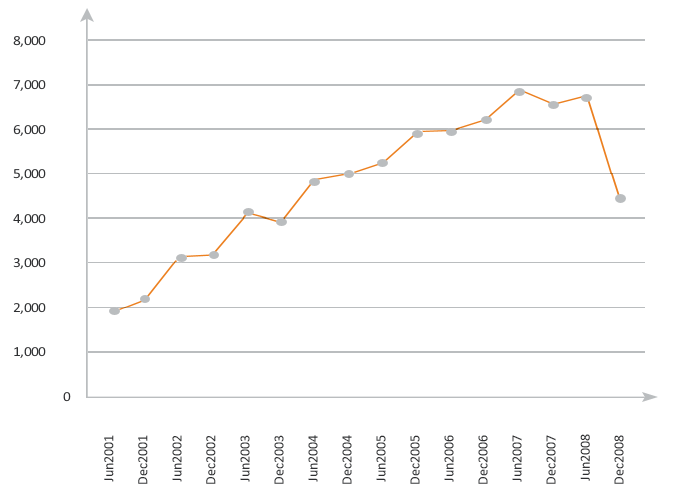

Most trading in the European market is conducted bilaterally between dealers, using the telephone or bilateral text-messaging systems. A declining proportion has been arranged by voice-brokers, and an increasing proportion by electronic trading systems such as BrokerTec, Eurex Repo and MTS. |

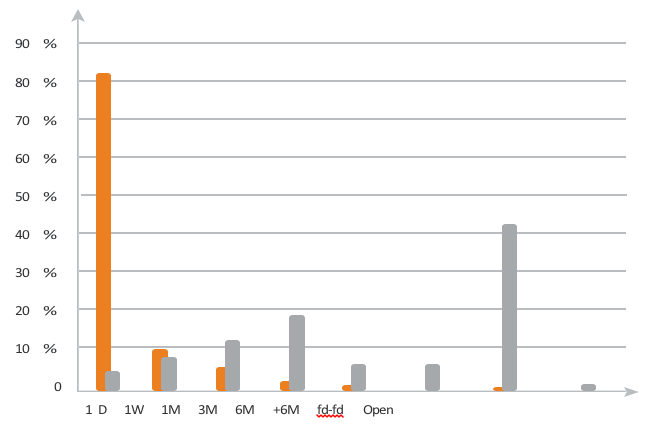

Counterparty analysis of ICMA surveys over 2001-2008 |

| Electronic trading was introduced by MTS in 1990’s, fi rst into the Italian market and then other European markets. The original electronic trading systems displayed the identity of counterparties; some still do. Anonymous trading was introduced in 2000, when BrokerTec was linked to LCH.Clearnet Ltd’s central clearing product, RepoClear.

The function of a CCP is to step into each trade, to become the buyer to every seller and the seller to every buyer. It is therefore unnecessary for the original counterparties to ever know each other’s identity, which allows anonymous trading. This is important to dealers, as it hides their trading from other fi rms and reduces the market impact of their transactions. The other benefi t of a CCP is the automatic multilateral netting of trades. Example: If A repos a bond to B and B repos the same bond to C using a trading system with a CCP, the CCP will step into the middle of the two trades, allowing B’s trades to be set off and cancelled, and reducing its exposure to credit risk. Without the CCP, B’s trades could not be set off and it would have to carry more risk. According to the ICMA survey, electronic repo trading reached a peak of over 28% of outstanding contracts in December 2008. Anonymous electronic trading simultaneously reached almost 18%, boosted by the attraction of netting and risk reduction in the current crisis. The ICMA fi gure does not include B2C electronic trading between dealers and customers across systems like TradeWeb or the proprietary sales systems used by a number of dealers. A major innovation in the electronic trading of repo has been the concept of ‘GC fi nancing’, originally introduced by the DTCC in the US market. In contrast to the other electronic systems, that trade specifi c bonds, GC fi nancing systems use triparty agents or collateral management systems to automatically select eligible bonds from the seller’s account. Eligible bonds are those included in an agreed list, or basket, of acceptable collateral. Electronic trading tends to be very short-term. Indeed, most electronic trades have a term of one day. In contrast, transactions arranged by voice-brokers tend to be longer-term or forward-forward, as these types of repo are more complex and risky, and require negotiation. |

Maturity distributions of electronic and voice-broker repo in ICMA December 2008 survey |

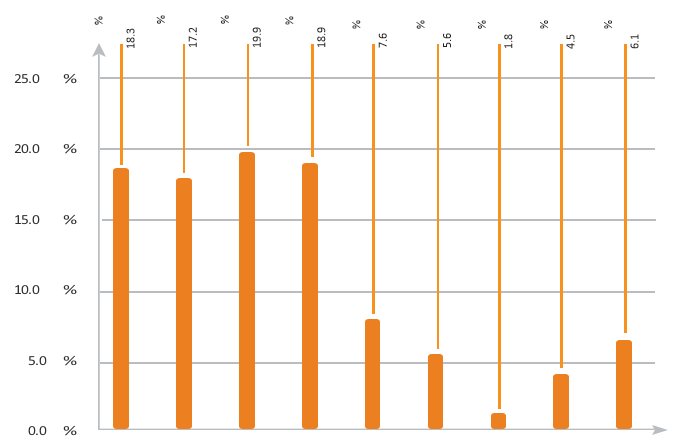

| Figure 19 shows the maturity distribution of European repo market, as seen through the ICMA survey. About two-thirds of transactions have a remaining maturity of one month or less. However, that leaves reasonable volumes of business out to one year and beyond. There is also a signifi cant amount of open repo, although this declined in 2008 as a result of the credit crisis (open repos cannot be netted, whereas fi rms have been keen to maximise netting in order to reduce their risk exposures).

The maturity of repo business has a seasonal pattern, with fi rms seeking to lock in longer-term fi nancing over the year-end holidays. |

Maturity distribution of ICMA December 2008 survey |

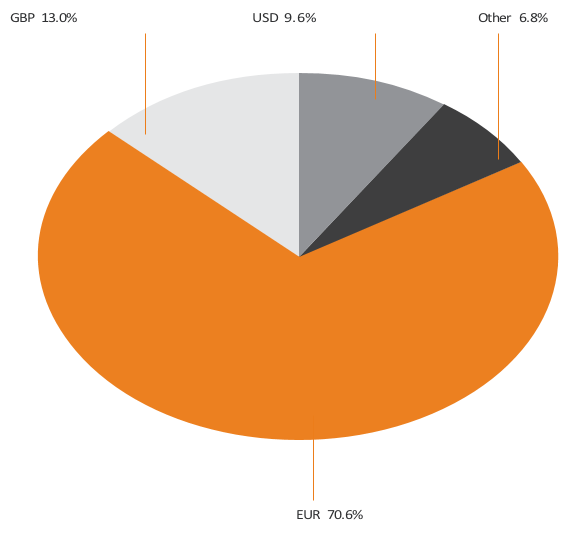

| As one would expect in the European repo market, the most important currency is EUR. Important roles are played by GBP and USD. Electronic trading is concentrated in EUR, with smaller contributions from GBP and the CHF. |

Currency distribution of ICMA December 2008 survey |

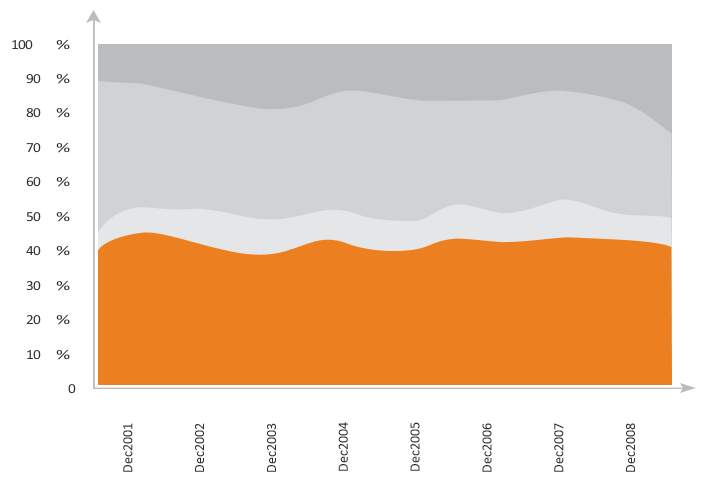

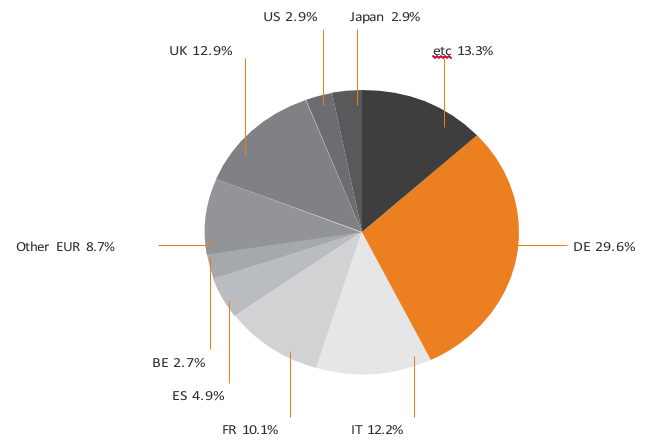

| The large bulk of collateral traded in the European market is government bonds.

However, the importance of non-government or credit repos is understated by the ICMA survey; much of this collateral is traded in the triparty sector of the repo market and the share of government bonds has tended to decline over time – although it bounced back in the fl ight to quality which followed the collapse of Lehman in 2008. The principal source of collateral is Germany, followed by the United Kingdom, Italy and France. The use of collateral is still hampered by the fragmentation of settlement systems in Europe, for which reason, repo markets, such as Spain, are still largely domestically orientated. Most repo contracts traded in Europe are fi xed-term, but there is an important fl oating-rate repo sector (over 10%). Most fl oating-rate repo is conducted in the French market, but the product has become more popular in other European markets. Copies of the ICMA’s semi-annual European repo market surveys can be downloaded from www.icmagroup.org. |

Collateral distribution of ICMA December 2008 survey |

Annex 1 – Glossary

Buyer

The party to a repo that purchases collateral on the purchase date and commits to sell back equivalent collateral on the repurchase date or on demand, in the case of open repo. The lender of cash.

Buy/sell-back

A type of repo (cf. repurchase agreement) that traditionally has not been documented under a master agreement, in consequence of which, each leg of this type of repo forms a separate contract. However, since 1995, it has been possible to document buy/sell-backs. Whether documented or not, the counterparties to a buy/sell-back do not undertake margin maintenance. Instead, in documented buy/ sell-backs, material differences between the value of the cash and collateral can be eliminated by the early termination of the transaction, and the simultaneous creation of a new contract for the remaining term to maturity, in which the purchase price is realigned with the value of the collateral or vice versa (all other terms of the transaction remaining the same). If coupons or dividends are paid on the collateral during the term of a buy/sell-back, the buyer re-invests an equal amount of money until the repurchase date, when the re-invested sum is paid to the seller by deduction from the repurchase price due to be paid to the buyer.

Collateral

The assets sold in a repo. Legal and benefi cial title to the collateral should be transferred from the seller to the buyer for the term of the transaction. Typically, collateral takes the form of fi xed-income securities, usually government fi xedincome securities. In the event of a default by the seller, the buyer should have the right to liquidate the collateral in order to recover some or all of the cash owed by the seller.

Corporate value date

In a repo, the purchase price and the collateral are usually exchanged on a money market value date, rather than on a capital market settlement date. However, where one of the parties cannot manage this earlier settlement, the value date of the repo may be deferred until the conventional capital market settlement date, which is referred to as a ‘corporate value date’.

Delivery repo

A repo in which the custody of the collateral moves from the seller to the buyer for the term of the transaction (cf. hold-in-custody repo and triparty repo).

Equivalent

At the maturity of a repo, the buyer is obliged to return ‘equivalent’ collateral to the seller. Where the collateral is fi xed-income securities, ‘equivalent’ means the same issue of securities. However, it is necessary to use the term ‘equivalent’ because, during the term of transaction, the buyer can sell the collateral to a third party, and will then have to buy back the collateral from a fourth party, in order to settle with the seller on the repurchase date. In terms of property law, the collateral returned by the buyer will not be the same as the collateral sold to the buyer at the start of the transaction (although there will be no difference economically). The use of the term ‘equivalent’ also allows the legal defi nition of repo to accommodate collateral in the form of equity, which can be transformed during the term of a repo by corporate events such as take-overs, rights issues, etc.

ERC

The European Repo Council (ERC) is a regional sub-committee of the International Repo Council established by the International Capital Market Association (ICMA) to represent member fi rms active in the repo market in Europe. Among other things, the ERC organises a semi-annual survey of the European repo market. Details of the survey and the other activities of the ERC can be found on the ICMA website, www.icmagroup.org.

Floating-rate repo

A repurchase agreement in which the repo rate is linked to an index such as EONIA and is accordingly periodically re-fi xed (in the case of EONIA, it would be re-fi xed daily). The rate may incorporate a spread under or over the index (e.g. EONIA minus 3 basis points).

Forward-start repo

A repo that starts on a forward date and ends on a later forward date.

Forward price

The traditional method of quoting buy/sell-backs (cf. repo rate). The forward rate is the forward break-even price, quoted clean of accrued interest, of the collateral on the repurchase date. It is equal to the repurchase price of the collateral minus the accrued interest that will be outstanding on the collateral on the repurchase date, quoted as a percentage of the nominal value of the collateral.

General collateral (GC)

Where the seller in a repo has some choice about precisely what piece of collateral to deliver to the buyer. For example, the buyer may be willing to accept any of a number of certain government bond issues: the precise issue is decided by the seller. GC repos are driven by the need to borrow and/or lend cash, rather than the identity of the collateral (cf. specials), and constitute a money market transaction. GC repo rates are highly correlated with other money market rates.

Hold-in-custody (HIC) repo

A repo in which the seller retains custody of the collateral, even though legal and benefi cial title passes to the buyer. Used where there are practical diffi culties or heavy costs in moving collateral. HIC repo exposes buyers to the risk of ‘doubledipping’ by the seller (i.e. the seller using the same piece of collateral for more than one repo).

Initial margin or haircut

The excess of the value of collateral over the purchase price on the purchase date of a repo. Initial margin is usually intended to protect the buyer against the illiquidity of collateral and the credit risk on the seller. Very occasionally, initial margins are used to protect the seller against credit risk on the buyer, in which case, they measure the excess of the purchase price over the value of collateral. Initial margins are usually expressed as the percentage ratio of the value of the collateral to the purchase price (e.g. 102%).

Manufactured payment

A payment from the buyer to seller, triggered by the payment of a coupon or dividend on collateral during the term of a repurchase agreement. The coupon or dividend will be paid by the issuer of the collateral to the buyer, given that the buyer has the legal and benefi cial title to the collateral during the term of the transaction. However, the seller, who retains the risk on the collateral, will expect compensation for that risk. This is paid by the buyer in an amount equal to the coupon or dividend. Manufactured payments should be made on the same day as the coupon or dividend payment.

Margin maintenance

Where material differences arise in a repurchase agreement between the value of cash owed by the seller and the collateral held by the buyer, giving rise to an unintended credit exposure to one of the parties, they can be eliminated by the payment of cash or, more usually, the transfer of collateral, from the party that is over-collateralised to the one that is under-collateralised. Margin calls are initiated by the under-collateralised party. The calculation of margin calls requires the marking-to-market of the collateral.

Open repo

A repurchase agreement with no fi xed repurchase date, that runs until one of the two parties terminates the transaction by giving due notice to the other. Interest is usually calculated daily but rolled over and paid monthly or, if the transaction is terminated before the month-end, on the repurchase date.

Purchase date

The value date of a repo (i.e. when the purchase price and collateral are exchanged by the buyer and seller).

Purchase price

The amount of cash paid by the buyer to the seller on the purchase date in exchange for collateral. The purchase price is net of any initial margin or haircut.

Repo

Generic term for a sale of collateral and a simultaneous agreement to repurchase equivalent assets on a future date, or on demand (open repo), for the same value plus the payment of a return on the use of the purchase price during the term of the transaction.

Repurchase agreement

Also known as a classic repo, US-style repo, or all-in repo. A type of repo (cf. buy/ sell-back) that is typically documented under a master agreement, in consequence of which, both legs of the transaction form a single contract. In a repurchase agreement, the counterparties undertake margin maintenance, and the repo may be subject to an initial margin or haircut. In addition, the buyer can grant rights of substitution to the seller, and the payment of coupons or dividends on the collateral during the term of the transaction triggers an immediate manufactured payment to the seller.

Repo rate

The percentage per annum rate of return paid by the seller for the use of the purchase price over the term of a repurchase agreement and included in the repurchase price.

Repurchase date

The maturity date of a repo.

Repurchase price

The amount of cash paid by the seller to the buyer on the repurchase date in exchange for equivalent collateral. The repurchase price includes the return on the cash and, in the case of buy/sell-backs, is net of any reinvested coupon or dividend paid on the collateral during the term of the repo.

Reverse repo

The buyer’s side of a repo. The buyer is said to ‘reverse in’ collateral (whereas the seller is said to ‘repo out’ collateral).

Right of substitution

The right that may be given by the buyer to the seller, during the negotiation of a repurchase agreement, for the seller to recall equivalent collateral during the term of the transaction, and substitute collateral of equal quality and value. The substitute collateral must be considered reasonably acceptable to the buyer.

Seller

The party to a repo that sells the collateral for cash on the purchase date and commits to buy back equivalent collateral on the repurchase date, or on demand in the case of open repo. The borrower of cash.

Special collateral

Collateral on which the repo rate is materially below the GC repo rate for the same term. This differential is caused by the demand for this collateral, which is manifest in offers of cheap cash from potential buyers.

Triparty repo

A type of repo (either repurchase agreements or buy/sell-backs) in which a third-party agent (usually the common securities custodian for the two parties) undertakes the settlement and management of the transaction, including the initial and fi nal exchange of cash and collateral, the imposition of initial margins, margin maintenance, substitution of collateral and manufactured payments. Legal and benefi cial title to the collateral is transferred from seller to buyer, but custody is transferred between sub-accounts held by the triparty agent, which reduces the cost of settlement and operational risk, facilitating the use of baskets or unusual types of collateral.

See more for