|

Stocks don’t vanish when sold; somebody owns the shares all the way to the bottom. These owners who refuse to sell because they have convinced themselves the next dip will be the hoped-for resumption of the bullish trend are called “bagholders.” Trends are tricky. Humans anticipate the present conditions will continue on into the future. In economics and finance, we call this continuation a “trend.” Trends continue until something fundamental changes and the trend takes a new course. If asset prices, credit, sales, jobs, tax revenues and profits are all expanding, we call this trend “bullish.” If the economy and asset prices are contracting, we call this “bearish.” People are much happier in bullish trends because they’re making money without any effort as the assets they own are going up in value. They feel wealthier and so they borrow and spend more money, which furthers the expansion. This self-reinforcing feedback reverses in bearish trends as people feel poorer so they borrow and spend less, reducing demand for goods and services. People don’t like feeling poorer so bear trends are not favored. The focus of those in power is to reverse any bear trend into a bull trend and extend the bull trend as long as possible. But eventually every bull trend runs into limits. People borrow the maximum their income can support and then they borrow more to bet that assets will continue rising in value. This flood of money pushes assets up far beyond their previous value, disconnecting them from the fundamentals of yields, replacement value, etc. As valuations soar, those who bought the assets find that most of their profits are capital gains from the rising value, not from income. So they buy more assets, expecting the trend of soaring valuations to continue more or less indefinitely. But valuations only rise when demand from buyers exceeds the supply offered by sellers. Once the valuation bubble reaches a peak, sellers who decide to take profits or sell to pay down debt exceed demand from new buyers and valuations decline. This is called “the credit cycle” or “the business cycle” but it’s really a cycle of human nature: when gains are effortless, we want to increase our gains, so we increase our borrowing, leverage and risk to buy more assets. |

|

| “Investment” becomes pure speculation unmoored from fundamentals. Eventually valuations, leverage and debt all reach extremes and so valuations, debt and leverage all start to contract.

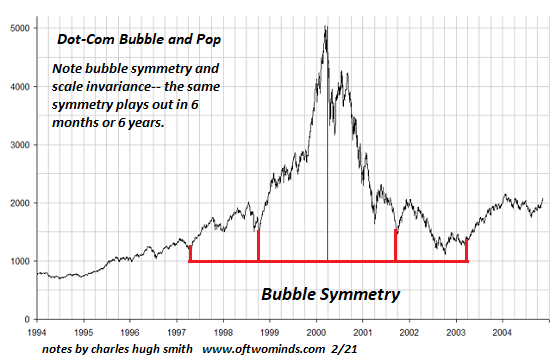

The euphoria of getting effortlessly richer is replaced by the fear of getting painfully poorer, and so buyers turn into sellers. This becomes a self-reinforcing feedback: as valuations drop, more people decide it’s time to sell. Once valuations decline, owners who bought more stocks with debt are forced to sell by margin calls. What makes this transition interesting is that humans are reluctant to let go of a trend that has been good to them. The natural tendency is to think /assume / hope that the asset that is sinking will stop sinking and recover its former During expansive trends, this “buying the dip”–buying more of an asset whenever it drops–is rewarded, as every downturn is brief and the uptrend soon resumes. But once the trend has reversed, “buying the dip” is no longer rewarded, it is punished, as valuations continue sliding. Experienced traders look for evidence of this transition because they’ve learned the hard way that those who cling on to the idea that the bull trend is basically forever because The Powers That Be want it to be forever end up losing most of their wealth. Inexperienced traders have great difficulty believing the effortless gains are ending, as the majority of traders are still bullish and the financial media is also bullish. It’s easy to find convincing reasons to believe the bullish expansion is simply taking another brief pause. Money manager Jeremy Grantham has long studied speculative bubbles. Here is Grantham’s perspective: “I wrote an article for Fortune published in September 2007 that referred to three “near certainties”: profit margins would come down, the housing market would break, and the risk-premium all over the world would widen, each with severe consequences. You can perhaps only have that degree of confidence if you have been to the history books as much as we have and looked at every bubble and every bust. We have found that there are no exceptions. We are up to 34 completed bubbles. Every single one of them has broken all the way back to the trend that existed prior to the bubble forming, which is a very tough standard.” |

|

| Grantham sees the current bubble as three simultaneous bubbles overlapping into a super-bubble. The US stock, bond, and housing markets are all three standard deviations from their historical average. Grantham says there have been only four super-bubbles in history: in the US in 1929, 2000, and 2006, and in Japan in 1989.

It’s interesting to debate why the current super-bubble can’t pop or won’t pop, and argue whether this or that will cause the bubbles to pop. Nobody knows who will be right: those calling for a new bull trend to new highs or those calling for a crash as the super-bubble finally pops. I titled this exploration of trend “calm before the storm” because the transition from bullish expansion to bearish collapse is ultimately an internal battle within bulls hoping for a quick return to effortless gains. They have a great many reasons to want the rally to resume, and few reasons to willingly accept that holding onto the assets that made them so much money will now only decrease their wealth. This tug of war is generally calm. The storm starts when the first “vital few” sellers (4% of owners, if the Pareto Distribution holds) cause 20% of owners to start selling. This avalanche of selling–the storm–triggers behavioral changes in the 80%. Stocks don’t vanish when sold; somebody owns the shares all the way to the bottom. These owners who refuse to sell because they have convinced themselves the next dip will be the hoped-for resumption of the bullish trend are called “bagholders.” Every experienced trader has been a bagholder. The reasons and psychology are always the same: we are reluctant to let go of bullish trends and our belief that a long-term change of trend is unlikely. Maybe the trend is still bullish and it will never be interrupted by the storm of a trend change. But maybe the trend has already changed, and the storm clouds are gathering just over the horizon. |

|

Full story here Are you the author? Previous post See more for Next post

Tags: Featured,newsletter