Our recent article on Fedcoin – a digital currency being considered by the Federal Reserve – revealed the sinister and pernicious reasons behind such a move.

This week’s episode of The Gold Exchange Podcast explores the topic further. In it, John Flaherty and CEO Keith Weiner discuss:

Addl description of episode

-

- A little-realized distinction between Fed credit and banking credit

- The Fed’s stated reasons for considering Fedcoin

- Why central banks will eventually have no choice but a digital currency

- The biggest problem within the dollar regime

Episode Transcript

John: Hello again and welcome to the Gold Exchange podcast. I’m John Flaherty and I’m here with Keith Weiner, founder and CEO of Monetary Metals. Today, we’re going to talk about the so-called Fedcoin. Keith wrote an article last week on the subject which has made a pretty big splash to date.

Keith, I was scrolling through the comments of one of the sites which can be fairly colorful, as you might expect. I think my favorite was “this could be 1984 and Mark of the Beast all rolled together and on steroids”. There was many of that ilk. But today we hope you can help us sort fact from rubbish. What we do know is that the central banks and governments around the world are exploring this. You quote in your article Janet Yellen, who said, quote, It makes sense for central banks to be looking at issuing sovereign digital currencies.

We already know that China is down the road a little ways in doing this. So in brief, Keith, what is a Fed coin or a gov coin?

Keith: Well, it will be the government issued, quote unquote, version of Bitcoin. But as soon as you say a government issued version that changes everything. So Bitcoin is, as everybody understands, decentralized. It’s not managed by a government or any other central authority in that sense. So what they want to do is sort of capture the, I guess it’s called halo effect, that it’s buzzy and cool and sexy and everything else. And create some sort of digital infrastructure that would not be…either wouldn’t be a blockchain or it wouldn’t be a blockchain based on, certainly not proof of work.

And then on that occasion, they can issue tokens that are legal tender dollars, not like a tether, which is supposed to trade at par for one dollar, but an actual dollar, and do it digitally that way versus the conventional system.

John: Well, but I’m confused. I thought we already have a digital currency. How would this be different? Precisely.

Keith: Yeah. I mean, there’s that. I think the difference is people don’t really think about the difference between having a dollar bill versus having a dollar in the bank. The dollar bill is the credit, it’s the liability it’s obligation of the Fed directly. And if you have a dollar in the bank, a bank deposit, you don’t actually have a dollar. You have the bank credit owing you that dollar. And because those two trade at par, and have traded at par for so many decades, people may overlook the distinction between the two.

So one is Fed credit, and one is bank credit. And they’re not the same. So the only time that people have direct Fed credit is when they own the paper cash. And everything electronic is banking system credit. So this would be a move, in a way to bypass the banks and issue electronic credit that would be accessible to the retail public. Whereas right now only the big banks are eligible to have an account directly at the Fed.

John: So…But how would they implement this? I mean, would people swallow this or would there have to be laws passed at the congressional level or does the Fed already have the authority to do this?

Keith: That’s an interesting question. I imagine lawyers at the Fed are busy poring over just how much authority do they have. I would imagine they could take the position – and I don’t know how this would play out in the courts or what the Supreme Court might say. But I would imagine they could take the position that since they have the authority to issue paper dollars, why wouldn’t that also include the authority to issue, essentially the same, but not in paper form, but in electronic form?

And if there’s anything that – not to tie this to Covid too much – but if there’s anything the last year has taught us, it’s that when a federal agency is rampant, aggressively taking for itself new powers in the name of whatever it is that they want to sell to the public, averting emergency or saving the children or whatever, that people by and large have accepted it. We accepted that the government divided us into two categories in 2020, those of us who were deemed to be essential, and those of us who were deemed to be non-essential.

The government took for itself that power. In the United States that never had that power previously. Communist countries, fascist dictatorships, they did. The United States they never had that power. But in 2020 they took that power. And as I like to say, we ragtag few of us, almost nobody really objected to that. So why not?

John: So what are the reasons that central banks are putting this forward? Going back to those colorful comments, it seems like everyone knows at some point Bitcoin is going to be neutralized by the Fed or government. Is this the Death Star for that task?

Keith: Well, I think there’s a lot of fear about what they might do to Bitcoin, but I think their stated reasons are – on the conservative side, the Jay Powells of the world – they have to respond to the competitive threat of Bitcoin and of China and all these things. As if the government competes against private businesses, which, of course, is absurd. If you look at the post office versus United Parcel Service, they don’t compete.

They pass a law that says you’re not allowed to carry first class mail. That’s not competition, that’s “we have a gun and you don’t”. So the idea that they’re doing it have some sort of competitive threat or whatever is ludicrous. On the left side, the Janet Yellen side, they’re saying, well, you know, it’s going to help address the problem, that we have so many unbankables. So this gets back to feed the children and all of that kind of sentiment.

But I think that’s grossly disingenuous. And I’m putting it kindly to say that. If concern is banking the unbankables, then there’s a really simple answer to that, which is lift the burden of regulation on the banks that renders the banks unable, either unable to profitably service the poor because the compliance is so expensive that it doesn’t make a lot of sense for the banks to open small accounts, or in some cases threatens the bank with so much liability. I’m thinking of anti money laundering, know your customer type regulation…that the banks don’t dare.

The poor people may tend to have a higher incidence of things that the banks have to flag under the regulation, forced to flag as higher risk. If they move multiple times, too many times within too short a period, that might be flagged as a money laundering know your customer risk. If they deposit checks that bounce, if they write checks that bounce, if they change jobs, if they have a job in the informal economy, they can’t really document their income.

Let’s say you take somebody who buys cars, fixes it up in their driveway or their front lawn and sells its 20 year old junker type cars. A lot of this informal economy kind of stuff makes the banks very nervous that the person might be committing tax evasion and the banks are held legally liable for this type of stuff under these laws. So if you really want to make these people bankable, lift the burden of regulation that forces the banks not to bank them.

So that’s…it’s just very disingenuous to cite reasons like that. It’s not the real reason.

John: Right. So as we try to do, let’s cut through the handwaving and propaganda and get back to……you stated in your article that there are two real reasons why central banks, in fact, will have no choice but to turn to this Fed issued crypto. Let’s go over those. What’s the first one?

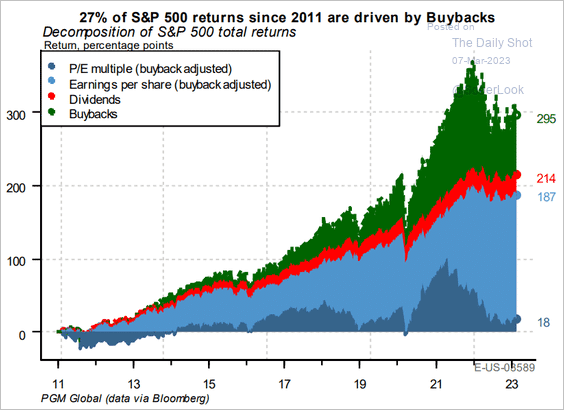

Keith: The interest rate is falling pathologically. It’s been falling for forty years. The central banks don’t know what to do about it. They’re wringing their hands.

I was at a monetary policy conference back in 2014. Bernanke was still chairman of the Fed. And what blew my mind was we had a number of speakers who were regional Fed presidents or retired former regional Fed presidents, and all of them pretty much had the same playbook of some variant of the Taylor Rule.

And in fact, they had, John Taylor, the Stanford economist who developed the Taylor Rule, that purport to tell them when to raise and lower interest rates based on unemployment and GDP and CPI and whatever. And they all pretty much agreed that, “Oh, yeah, Bernanke should have raised interest rates, whatever it was, 50 basis points six months ago. And I wonder why Chairman Bernanke isn’t raising interest rates?” And that’s when the final bit of my theory clicked for me, that…oh, I know why they’re not raising interest rates. They can’t. Interest rates are falling into a black hole of zero.

So anyway, it was baffling them at the time. And I think probably more than a little concerning. Here we are seven years later, they tried their brief experiment with hiking rates, were forced to lower it right back down. And now here we are basically at zero again. But they know that it’s headed below zero. And in Switzerland, it’s below zero. They were the first to have this pathology. Then Germany, Scandinavia, UK, Japan.

I mean, this drowning below zero. It’s like a viral disease that’s spreading. And it’ll come to the United States sooner or later, probably later. But it’s coming. And when it does, you have a problem as a central planner of money. And that is, do you have the commercial banks charge negative interest to their customers? Or do you somehow…so, if the commercial bank is taking your deposit and not charging you, but then whatever they put their money into is costing them because the interest rate is going negative, that means the bank is losing money on every deposit.

So you find some way to subsidize them or find some way to conceal that loss. Or at some point the commercial banks are going to be forced to actually charge interest to the account. As soon as they start doing that, and I don’t mean like one or two basis points, but once that starts to become significant. Let’s call it minus one percent interest. Then people have a pretty powerful incentive to withdraw the paper cash from their account. And that will then fuel the kind of run on the banking system that we haven’t seen since the 1930s.

And so how does the government respond to that? Well, they could find some way maybe to make the dollar bill lose its value. So even though it says twenty dollars on the face of it, it’s really worth nineteen dollars and 90 cents. But I don’t really see how you make that work. Or you ban cash and you go to some sort of digital cash, and I think that would be the first of the two reasons for why you’d create a Fedcoin, because then you can set the interest rate on the Fedcoin to be the same negative that you have for whatever the prevailing interest rate is in the economy.

John: The second reason that you state in your article has to do with feeding zombies. Can you elaborate a bit there?

Keith: Yeah. So the Federal Reserve…again, the difference between its stated purpose and its actual purpose: its stated purpose is to manage inflation and unemployment. That’s just window dressing. That’s the propaganda, really. I mean, I don’t think they really care about that at all. What they care about is enabling the government to borrow more than it otherwise could, so it can spend more and buy votes, and similarly enabling the government’s cronies to be able to borrow more.

But their prime directive would have to be: keep the major banks solvent. Don’t allow that cascade of defaults that would take down the banking system, including the big banks. You can’t allow that. Above all else, you must not ever let that happen. It came pretty close to happening in 2008, and I’m sure there was a lot of meetings at the Fed where they looked at everything that happened and said all those holes in the dike, we’re going to plug them. Every time a fuse burns out, we’re going to shove a copper penny in to replace it. We’ll never let that happen again.

And so if you look at the economy as a whole, most businesses and corporations are in debt. And the same thing with governments down to the level of county highway departments. Everybody’s borrowing and has borrowed over many, many decades to maintain the pretense that they have, the wealth that they don’t really have. And they can spend a lot more than they really should be able to spend. And all that that has to be serviced.

So everybody in the economy has to get their hands on enough dollars to service their debt. And so the only way to do that is to expand the number of dollars that are sloshing around freely in the economy. And what they’ve found is that one by one, all of the policy levers that they thought they had, turns out they’re pushing on a string. They lower the interest rate. But yet, commercial banks aren’t – they call it the money multiplier – they aren’t multiplying it the way they used to.

Last year, they actually eliminated any bank reserve requirements whatsoever. Used to be the banks had to hold a certain amount of reserves. That was a brake on the so-called runaway money multiplier inflation effect. Now they’ve eliminated that entirely. And what they’re finding is these things are not constraining the banks. There’s some reason why the banks are not able or willing to further push credit into the economy. And this frustrates the Fed because if the credit isn’t pumping freely, then the marginal debtor is going to be squeezed to default.

And so that term zombie is used by the Bank for International Settlements. The definition is slightly more complicated than that. But to simplify it down, a zombie corporation is a company that has profits that are less than its interest expense. Or to frame it the other way, its interest expense is greater than the amount of money it makes.

In other words, it can’t really service its debts unless it can get fresh, new, borrowed money every time it needs that to make a payment. It always has to be borrowing more in order to pay on the old. And its debt is growing.

So that exists by not only low interest rates, but by very forgiving credit market. According to the Bank for International Settlements, the last chart that I saw, more than 15 percent of all corporate debt out there is zombie debt. So there’s quite a lot of corporations that need Fed support in the form of just pumping more and more and more credit out there so that they can get some, so they can service their debts. And if they don’t, then they begin to default.

Their defaults will, of course, weigh on the balance sheets of their creditors. Some of those creditors will default, which will then hit their creditors and so on. And that’s the cascading domino scenario that we had in 2008 all over again.

Anyway, the bottom line is, if the commercial banks are unable or unwilling to push out the credit that the Fed wants to push out, then the Fed may bypass the commercial banks in essence. And say, “Fine, we’ll do it directly ourselves.” And then the Fed wouldn’t be as constrained as the banking system in terms of lending so they can achieve their goal.

John: So ultimately, this Fedcoin or any other version in any other central bank or government is just one more way, one more tool in the toolbox, to keep the fiat party going. Keith, how is gold the answer to Fedcoin?

Keith: Well, I guess you can answer that at the micro level and at the macro level. At the micro level, if you’re the saver, what’s the attraction to you to holding the Fedcoin? Well, especially if it’s going to have a negative interest rate. It’s profoundly unattractive.

There may be advantages to holding the Fedcoin versus having a bank balance. And I guess that you don’t have the risk of bank default if you hold the Fedcoin. But obviously gold…it’s a piece of metal. It’s not the liability of somebody else. You’re not dependent on someone else making good on it. And that’s the thing that makes people turn to gold. At the macro level, the problem with the dollar regime is that there is no extinguisher of debt.

The debt must grow exponentially. It must grow by at least the total amount of interest accrued during the year. Not actually more than that, because you have to see to it that the marginal debtor gets enough. And in order for the marginal debtor to get enough, you have to expand credit by a heck of a lot more than just accrued interest. So it’s exponentially growing total debt until it blows up. Any exponential trend eventually fails catastrophically. They don’t fail gracefully. So there’s no way out of that.

And people say, well, we’ll pay off the debt with inflation. I say no, au contraire, monsieur. Inflation is the process of borrowing more. So, yes, the dollars you owe, each individual dollar you owe, may be worth a bit less, but you owe exponentially more of them. That’s like saying that the solution to getting out of the hole that we dug for ourselves is to dig deeper. No, you can’t get out of a hole by digging deeper.

You cannot get out of debt by inflating, by borrowing more. The only way to get out of debt is to move to a monetary system in which it is possible to extinguish a debt. And so, if I owe you a thousand dollars and I hand a thousand dollars over, I’ve was just merely shifted the debt. Now the Fed owes you the money and I’m out of the debt loop.

But if I owed you an ounce of gold and I hand you a one ounce gold coin, the debt goes out of existence. The debt is cleared.

So the solution is to go to a gold standard to make it possible to clear debt. And therefore it doesn’t continue to accumulate exponentially with all of the economic malaise that that accumulation causes.

John: Well, that’s all the time we have today to enjoyed this episode on Fed coin. Thank you for joining us on the Gold Exchange.

Full story here Are you the author? Previous post See more for Next postTags: Featured,newsletter,The Gold Exchange Podcast