The United States and Switzerland have experienced remarkable highs and bruising lows in their post-war relationship. Their disputes, in particular, have tested core Swiss principles such as neutrality.

In a speech at an Independence Day party in Zurich in 2023, American ambassador Scott Miller captured the essence of relations between Switzerland and his country. “There is no issue of global importance where our nations are not leading together,” he said, “or where we are not sharing our common values to make things better.”

Recent history is full of examples of the two countries collaborating over a shared interest in a stable, rules-based international system. One highlight was Switzerland, a neutral country, rolling out the red carpet for talks between US President Joe Biden and Russian President Vladimir Putin amid geopolitical tensions in June 2021.

Another high point came when Swiss and American authorities created the Fund for the Afghan People in 2022 to inject some of the Afghan central bank’s reserves frozen in the US back into the Afghan economy.

But the countries have also had major disagreements. The US, for instance, has criticised Switzerland for refusing to allow the re-export of Swiss-made arms to Ukraine, a position the Swiss government is maintaining for reasons of neutrality.

Below is a selection of events that have tested Swiss principles such as neutrality, showed the benefits of working together – and revealed the power imbalance in the bilateral relationship.

Nazi gold and dormant assets sour relations

Switzerland did not officially take part in the Second World War, but its economic ties with Nazi Germany strained relations with the US.

During the war, Bern gave the Third Reich a loan to buy war materiel and, together with private banks, bought gold from the Nazis, part of which was plundered in occupied states. One recent estimate put the value of “Nazi gold” in Swiss hands at CHF1.7 billion ($2 billion).

To compel it to stop trading with Germany, in 1941 the US froze Swiss gold reserves in New York. But Switzerland declared itself politically and economically neutral, continued trading with Germany, and limited transactions only towards the end of the war. In 1946 Switzerland agreedExternal link to pay CHF250 million into an Allied fund for reconstruction in Europe in return for its frozen assets.

The affair, however, resurfaced decades later. In 1995, the World Jewish Congress filed a class-action suit in New York claiming Holocaust victims and their heirs were being denied access to bank accounts in Switzerland that had lain dormant since the war.

Negative media stories on the Alpine nation soon followed, as US President Bill Clinton requested an investigation into gold looted by the Nazis in occupied countries. In Bern the government created a taskforce while parliament set up an independent commission, led by historian Jean-François Bergier, to study the country’s actions during the war. A 1997 US State Department report even claimed Switzerland had been the “Nazis’ banker”.

“The dormant assets affair disrupted US-Swiss relations for several years,” writesExternal link the Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.

In 1998, the banks settled with Holocaust victims and their heirs to the tune of $1.25 billion. Although the two countries put the matter behind them, their conception of the dispute diverged, says Sacha Zala, director of Dodis research centre on the history of Swiss foreign policy. “For the US, it was about getting a deal done, but for the Swiss, it was traumatic for their self-image [as a neutral country],” he says.

US pressures Switzerland on Cold War rivalry

Right from the early days of the Cold War, Switzerland came under intense pressure to again set aside its neutrality and accept America’s position in the Western rivalry with the Soviet regime. One memorable episode came after the US imposed an export embargo on the Eastern bloc in 1951. “The American government used all means available to secure Switzerland’s participation,” writes the Historical Dictionary.

More

More

Our weekly newsletter on foreign affairs

Washington threatened economic sanctions, so Bern had no choice but to accept the informal Hotz-Linder agreementExternal link to cut trade in strategic goods with Communist states.

At the time, Switzerland bypassed a formal treaty just so it could preserve its neutrality on paper, says Zala. Yet by agreeing to the export controls, the country had effectively taken a position in the Cold War and sided with the West. The deal, says Zala, shows the disproportionate power the US wielded in its bilateral relations.

Switzerland helps US defuse crises as a protecting power

A 1961 agreement for Switzerland to represent US interests in communist Cuba marked a peak in the bilateral relationship, according to Dodis. This protecting power mandate, which lasted 54 years, allowed small Switzerland to play an outsized roleExternal link in defusing Cold War tensions, including the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis.

Today Switzerland’s sole remaining mandate for the US is with Iran, in place since the US broke off relations with the Islamic Republic in 1980. Again, Switzerland has acted as an important go-between during major crises. During the 444-day hostage situation that began at the US embassy in Tehran in November 1979, Swiss diplomats helped to evacuate released hostages and ensure the well-being of those who remained. They also kept communication channels open and helped to negotiate a deal.

More recently, Switzerland has facilitated US-Iran prisoner exchangesExternal link and allowed the two to communicate at critical moments, including when Tehran launched a major drone and missile attack on Israel in April 2024.

For a small country, Switzerland’s good offices role “can open doors in Washington, but it only goes so far”, says Zala, who points out that the Alpine country can’t resolve all its differences with the US even with this privileged access.

US-Swiss FTA talks fail – but trade booms

A free trade agreement with the US has long been on Switzerland’s wish list. Martin Naville, the former head of the American Swiss Chamber of Commerce, likens an agreement to a life insurance policy in case the US and the European Union sign an FTA of their own.

The US and Switzerland seriously flirted with the possibility of a trade deal in 2006. But exploratory talks broke down when it became clear the two would not compromise on agricultural protectionism and genetically modified organisms (GMOs), saidExternal link Naville, who was involved in the talks.

Switzerland tried again but failed to get renewed interest in a deal under the business-friendly president, Donald Trump.

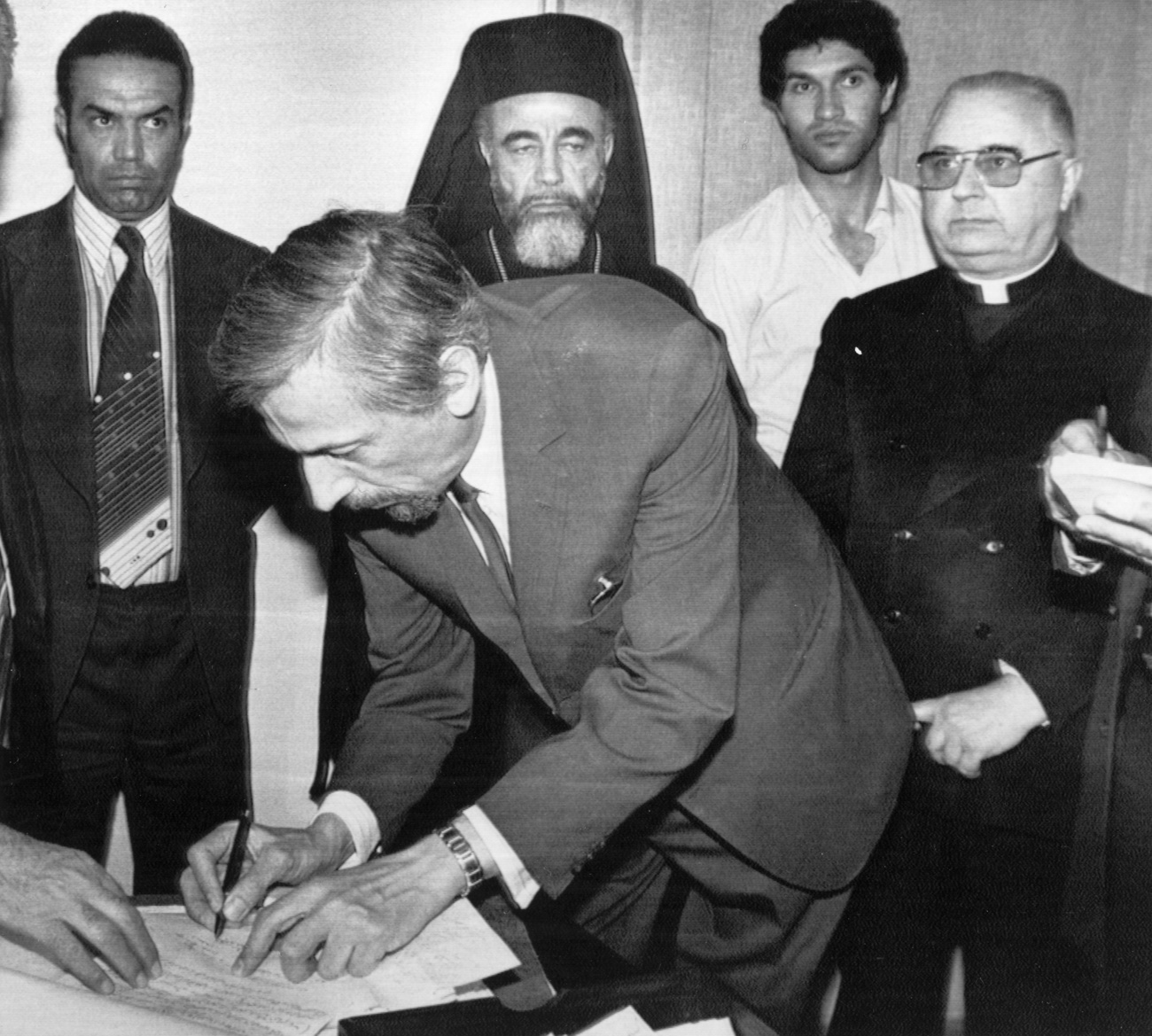

With Biden’s administration calling FTAs a relic of the 20th century, the Swiss are instead negotiating sectoral and technical agreements with the US to reduce trade barriers. When the first such deal was signed in 2023 – for mutual recognition of inspections at pharmaceutical production sites – Switzerland’s top economics bureaucrat, Helene Budliger Artieda, revealedExternal link the Swiss government still wanted an FTA with the US.

Do or no deal, bilateral trade is booming. Today the US is Switzerland’s second-most important trade partner, after Germany. The US is also Switzerland’s largest foreign investor.

US tax-evasion lawsuits dilute Swiss banking secrecy

After the economic crisis of 2008, US authorities accused Switzerland’s largest bank, UBS, of helping wealthy American clients dodge taxes back home, sparking a major rift between the two countries.

To avoid criminal prosecution in the US, UBS had to reveal the identities of around 250 American customers, pay a fine of $780 million in the US and take full responsibility for helping clients evade taxes.

The affair significantly diluted Swiss banking secrecy – today banks are held to confidentiality only within Switzerland. It also prompted the US to go after other Swiss banks: more than 100 of them have since paid over $7.5 billion in US fines; two banks have collapsed.

The outcome, says Zala, shows the leverage the world’s biggest economy holds over Switzerland, itself a strong economic performer.

“In international relations, there’s a dimension of power tied up with trade and commercial interests,” he says. “This power is absolutely gigantic in the case of the US. If you don’t comply with them, then you can’t do business with them.”

Edited by Virginie Mangin/ts

More

More

Sister republics: what the US and Switzerland have in common

More

Tags: Featured,newsletter