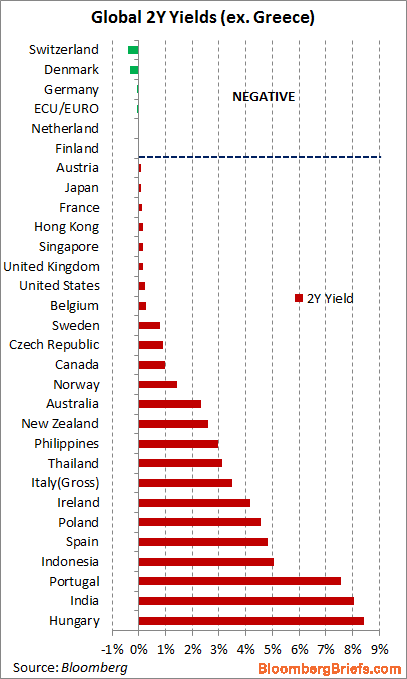

We judge that negative or close to zero yielding government bonds reflect four points: Risk off environment, long-run currency gains on currency with low inflation, insufficient supply of government bonds for bank refinancing purposes.

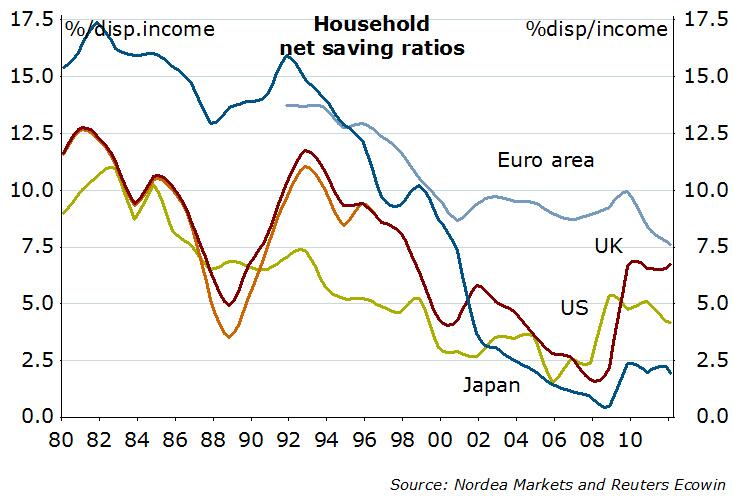

1) Risk-off:  Before the 2008 crisis, people increased their debt and reduced their savings rate, the ratio between new savings and their income.

Before the 2008 crisis, people increased their debt and reduced their savings rate, the ratio between new savings and their income.

Now this has become different, everybody seeks a safe-haven to preserve wealth. Given the demographical issues, household savings rates have stabilized and do not fall any more.

Swiss investors hate risk even more than others. Therefore they do not dare to “export” their trade and current account surplus of 14% of GDP with an equivalent flow inside the “financial account” of the balance of payments. They refuse to purchase foreign bonds, stocks or direct investments and prefer to create a Swiss real estate bubble, with the associated lending.

This applies in particular to risk-averse pension funds that buy such near zero-yielding bonds denominated in CHF.

2) Currency Gains in the long-run: Similar to the Czech Krona, and the Chinese Yuan, currencies with strong current account surpluses and low inflation must appreciate over time. Hence despite low yields, investors will obtain a currency gain one day – early in the case of the yuan, a bit later with CZK bonds and finally also on CHF bonds. Global deflation has moved the currency gain on CHF into a more remote future. The Czech and the Swiss central banks execute a new form of monetary policy. It is called QEE , quantitative easing and exchange rate intervention. The fact that these currencies, CNY, CZK and CHF must appreciate thanks to lower inflation and competitiveness is reflected in the interest rate parity. Holding these bonds, risk-averse investors sleep well.

The Russian Rouble currently represents the opposite: Inflation is too high and the central bank cannot slow it down. This has been intensified by the oil price collapse.

Negative yields can arise when point 1) is more important than 2).

3) Banks need government bonds to refinance themselves. Those safe assets function indirectly as means of refinancing for rising money supply and is needed to give loans to the private sector. When government debt is low, then the bond supply is insufficient compared to the desire to invest. Typically central banks would hike rates to limit investments. They currently do not hike rates, because money supply does not translate in higher wages. See the strongly rising Czech money supply and the massive growth of Swiss money supply.

Bank risk management requires a certain maturity equivalence between collateral and credit to the private sector. Therefore the bank is able to pay negative yields on certain maturities. But the bank still profits on the package between negative bond yields and gain on the loan.

The Czech case is mostly driven by points 2) and 3) while the Swiss one corresponds mostly to 1) and 2).

Furthermore, low inflation globally contributes to low bond yields: Easy money led to heavy investments in China and other Emerging Markets. Easy money helped to distribute labor globally, often into less utilized resources in previously less privileged countries.

Finally over-capacity and over-producing of goods in these countries helped to reduce prices around the world.

Near-Zero Bond Yields in 2014

The Swiss 50 year bond maturing on 2064 now trading at a yield to maturity of less than 0.9%.

Point 2 and 3 become clearer when we look at the article provided by the Financial Times

Someone clearly thinks this Czech is not going to bounce.

The Czech Republic’s 10-year bond yield has fallen below Germany’s for the first time since 2007 this week, and dipped to the lowest since at least March 2007 as investors have rushed to snap up the country’s sovereign bonds.

Even for a country known as central and eastern Europe’s safe haven, this is a pretty eye-catching move.

It is largely driven by the central bank’s currency floor at CK27, extremely low inflation and rock-bottom interest rates, coupled by the ample liquidity of the local banking sector and a shortage of government bond supply.

There is also a rumour that the Czech Republic will be moved to JPMorgan’s emerging market bond index, which would bolster inflows, even though the country is one of the most developed in the region.

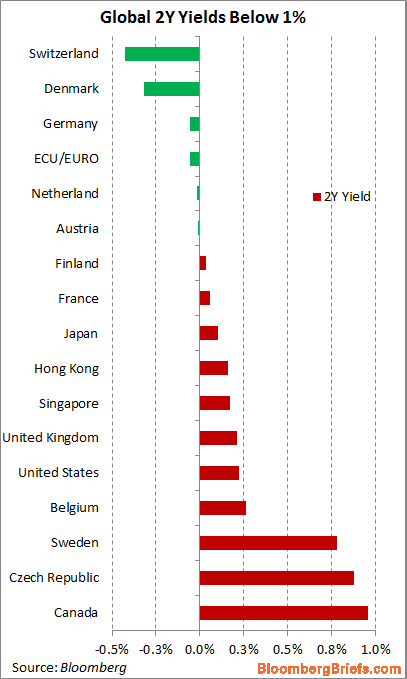

2 Years Government Bonds Yields under zero in 2012 and 2013

After the first time End May 2013, the 2 year German Schatz turns negative again on July 18th 2013.

|

German June 2014 Schatz Average Yield -0.06% vs 0.10% on June 20, 2012

|

Swiss 2yrs still at -0.4%

Government Bonds on Financial Times, on Forexpros

On Bloomberg more Yields:

French BTAN 1 year, BTAN 2 years, BTAN 5 years, French 10 years

Italy 10 years

Spain 10 years

German Bund 10 years German Bobl 5 years (“Bundesobligationen”),

German 2 years Schatz (“Schatzanweisungen”)

The spread between Swiss 10 yrs Eidgenossen and German Bund

US Treasuries: 10 years, 5 years US Treasuries

Bloomberg Bonds

Internet Quickstart 1M 3M 1Y 2Y 5Y 10Y 15-30Y Yield curve Inflation

Switzerland

(Eidgenossen) yield yield yield yield

yield yield yield Swiss inflation

Germany

(BuBills, Schatz,

BOBL, Bund)

yield yield yield yield

futures yield

futures yield

futures yield

Germany German CPI

France

(BTAN,Oat) yield yield yield yield

yield

yield

yield France CPI

Italy

(BTP) yield yield yield

yield

yield

yield Italy CPI

Spain

(Bonos) yield yield yield

yield

yield

yield Spain CPI

UK (Gilts) yield yield yield yield

futures yield

futures yield

futures yield

UK UK CPI

United States

(Treasuries) yield yield yield yield

futures yield

futures yield

futures yield

US U.S. CPI

Japan

(JGBs) yield yield yield yield

futures yield yield

futures yield Japan Japan CPI

Internet Quickstart

(Eidgenossen)

(BuBills, Schatz,

BOBL, Bund)

futures

futures

futures

(BTAN,Oat)

(BTP)

(Bonos)

futures

futures

futures

(Treasuries)

futures

futures

futures

(JGBs)

futures

futures

See more for