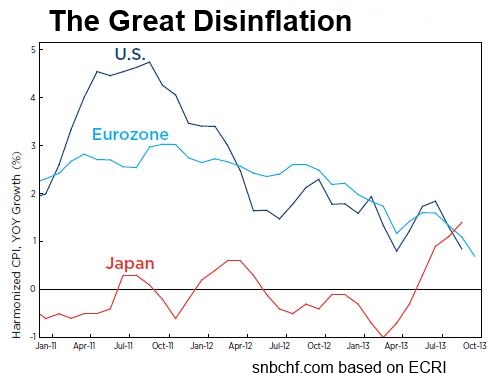

Recently, investors moved out of bonds with the expectation that inflation will rise soon. But strangely, inflation rates have continued to fall. The great disinflation continues.

Update December 2014:

The Big surprise in 2014: Spectacular gains in bonds despite Fed has ended QE. Bonds even beat equities in most mkts. pic.twitter.com/WAA9ZY3zrM

— Holger Zschaepitz (@Schuldensuehner) December 25, 2014

The Great Disinflation Continues, How Wonderful!

(Article originally written in November 2013, arguments still valid today, see latest updates above)

At the same time, the good news about the booming U.S. economy does not stop:

PMI Explodes Most On Record To 31-Month High; Biggest Beat Ever

ISM Services Index Soars to Record High

U.S. factory growth hits fastest pace in 2-1/2 years

Case-Shiller: US home prices rise at fastest pace since February 2006

Things seem to be clear: The United States is out of the woods, the Great Recession is definitely finished.

The end of monetarist theories?

Now it is time to quickly remove all these stimuli and hike interest rates, the economy could quickly overheat, … a monetarist might think.

“No, things are different”, the Fed responds. “Remember that we have a double mandate”:

- The first task is low unemployment. The unemployment rate is already quite low at 7.2%, but there are so many people working part-time and many others left the labor force, so why stop the monetary stimulus or hike rates?

- The second is inflation. Core CPI inflation is at 1.73%, and the even more important Fed gauge, the core PCE inflation is at 1.23%, well below the target that is between 2 and 2.5%.

Inflation in the euro zone is even weaker, it has fallen to 0.7%. Subsequently the ECB has cut interest rates to 0.25%.

Previously, Prof. Bradford DeLong called the St. Louis Fed’s chairman James Bullard a hawk, aka monetarist: an economic theory that stipulates that easy money leads to inflation. But things have changed and Bullard has changed:

…a 1970’s type inflation…it is not coming,” he said. “The monetarist camp, including my own staff … has got to re-examine some theories here,” he said. source Reuters

The great monetarist theory of the Nobel Prize winner Milton Friedman is still valid today, …. but not in developed countries.

We have just witnessed a perfect monetarist cycle in emerging markets, starting from fiscal and monetary expansion in 2009, over inflation in 2010 and overheating in 2011 to slowing in 2012 and 2013. Still today, the People’s Bank of China and the Banco do Brazil are fighting inflation and overheating.

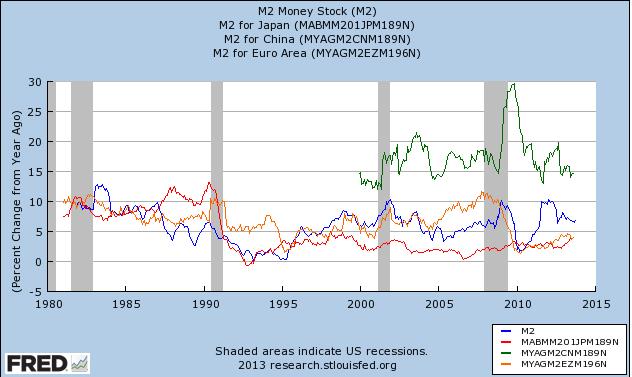

It is clear why: the supply of money increases by less than 3% in Japan (red line above) and Europe (orange line), but by more than 15% per year in China (green line), which is higher than the 10% seen in the U.S. or Europe in the 1970s and 1980s. 1970s style inflation in China and other emerging markets was only prevented because Chinese customers in the developed world want cheaper and cheaper costs. After the Great Recession, the U.S. and Europe are living in a period of slow income increases, high private debt, severe credit requirements and often weak demand for loans (the so-called balance sheet recession).

None the less, the Fed’s money printing, the massive increase in base money (M0), was not completely useless: M2 in the U.S. has been increasing by more than 7% per year since 2010. Unfortunately for the U.S., big parts of these funds poured into emerging markets and helped to increased loans, debt and spending there.

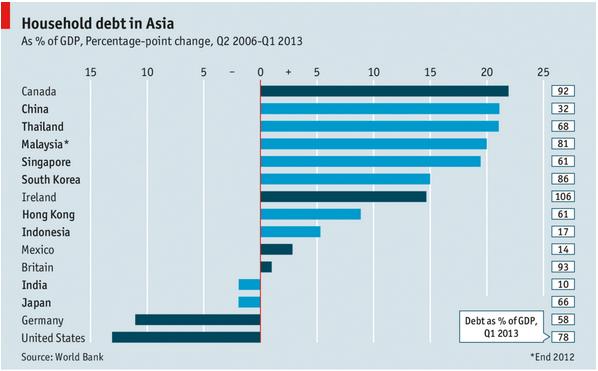

household debt in Asia (source the Economist)

The Great Rotation: The move out of bonds into stocks

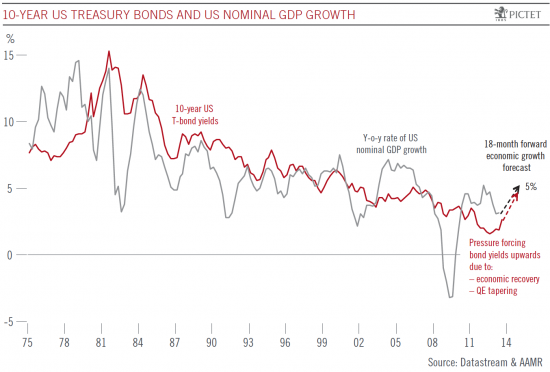

We judge that the “Great Rotation“, namely that investors move out of bonds and into stocks, will not last for very long.

Recently investors moved out of bonds in the expectation that inflation will rise soon. But strangely inflation rates have continued to fall. The great disinflation continues. - Click to enlarge

The demand for Treasuries was suddenly hit in June when tapering expectations came up. Due to weak but still high inflation and missing demand from Europe, emerging markets slowed. Their central banks had to sustain their currencies and sell Treasuries. As opposed to 2011, emerging markets like Indonesia or Brazil have current account deficits, India has a chronic deficit, while Malaysia’s housing- and spending bubble reduced the surplus.

And without surpluses, these countries cannot recycle capital inflows into dollars and Treasuries. But on the other side, current account deficits mean that emerging markets will be less a driver of global growth.

Europeans, like the Germans or Swiss, have massive surpluses. But they do not trust the Federal Reserve and do not buy Treasuries. They think that the Fed is destroying the U.S. dollar, they avoid currency risks and prefer to buy German or Swiss bonds at close to record-high prices.

But even the Chinese are able to cut costs and rising wages with innovation and negative producer price inflation. After US investors sold them, the Chinese the last protectors of US Treasuries. They are still expanding their trade surplus with the United States, even if their surplus to GDP ratio is falling: Chinese GDP rises more quickly than the surplus.

The Great Disinflation

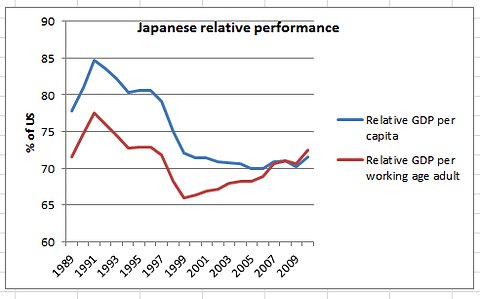

The Great Recession is finished but the Great Inflation of the 1970s will not restart soon. Central Banks are doing everything to avoid deflation to prevent the Great Depression of the 1930s or the Great Deflation between 1870 and 1890. According to Wikipedia:

[The Great Deflation from 1870 to 1890] had a negative effect on businesses in established industrial economies such as Great Britain while simultaneously allowing strong growth in the United States which was just beginning to industrialize.

In our times, replace “Great Britain” by “United States”, the “United States” by “China”, and the term “Great Deflation” by “Great Disinflation”.

The Great Disinflation1, is a period of lower and lower inflation rates that has lasted since the 1980s.

The following graph depicts the latest episode of the Great Disinflation and how inflation rates from year to year have become smaller – with the exception of Japan.2

Central bankers are not happy with this situation, they think that disinflation is far too close to deflation, a term that – Keynesians in particular – misleadingly – identify with recession. Just recently disinflation triggered an ECRI recession call.

Central bankers are not happy with this situation, they think that disinflation is far too close to deflation, a term that – Keynesians in particular – misleadingly – identify with recession. Just recently disinflation triggered an ECRI recession call.

Between 2000 and 2010, the Japanese have clearly shown that these two terms are clearly distinct (see details).

Recently investors moved out of bonds in the expectation that inflation will rise soon. But strangely inflation rates have continued to fall. The great disinflation continues. - Click to enlarge

Rising prices of services – in the U.S. by 2.4% YoY or in the euro zone by 1.2% show that even deflation of the headline CPI would not be a problem, but it is just an expression of innovation: goods become cheaper and cheaper, supply is rising more quickly than demand. Shale gas and oil are some examples.

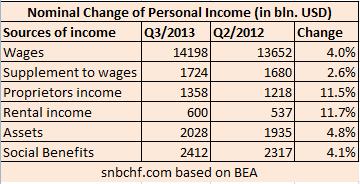

source BEA

The ones that are happy with disinflation are stock and company owners. Disinflation simply means that companies are able to cut costs, improve processes, innovate and increase margins, it means that wages do not rise or only modestly. It implies that employees do overtime without getting paid, in the fear that with global competition and so many unemployed people they will become redundant.

Disinflation is even better for stock owners, when masses of bond investors sell U.S. treasuries and move into equities. They are seeing gains of 20% this year with this sudden flood of funds. Real yields from 10 year Treasuries have reached values of plus 0.60% this year after minus 0.85% in December 2012.

And if profit margins are not high enough then companies just make workers redundant, just like in Italy where unemployment is poised to rise from 12.1% in 2013 to 12.4% in 2014.

Disinflation is wonderful!

Read also:

The ten drivers of disinflation.

Adam Smith Institute: Could Deflation Be Salvation?

Don’t sell economic stability to buy economic growth warns Tomas Sedlacek .

- To our knowledge, John B. Taylor was one of the first to introduce the term “Great Disinflation” when he described the success of tight monetary policy to finish the Great Inflation of the 1970s [↩]

- The BoJ managed to create temporary currency-induced inflation. Investors did what the BoJ wanted and devalued the yen because they were in the strong belief that inflation would soon restart, interest rates will rise everywhere – everywhere except in Japan. [↩]