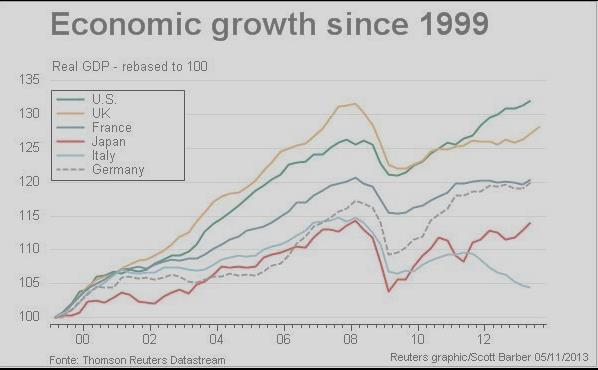

Mainstream economists speak of two Japanese lost decades(s) between 1990 and 2009. Often the United States and the UK are seen as leaders in growth. Some statistics might confirm this:

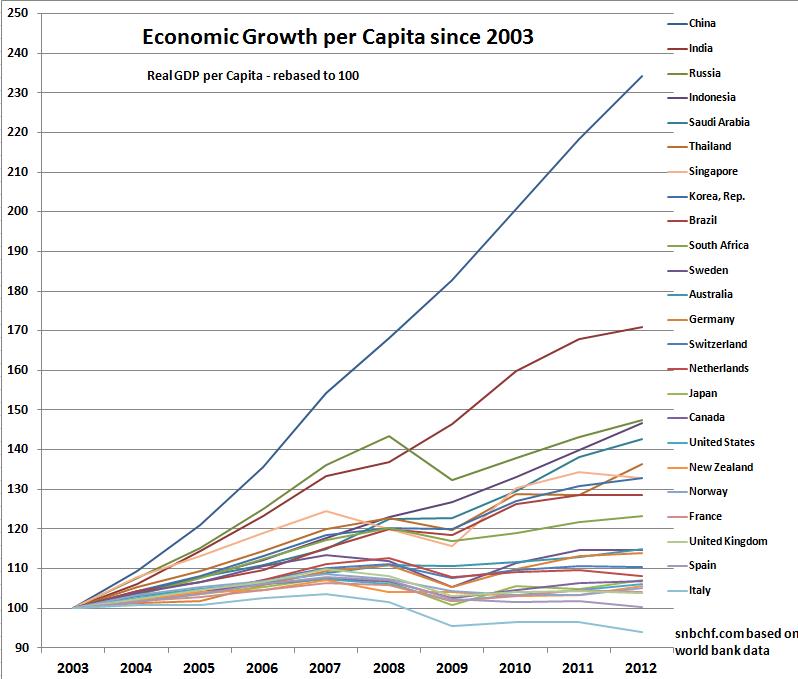

When we look at more subtle criteriom, namely GDP growth per capita, available at the world bank, we see a different picture. China and then nothing, nothing, then India, Russia, Indonesia, Saudi-Arabia, Thailand and somewhere at the bottom our well known “developed” nations.

When we look at more subtle criteriom, namely GDP growth per capita, available at the world bank, we see a different picture. China and then nothing, nothing, then India, Russia, Indonesia, Saudi-Arabia, Thailand and somewhere at the bottom our well known “developed” nations.

The developed countries with the strongest growth have ties to China: Australia exports commodities to China and profited on the price increase. Germany, Finland and Sweden export capital goods and engineering products. The Netherlands is one of the leaders on global trade, while the Swiss have a huge positive global investment position and have built factories around the world.

The U.S. provided the basis for the Chinese ascent: Americans spent and spent until 2008. The U.S. trade deficit financed the huge investments in China that are still keeping Chinese firms competitive despite rising salaries (more on this).

GDP per Capita (data source world bank), click on graph to expand

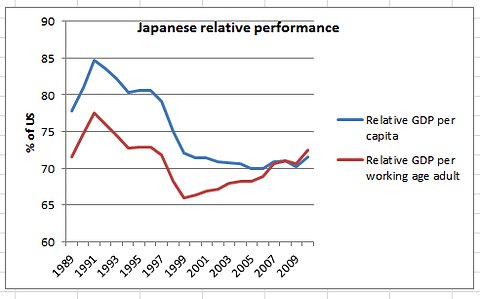

As also recognized by Paul Krugman, Japan has seen a stronger growth per capita in working age than the U.S. or the UK. Seemingly the GDP growth in the two latter countries was mainly driven by population growth and immigration assisted by the global lingua franc English.

GDP Growth per Capita in Developed Nations in the following order: Australia Sweden Germany Switzerland Netherlands Japan Canada United States France United Kingdom Ireland Spain Italy Greece - Click to enlarge

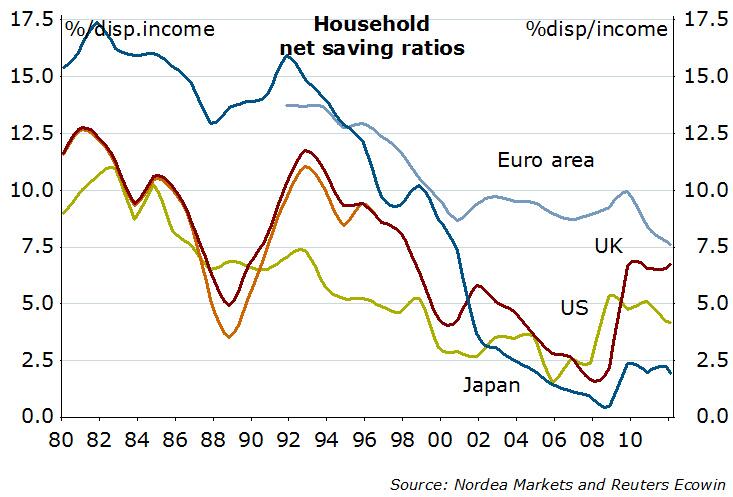

Larry Summer’s recent idea was that U.S. consumer spending is paramount, otherwise the U.S. will sink in a secular stagnation.

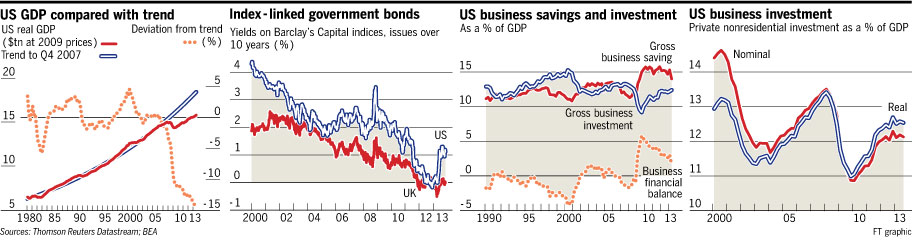

Currently the U.S. economy is improving precisely because investments are finally increasing… but due to continuing fear of debt, on both lenders and borrowers side, investments are driven more by (previously existing company) savings than before the financial crisis.

source Financial Times

We think that Summers’ concentration on spending will be counterproductive, given that the household savings rates are too low.

Most interestingly, the Japanese savings rate was constantly falling during the two “lost decades”. Growth was created by exports. public spending and investments and because prices fell more quickly than incomes.

For us, the biggest Japanese issues were falling incomes after the huge bubble in the late 1980s. Weaker incomes, however, were unavoidable because of exports: Japan had to compete with cheap China and South Korea.

Recently the picture changed and Japan has trade deficits: The deficits was mostly caused by the fact that all nuclear plants have been shut down currently but there were some other reasons.

German or Fins concentrated on capital goods, they were better in innovation. They expanded their trade surplus, but Japanese did not diversify their exports away (enough) from possible “Chinese copies”.

As visible above, during the “lost decades” Japanese decreased their savings rate. Salaries did not rise, the savings rate remained low. Firms accumulated (trade) surpluses and paid down the debt obtained during the Japanese bubble, because falling collateral aka house prices sustained this need.

Weak population growth seems to be a common issue in all these countries. But still Chinese salaries are low; we are more than one decade away from the moment when China becomes Japan and – as Summers said – possibly the Americans become Japanese first.

Read also:

What drives the economy? Consumer spending or saving/investment?