|

I actually wanted to focus on this yesterday but confirmation wasn’t forthcoming until today. So, it ended up being a broader note on the dollar which only included some mention of Brazil in passing. Still a worthwhile couple of minutes. There were rumors that Banco (central) do Brasil was intervening or was going to intervene in its local currency markets, which may be an important signal. More of swaps that aren’t really currency swaps (which you can read about here). In lieu of reading the whole thing, here’s a brief summary:

In other words, since the central bank “swap” reduces the futures price of dollars in relative comparison to the spot price, there is a greater incentive for banks (both Brazilian and foreign) to borrow US dollars on foreign markets and import them to take advantage of the cupom cambial spread. The swap isn’t really a swap in the conventional sense since the central bank is only swapping dollar indexed securities – deliverable in reals. In short, it is the old central bank axiom of getting the “market” to do your dirty work for you. It has since been confirmed that the central bank sold 20,000 contracts for a small notional $1 billion in today’s trading, not yesterday’s. The dollar amount isn’t the matter, more symbolism than anything particular with where things stand in Brazil. |

Dollar Correlations, 2017-2020 |

My intent in only mentioning this last night was to raise a poignant issue, to ask the question, why now?

Banco had intervened on a short-term basis once more recently, back in November. What I didn’t add to yesterday’s discussion was the details of what’s been going on down there in South America. Thus, I hope, it should become clear(er) why I wanted to wait for confirmation before jumping into Brazil’s deep and confusing weeds once again. With the real taking out records, it invites idiocy. First up for a Thursday, Brazil’s President Jair Bolsonaro who said the dollar was “a little too high”, a sentiment with which America’s President Donald Trump wholeheartedly agrees but is powerless to enact. Next, Banco President Roberto Campos Neto repeatedly emphasized in his televised interview, preaching calm, that the real was a floating currency and this is just what happens sometimes. Except, no, typically when currencies float down to record lows as Brazil’s has done (again), the countries attached to them are experiencing some high and noticeable level of danger and turmoil. It’s not what floating currencies do, this is what troubled currencies do as a reflection of a troubled system. To which then Economy Minister Paulo Guedes entered the fray, declaring confidently that his weaker currency is “good for everyone.” It doesn’t take long before someone says it. Stimulus, dammit! It’s all very confusing for several reasons. The first is what many people might not know about Brazil and emerging markets. It’s been two years since hearing much about them, that April-May 2018 period when suddenly, while the US and Europe were “booming” mind you, some sort of unexplained currency chaos erupted across this section of the world to interrupt all the fun (and massive inflation). And then it disappeared – at least from the news reports. Those falling currencies, that rising dollar, didn’t. In fact, it has been a rough couple of years in these places even if the exchange values didn’t grab and hold the world’s attention. The rest of the planet, though, suddenly had its own mess to worry about; the trouble had traveled inward and plunked down right at home. |

Europe Industrial Production, 2016-2019 |

| Almost like this 2018 EM crisis was a canary dying in an increasingly poisonous dollar mine, an early warning about that global “boom.” As everyone now knows, it was already a globally synchronized downturn underway.

OK, so that much became common knowledge in 2019 well after the fact; including a recession scare here in the US by August. Now, though, as the mainstream narrative tells it, it was all a big misunderstanding, a false alarm and much to do about nothing. Ever since September the world economy has been moving upward again. As Federal Reserve Vice Chairman Richard Clarida said, and I’m going to repeat this phrasing so many times over the coming months, global headwinds and disinflationary pressures are and have been abating. Those worldly disinflationary pressures are what comes out in Brazil’s real. |

USD/ Brazilian Real, 2017-2020 |

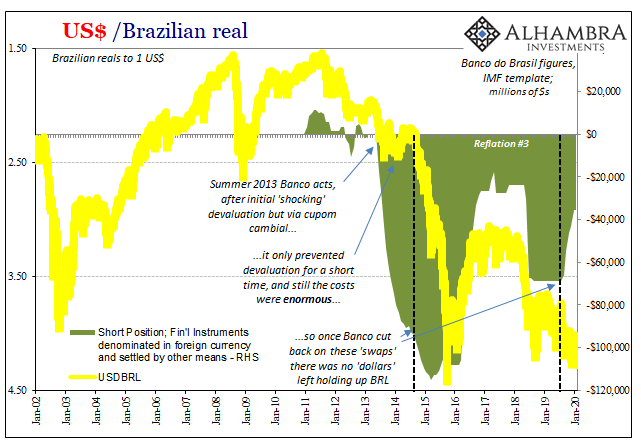

| What have the monetary authorities at Banco been doing since last summer? Exactly what you’d have expected of them. Central bank officials have been following the narrative like good little Economists. Like 2013, in the middle of 2018 they had reacted to the currency crisis by deploying “swaps” (and a large dose of moral suasion; fancy, tough talk; see above).

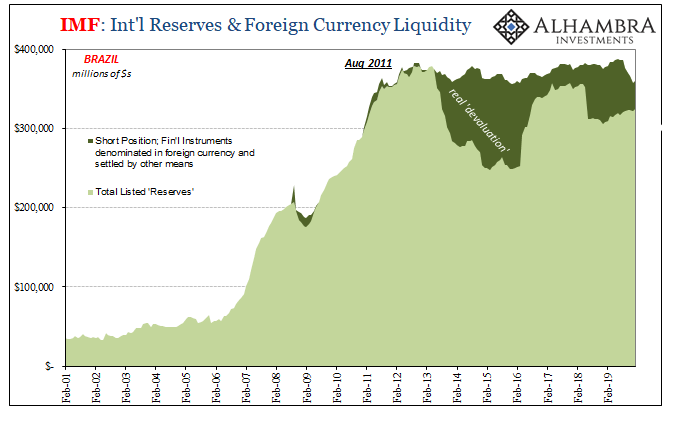

But because Jay Powell (and Richard Clarida) has said everything’s back to normal again, Banco has actually been paying those off…with reserves. Going back to last August, Brazil reports (to the IMF) that its outstanding balance of these swaps (reported as “financial instruments denominated in foreign currency and settled by other means; e.g., in domestic currency”; see below) has declined by a little more than $33 billion. |

IMF: Int'l Reserves & Foreign Currency Liquidity, 2001-2019 |

| At the same time, total reported forex reserves have fallen by $27 billion. |

IMF: Int'l Reserves & Foreign Currency Liquidity, 2001-2019 |

| What that says is two things: first, authorities really did believe that the dollar was done rising, or at least done rising against the real, and that the eurodollar system would start pumping “dollars” back into Brazil again; second, it didn’t happen.

And, all-too-predictably, because this is just what took place the last time (2014-16), BRL started to decline without the central bank to prop it up with its cupom cambial interference. Without the central bank to effectively subsidize domestic banks in their quest for offshore dollar funding, banks in Brazil don’t seem too eager to go more “short” in front of the very real possibility of renewed (or unabated) dollar strength. Which is like a short squeeze on that synthetic short position. The last thing you want to do in front of one of those is get deeper into it. Thus, BRL has been falling again – despite the “all better” signals classified as abating disinflationary pressures and now two more currency interventions in daily trading. All leading away from the promised land, instead to a record low currency exchange (rising dollar). |

USD/ Brazilian Real, 2002-2020 |

The short version is this: stop listening to people like Richard Clarida. It’s a message directed at a general audience as well as advice for central bankers in Brazil (and elsewhere around the world). He may speak of disinflationary pressures but he has no real idea what they are, where they are breaking out, or when they are and have abated.

All the Fed’s horses and all Fed’s men are still trying to put repo back together again – five months later.

The guy (Clarida) is just talking in exactly the same way as Brazil’s Economy Minister Paulo Guedes, to portray confidence no matter how unsupported and preposterous. What everyone has finally figured out, except Guedes, apparently, is only that when the dollar goes up it’s bad for everyone. Especially in places like Brazil.

The dollar is still going up. That’s the main takeaway from all of these things going on. In many ways, all those that really count, it didn’t actually stop going up (even if the exchange value did temporarily; it’s what the system is doing behind the visible numbers). Not in September nor the months that followed. It’s just showing its ugly head most visibly in the EM world again.

What might that say, potentially, about the next few months outside of EM’s?

Full story here Are you the author? Previous post See more for Next post

Tags: Brazil,currencies,dollar short,dollar shortage,economy,EuroDollar,eurodollar system,Federal Reserve/Monetary Policy,Markets,newsletter,real,richard clarida,rising dollar