Political jockeying between the world’s major powers is intensifying in space, making the development of rules on conduct in space more critical than ever. To achieve this, Switzerland wants to play the role of “bridge builder” in space, as on Earth.

In November 2021, Russia destroyed an obsolete Kosmos satellite by launching a missileExternal link 480 kilometres into space. When the Soviet-era structure exploded, hundreds of thousands of pieces of debris went flying into low Earth orbit, forcing staff on board the International Space Station (ISS) to take cover.

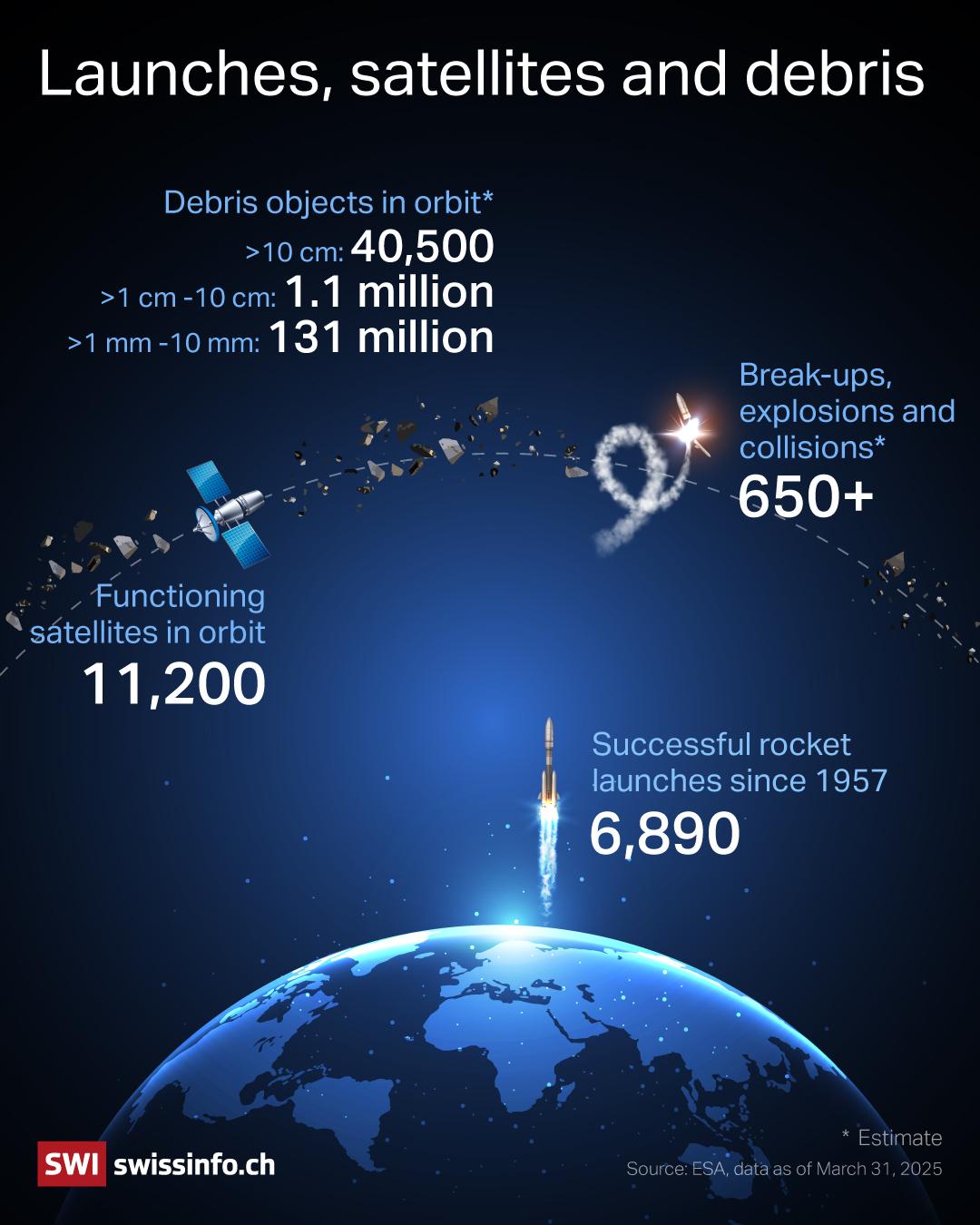

Back on Earth, the test served as a reminder that, with roughly 10,000 (and counting) active satellites hovering above us, space infrastructure is vulnerable to catastrophic damage – whether as a deliberate target or following a collision.

“The orbital environment has to be shared by all space actors,” said Clémence Poirier, a cyber defence researcher at the Center for Security Studies at the federal technology institute ETH Zurich. Due to high velocity, a single piece of debris measuring just a centimetre in diameter can destroy a satellite weighing a few tonnes, she explained. “A physical incident can eventually impact us all.”

Space-going nations large and small are grappling with this reality. Switzerland, which calls itself “one of the 20 most active nations in space” based on government investment, has drafted its first law on space operationsExternal link, now under consultation.

Its ambitions are not purely economic and scientific. As space becomes increasingly crowded with both commercial and state players, Switzerland wants toExternal link “promote responsible behaviour in space and serve as a mediator and bridge builder where possible”.

More

Opinion

More

Why Switzerland’s proposed space law matters

Space as ‘an operational domain’

The rivalry between the United States and the Soviet Union that dominated the dawn of the space age 65 years ago no longer defines space today. More than 70 countries now haveExternal link their own space agency, with 16 of them capable of space launches.

More satellites than ever are being launched – Elon Musk’s Starlink company alone accounts for nearly 7,000 – while investments in space reached a record $70 billion (CHF62 billion) in 2021 and 2022, the World Economic Forum (WEF) reportsExternal link. By 2035, the WEF estimates the space economy will be worth some $1.8 trillion.

Switzerland wants a piece of this pie. Although it doesn’t have its own space agency, it is a founding member of the European Space Agency (ESA) and wants to “shape European and international space activities” – which is why it’s building a legal framework for the country’s 250 start-ups, companies and universities engaged in this sector.

The Swiss government invests around CHF305 million ($345 million) in space activity a year. This includes contributions to the ESA (totalling CHF600 million over three years), the European Organisation for the Exploitation of Meteorological Satellites, Horizon Europe and national space sector activities.

This investment, it says in its 2023 Space PolicyExternal link, flows back into the domestic economy, including providing for some 1,500 jobs in the high-tech sector.

At the same time, it is keen to support the development of space governance. Basic international principles governing activity in outer space already exist. Some can be found in the 1966 UN Outer Space TreatyExternal link, which says all states are free to explore space for peaceful purposes, and that none can stake a claim of sovereignty or place weapons of mass destruction in orbit.

In recent years, however, space nations have realised there is a pressing need for additional regulation to tackle emerging threats. Space debris is just one of them. Defence alliance NATO considers space “an operational domain”, as some militaries gain the ability to target infrastructure in space, such as with anti-satellite missiles.

Major space powers are also developing dual-use technologies, said Poirier: for example, robotic arms designed to remove space debris – a civilian mission – can also be used for military purposes, such as eliminating an adversary’s satellite. Cyberattacks are another growing threat, she added. Russia is suspectedExternal link of having conducted one at the start of its 2022 invasion of Ukraine against a satellite network that provides internet access in Europe.

However, many high-level attempts to agree on new rules have been unsuccessful. More than a decade ago, the EU drafted an international code of conduct in space that ultimately failed to get key states – including the US – on board. More recently, following Russia’s downing of its own satellite, the United Nations General Assembly adopted a resolution calling for a moratorium on destructive, direct-ascent anti-satellite weapons testing. Of the countries that have demonstrated this capability – Russia, China, the US and India – only the US backed the resolution.

Refraining from destructive missile tests is an example of what Switzerland considers “responsible behaviour”, said Natália Archinard, who holds the space portfolio at the Swiss foreign ministry. But the UN resolution shows the lack of global consensus on this question – differences that Archinard said reflect the divergent national security and commercial interests of the big players in particular.

A civilian or military space programme?

These players are, above all, China and the US – strategic competitors on Earth now locked in a rivalry in space. Bill Nelson, head of US space agency NASA, has saidExternal link the two countries are “in a space race”.

NASA is ramping up Artemis, its project to get back to the Moon, and is preparing for a mission with a crew to Mars. More than 50 countries, including Switzerland, have signed the US-led Artemis AccordsExternal link, which reinforce the commitment to cooperative space activities for peaceful purposes, as set out in the Outer Space Treaty.

More on the US and China’s orbits of influence on Earth:

More

More

What Switzerland can do about the US-China rivalry

For its part, China, which aims to become a space superpower by 2045, is collecting samples from the far side of the Moon. In conjunction with Russia, it is developing an International Lunar Research Station, bringing onboard some 13 partner countries, including South Africa, Venezuela and Thailand. It has also built its own space station, Tiangong, having been shut out of the ISS by the US Congress for security reasons.

Nelson, however, has accused China’s civilian space programme of also being a military one. Of the 700 Chinese satellites in operation, 245 are used for military purposes, US intelligence agencies claim. The Chinese, however, insistExternal link their space ambitions are peaceful and that they are committed to developing international space governance.

Rather than being in competition, these rival space projects could be complementary, said Victoria Samson, a space security expert at the Washington-based Secure World Foundation, an NGO dedicated to space sustainability. As a signatory of the Outer Space Treaty, China is likely to be pursuing its activities on the Moon according to principles similar to those in the Artemis Accords, Samson said. To allay any doubts, she added, China should publish them.

Amid these tensions, Switzerland wants to act as bridge builder in outer space, a role that Archinard said is “very much aligned with the [country’s] traditional role in multilateral diplomacy”. It is already active in several UN-led discussions on space governance. There, the Swiss are working pragmatically and “step by step” on new principles, Archinard said – some legally binding and others not, which would prevent armed conflicts being fought in space.

For example, on the UN Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (COPUOS), where Archinard leads the Swiss delegation, the country helped to get the adoption of 21 guidelinesExternal link on the long-term sustainability of space activities. It also contributed guideline D2, encouraging technological solutions to manage space debris and reduce collision risks.

As bridge builder, Switzerland can “help facilitate dialogue and build common understanding around certain topics”, Archinard said. “[Or] make proposals which we believe could gain consensus from all sides.”

Learn more about Switzerland’s good offices role in diplomacy:

More

Need a diplomatic messenger? Switzerland is eager to help

Poirier agrees that Switzerland can “extend [its] already recognised expertise in mediation into another domain”. She even sees a role for the country in developing space traffic management, or a global system for satellite operations akin to air traffic control in aviation, to help avoid collisions.

“Switzerland is a neutral country that doesn’t have military satellites or counterspace weapons, so it doesn’t have a stake in favouring one operator over another,” she said. “So it could have a mediating role putting operators in contact to de-escalate disagreements, especially when sides like the US and China that want to avoid a collision struggle to talk to each other.”

Samson also believes that, if they act in good faith, countries can ultimately reach agreement on space governance. “The important thing is to keep having these discussions.”

Edited by Lindsey Johnstone/vm/ts

More

More

More

Our weekly newsletter on foreign affairs

Tags: Featured,newsletter