With the introduction of the Outright Monetary Transaction Program (OMT) and “conditionality”, that requires austerity and implicitly the reduction of salaries in the European periphery, Merkel and German economists have created consequences similar to a gold-standard.

Originally written in December 2012, arguments still valid today

German economists: Supply-side, monetarist traditions and the euro crisis

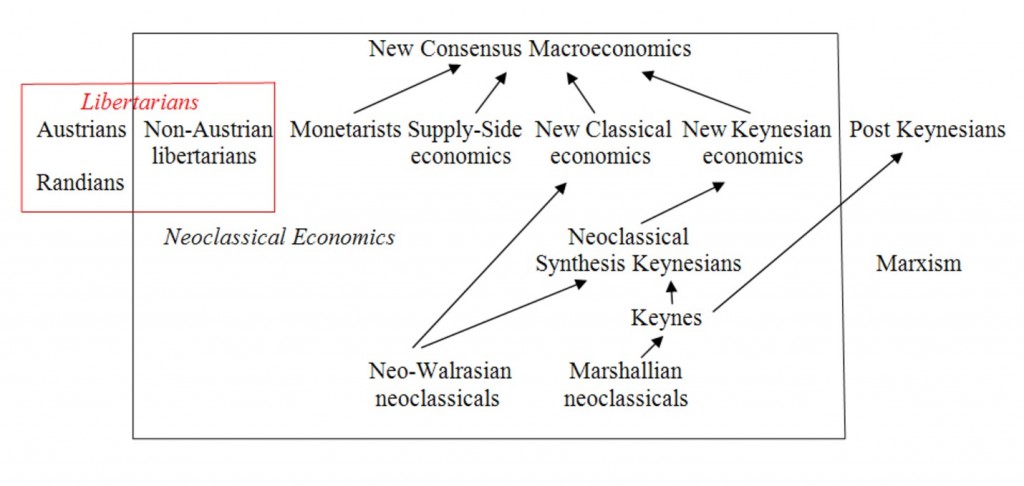

Most German economists aremonetarists, they prefer a gradual expansion of money supply, because they fear inflation. They are also supply-siders, whereas the English-speaking mainstream tends towards New Keynesianism (e.g. Krugman, Stieglitz and Eichengreen) and wants to stimulate demand and reduce unemployment. With the strict corset of the euro, this German approach implies a new gold standard. Money printing cannot heal a weak economy, hence salaries must be adopt downwards.

Both Germans and New Keynesians are contained inside the “New Consensus Macroeconomics”, but they are situated on two opposite sides.

Major economic schools (source) - Click to enlarge

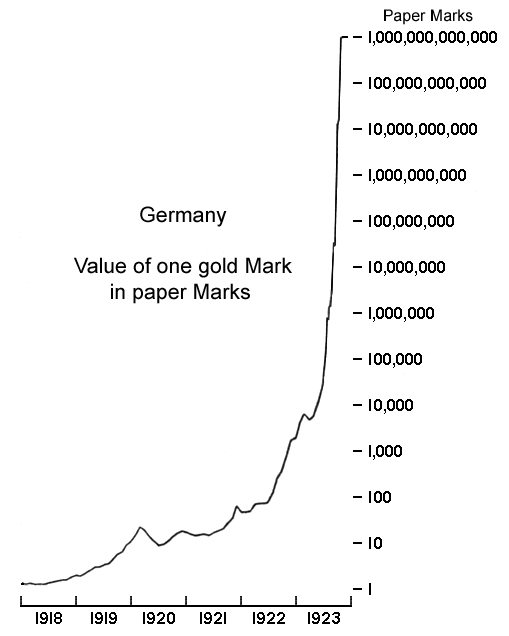

Monetarist Traditions: Hyperinflation in the 1920s

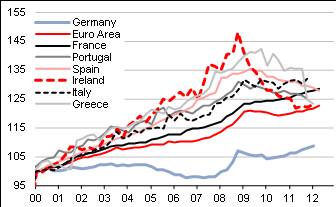

With ECB's OMT & "conditionality", that requires austerity and implicitly reduction of salaries in European periphery, Merkel & German economists have created consequences similar to a gold-standard. - Click to enlarge

Due to Germany’s bad experience with the hyperinflation in the 1920s, German economists strongly fear inflation and are therefore usually proponents of monetarist theories, a gradual expansion of money supply and limitations of public debt.

German economists: Supply-siders and the euro crisis

Central bankers, especially in the German Bundesbank, believe that the Euro crisis can only be solved by supply side reforms contained in the Stability and Growth Pact, reforms that were already successfully introduced during the Thatcher/Reagan era and in Germany between 2000 and 2004.

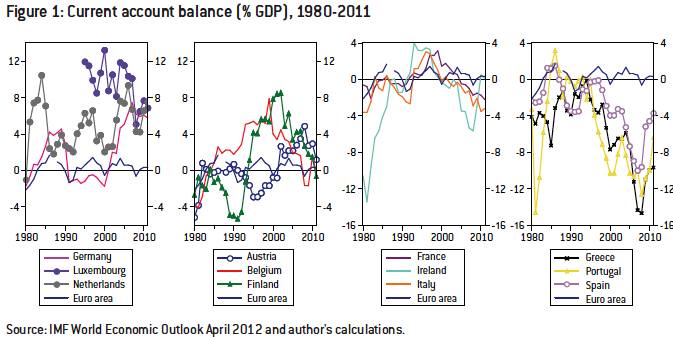

The idea of these neoliberal reforms is to reduce the big imbalances in current accounts achieved up to 2008. Germany had huge current account surpluses and the periphery huge deficits, which were financed by loans from German to peripheral banks.

Source Bruegel Think Tank

In the so-called “Memorandum of Understanding”, the official names of austerity programs, like the one for Spain here, one can always find a sentence similar to:

“A shift to durable current account surpluses will be required to reduce external debt to a sustainable level.”

A reduction of current account deficits or switch to current account surpluses can be achieved by a reduction of the (primary) deficits of the state, as stipulated in the fiscal compact. The reduction is achieved by so-called “adjustment programs”, that contain measures like higher taxes and austerity.

Global imbalances

Allowing the periphery to consume less, implies that German exports are reduced. And this weakens the euro and it makes German products for the United States and other countries more attractive. As of October 2012, the austerity measures have not affect the German trade balance, because a lower trade surplus with the periphery was balanced by a higher surplus with the US, the UK and Asia. A second important reason was that the Germans did not increase consumption and that they imported less.

The following graph shows the rising German trade surplus with the U.S., France and Asia, while the surplus is shrinking with the periphery.

Eurobonds and common responsibility

Merkel’s CDU does not want Eurobonds, for them, commonly issued bonds would mean that the PIIGS would not need to implement austerity as Merkel demanded in the Fiscal Compact. The Fiscal Compact wants a strong reduction of government debt and a balanced budget rule, which implies that the European states have to cut spending and implement austerity. To ratify the Fiscal Compact, including the balanced budget rule, is the precondition that countries can access the permanent European Stability Mechanism (ESM).

In December 2011 Germany and France advocated steps towards a fiscal union. According to Merkel, a fiscal union would include Brussels having to approve national budgets, a step still rejected by France. Some commentators even advocate that the logical step of a fiscal union would be a centralized finance ministry under an EU or German lead.

After France’s new president, Francois Holland, revealed his plans to cut the pension age to 60 years, Merkel has additionally introduced the idea of a political union including common economic policy and a loss of sovereignty towards Brussels. Only after that would a fiscal union be possible.

In summary:

Step 1) Stability and Growth Pact

Step 2) Fiscal Compact

Step 3) ESM

Step 4) Political union with common economic policy

Step 5) Fiscal union including a central authority to approve budgets.

Step 6) Banking union and eurobonds

Central bankers and economists, especially in the English-speaking countries, have very influential papers like “The Financial Times” or “The Economist“; also, the IMF are generally New Keynesians or New Classicals. They rely on economic principles that “overemphasize” economic interventions based on the short-run and on the demand-side.

Together with the French president they want a direct shortcut to the introduction of eurobonds and a banking union; they want Germany to pay the bill. At the same time their domestic countries, the UK and the US do not want to pay higher contributions to the IMF.

Merkel, however, understands that the periphery and France are not competitive enough. We will see in the following that this means “relative wage deflation in comparison to Germany.”

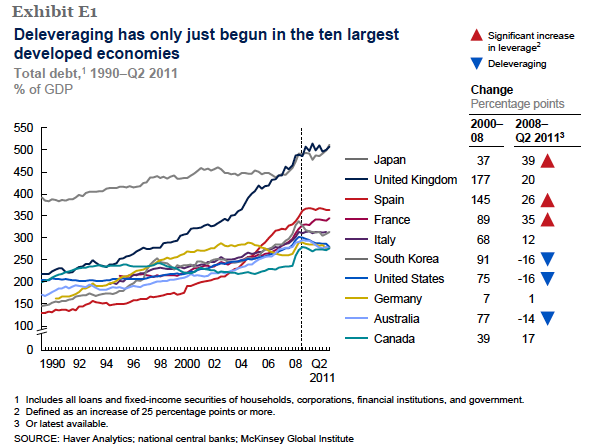

The Southern European de-leveraging phase has just begun

Economists, like the chief-economist of the Nomura institute Richard Koo, reckon that the United States, the UK and most other European countries are seeing a “Yang phase”, a de-leveraging phase, a so-called balance sheet recession of firms and individuals.

We commonly know the “Yin” phase, a period, when companies want to invest funds whenever they become available at sufficiently low interest rates. Keynesians and many central bankers think we are always in the “Yin” phase and firms will continue to invest and that the central banks just need to print money and then firms will invest.

But now, despite the huge availability of funds and record-low interest rates, firms are financing only the best projects to trustworthy borrowers. They know that other projects would not be profitable, because both consumers and companies want to reduce debt. This contradicts not only the Keynesian principle above, but due to high risk aversion also the Austrian economic principle, that low interest rates might trigger wrong investments.

Since 2011, since the end of the latest important bubbles, the Chinese, Brazilian and Northern European and French housing bubbles fueled by QE2, most parts of the world are deleveraging and not piling up higher debt any more. The current economic cycle even suggests that the United States has finished its deleveraging phase. But rising house prices do not imply the end of de-leveraging.

Deleveraging (source McKinsey’s “Debt Bible”)

There are just some developed countries that do not see a balance sheet recession, who are to afford higher debt and higher house prices, because they saw the bust of a bubble in the 1990s: these are Germany and Switzerland; countries where house prices still climb upwards. And this again strengthens the monetarist ideas in Germany and the fear of inflation.

Labor Cost Reduction: German economists are now implicit followers of the gold standard

Most German and Northern European economists want to preserve the euro zone as it is. But the only way for the weak euro countries to get out of their debt and become competitive, is to reduce labour costs and improve in terms of excessive tax rates, regulation and missing competitiveness.

Reducing labor costs is similar like in the gold standard, when it was not possible to devalue a currency, but weaker growth (as compared to other countries) needed to be compensated by lower wages, i.e. wage deflation, either in absolute terms or in relative comparison with Germany.

The economic asymmetry of core and peripheral countries during the gold standard era from 1870 to 1914 has been well researched and analyzed. A 2003 IMF working paper documented the reliance of the peripheral countries in the first decade of the 20th century on demand “which was highly sensitive to world income growth and mostly financed by capital imports from the core.”

Higher taxes and austerity leads to less consumer spending and less imports. This helps them to achieve current account surpluses.

Unfortunately austerity and less consumer spending also leads to less employment. When fewer people work, exports may weaken and the current account could worsen again. Moreover, the public debt/GDP ratio can rise: debt is only slightly reduced while GDP falls more than debt is reduced.

Interesting Reads on the euro and the gold standard:

Barry Eichengreen: Is Europe on a Cross of Gold?

The Economist: A trio of trilemmas The gold standard holds worrying lessons for the single currency

Will the periphery go through a deflationary spiral or only a balance sheet recession?

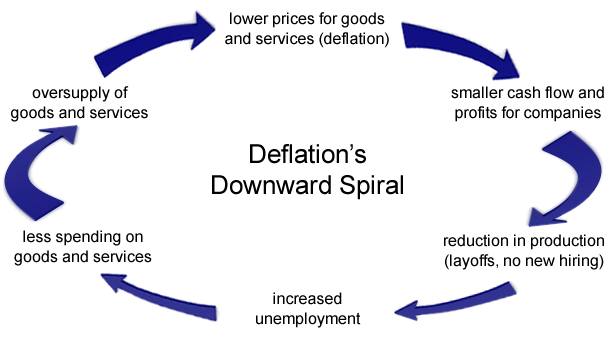

This implies for us that the periphery could go through a deflationary spiral during the next years. GDP may fall in most of the coming years. The deflationary aspect might be softened in the first years because many products will be still imported from Germany and elsewhere, from countries where prices are still rising. Therefore we think that initially (ie in 2012) the periphery will see a soft form of stagflation, negative GDP growth and despite of that, rising prices.

Deflation and lower wages in big parts of Europe and weak inflation in the very competitive Northern European countries implies that other countries like the United States or the UK are obliged to limit wage increases and/or to devalue their currency.

Given that Chinese wages and the Renmimbi have increased a lot since 2009 and the effects of the balance sheet recession implies that inflation pressures will remain subdued for a couple of years or maybe a decade even globally. We judge that after that decade, inflation pressures will start to be stronger, especially when the Chinese start to consume.

A group of 172 economists around Hans-Werner Sinn, the president of the IFO institute, have realized that the pressure on the periphery is too high and that they will not have a chance to exit this vicious cycle. They think that sooner or later these countries will leave the euro zone with even higher losses. They wrote an open letter against the attempts to make Germany pay for the huge debt of the PIIGS and their banks, a smaller group of economists is in favor of the ESM.

Harvard’s Niall Ferguson reckons that Germany will have to sustain the periphery with 8% of German GDP every year to go through this debt deflation cycle.

Several solutions, may it be the end of Euro in its current form?

We ask ourselves:

1) Will leaders finally react and accept losses in the German and Northern European official sectors preemptively – for example, with a quick introduction of the Northern Euro?

2) Or will Eurocrats kick the can and rule against the Spanish people for another ten or twenty years? And against German tax-payers that after these ten or twenty years will have paid a lot more than in a preemptive loss scenario?

3) Or will the monetary union finally break up when recession fears have become small and Germany shows higher inflation and the periphery low or even negative inflation?

4) Or will the United States use its reserve currency status again and finance the PIIGS with US trade deficits like the U.S. did in the 1980s and 1990s? And the wage gap between competitive Germans and less competitive Southern Europeans will finally close itself.

Update December 2014:

Solution 4 seemed to be the chosen one, Italian current account surpluses are increasing. The US is recovering and increasing its non-oil trade deficit. According to the Q3/2014 GDP release, German wage earners have received 3.6% higher incomes.

See more for