One of President Trump’s proposals for his new term is to abolish the federal income tax and replace it with tariffs as the primary revenue source for the US federal government. In a brilliant rhetorical move, he suggests implementing this through abolishing the Internal Revenue Service and replacing it with the “External Revenue Service,” claiming that the tariffs collected by this new agency would be financed by foreigners rather than Americans. This sure sounds like a good deal.

Trump has claimed that “tariff” is the most beautiful word in the English language, even more so than “love.” Perhaps it would be if it were a device by which one could costlessly extract funds from foreigners. But is a tariff capable of doing such a thing?

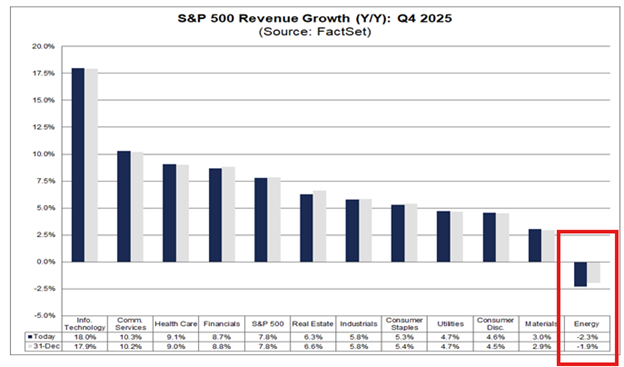

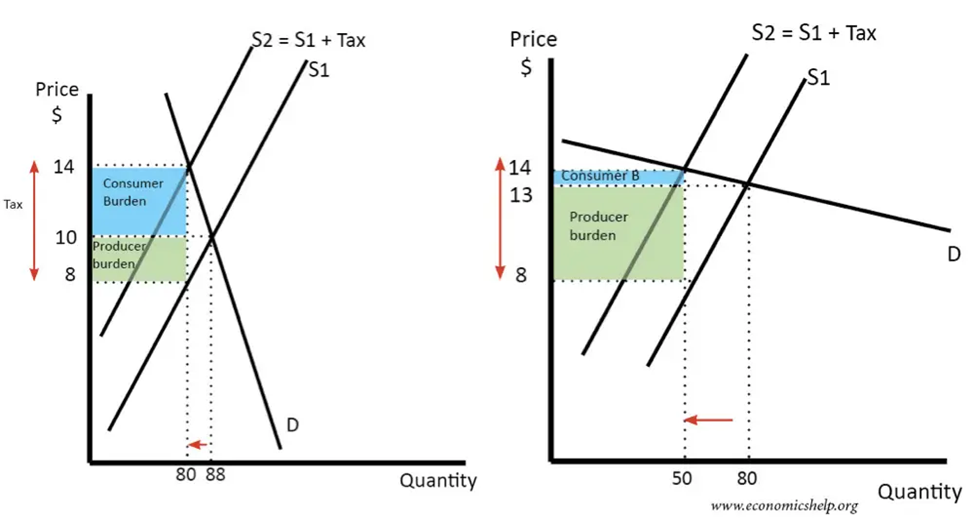

Standard microeconomic analysis tells us that the economic “incidence” of a tax (that is, who really pays what portion of it) is not necessarily who statutorily collects it. In other words, just because sales tax is collected by the seller who then pays it to the tax man, this doesn’t mean that it is the seller paying the whole tax. Rather, the incidence of the tax depends on the relative elasticities of the buyer’s demand and the seller’s supply. A greater portion of the tax will be borne by the party whose demand (or supply) is relatively inelastic, as shown in the figure below.

So is AOC right when she says the recently threatened tariffs on Colombian exports to the US will be paid by Americans? Not if she means that the tax will be exclusively paid for by Americans, but yes, if she means to say that at least some will be. The US is a big market for Colombian exporters—it is unlikely that Colombian coffee producers, for example, could halt all their exports to the US, attempt to sell it all elsewhere, and receive the same amount of revenue. In other words, the supply curve of Colombian for exports to the US is upward sloping, rather than flat. However, unless that supply curve is vertical (in which case, the quantity of Colombian coffee supplied to the US would be completely unresponsive to changes in price), at least some of the incidence of a tariff on Colombian coffee exported to the US would be borne by US consumers. The only other possible way that the tariff would be fully paid by Colombian exporters is if the demand curve of US consumers for Colombian coffee is horizontal, which would mean that any increase in price would lead to Americans not buying any Colombian coffee at all. As such, any tariff would have to be fully paid by Colombian exporters.

To reiterate: there are only two (unlikely and perhaps even impossible) circumstances under which the incidence of tariffs would fall fully upon foreigners:

- The supply curve of the foreign exporter is vertical (perfectly inelastic)

- The demand curve of US consumers for a particular country’s exports is horizontal (perfectly elastic)

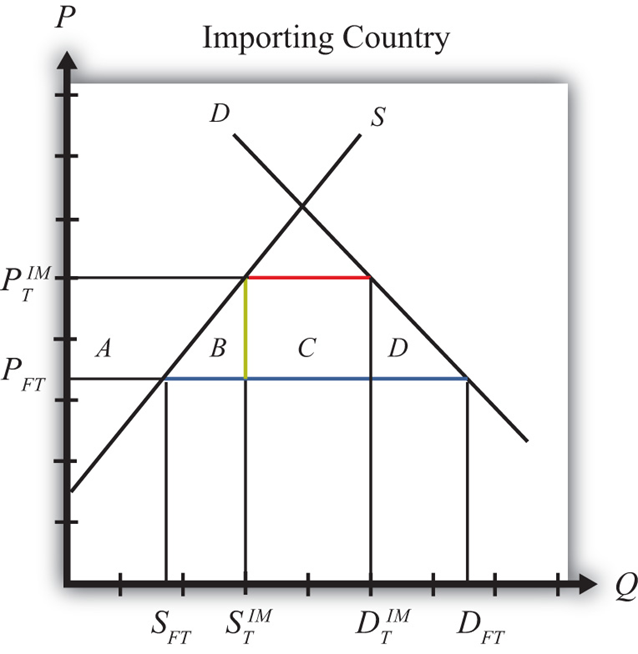

A far more plausible scenario in the realm of international trade is a relatively elastic supply curve. Indeed, a model commonly presented in international trade textbooks analyzes the effect of a tariff in a “small” country, which is assumed to lack the heft to sway world markets through its citizens’ decisions to buy or abstain from buying, and thus faces a horizontal world supply curve:

In this case, the reason the importing country faces a horizontal supply curve at PFT is because consumers in the importing country have to compete with the rest of the world’s consumers, and if they aren’t willing to pay at least PFT, exporters can find plenty of other consumers who are willing to pay that price. As such, if the importing country’s government imposes tariffs on this good, the full burden of the tax will be on domestic consumers because the only way exporters are willing to sell in that country is if they receive at least PFT.

Something you’ll also find in a typical international trade textbook is a model analyzing the effects of tariffs in a “large” country, meaning that demand in that market is large enough such that exporters cannot find just as many willing buyers elsewhere. Under such circumstances (and if supply and demand curves are drawn in a certain way), in this model it’s possible for the large country to “benefit” on net from tariffs—that is, the total dollar value of deadweight losses from the tariff in terms of losses in consumer welfare and production inefficiencies is outweighed by a sufficient amount of the tax falling on exporters. (However, this net “benefit” treats taxpayer dollars in the hands of the government as just as valuable as taxpayers being able to keep their money.) But even in this optimistic scenario (in the real world we could not even determine whether such an “optimal tariff” had been achieved), it is still the case that tariffs are being at least partially paid by domestic consumers. There is no free lunch.

One further thing to emphasize (as noted by Robert Murphy in a recent episode of The Human Action Podcast) is that there is a conflict between the goals of having a tariff protect domestic producers on the one hand and be revenue-generating on the other hand. In the former case, the end of having a protective tariff is making imports sufficiently expensive that domestic consumers will choose to buy from a domestic producer. The more successful the tariff is in this regard, the fewer imports there are and, therefore, the less tariff revenue there is. If it is 100 percent successful and no imports are purchased, then there is no tariff revenue.

Gary North agreed with Trump that “tariff” sounds better than “sales tax”:

The politicians of the national state come before the voters and propose sales taxes on goods that cross into the nation from abroad. The politicians are careful not to describe these sales taxes as sales taxes. Too many voters are tired of paying the existing level of taxes, let alone a new tax. So, the politicians call these sales taxes by a new name: tariffs.

But there is nothing magical about tariffs. They are taxes and they are paid by you.

Full story here Are you the author? Previous post See more for Next postTags: Featured,newsletter