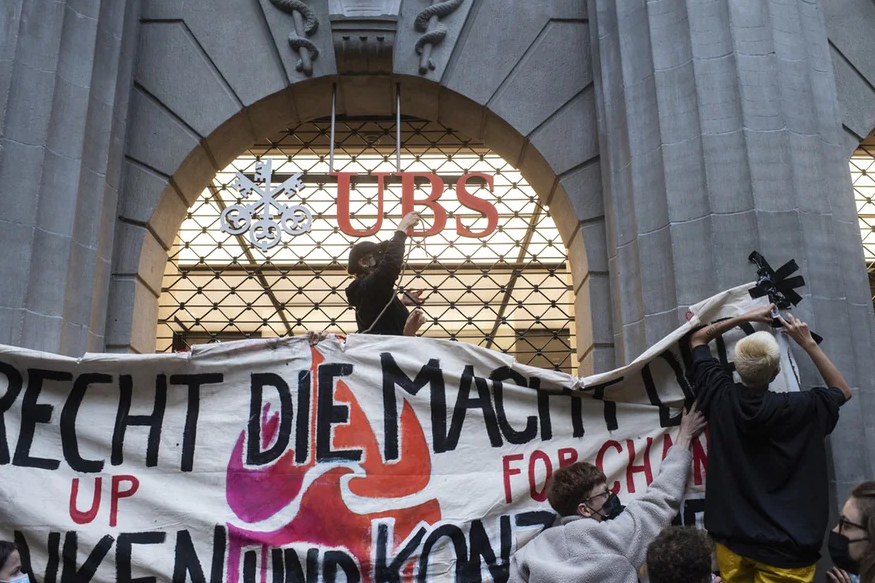

Major banks, like UBS, are coming under increasing pressure to clean up their investments. Keystone / Ennio Leanza

As businesses were gearing up for the COP26 climate summit in Glasgow last year, one of Europe’s larger banks released an update on how it planned to do its bit to combat global warming.

Switzerland’s UBS group said it had become a founding member of the new Net Zero Banking Alliance, a UN-convened club of mostly western banks committed to decarbonising their portfolios. “We’ll publish a comprehensive climate action plan later this year setting science-based targets, including intermediate milestones,” UBS said.

This was in April. But there was no new action plan by the end of the year. The bank says it is now aiming for March.

One explanation for the delay is that the climate programme had to fit in with a broader strategic vision for UBS, which its newish chief executive, Ralph Hamers, is due to unveil in February.

But the lag also reflects a wider industry dilemma: the vast volume of work that banks are confronting as they grapple with net zero commitments that are set to make 2022 a year when financing fossil fuels grows more visible — and troublesome — than ever before.

Hazy definitions

“It’s a huge task,” says Jörg Eigendorf, head of communications and sustainability at Deutsche Bank. Membership of the Net Zero Banking Alliance requires it to calculate and model the carbon footprint of a loan portfolio worth billions of euros, which it will disclose by the end of 2022. “That will bring much greater transparency and scrutiny from regulators, politicians, investors and the general public,” says Eigendorf.

You might not think this will matter much, considering the trend towards green financing. Renewables and other climate-friendly ventures received more bank-issued bonds and loans than the fossil fuel sector for the first time in 2021, and more backing is in the pipeline.

Deutsche Bank, JPMorgan Chase and HSBC are among more than a dozen banks whose annual green financing commitments now outstrip their 2020 support for fossil fuels, says Autonomous, a financial research firm.

Definitions of green financing can be generous, but the direction of greenward travel seems clear — except for one thing. Banks may be turning on the taps for green finance but they are far from closing them for fossil fuels.

Fossil fuel investments

The world’s 60 largest private sector banks have put more than $3.8 trillion into the oil, gas and coal sectors since the 2015 Paris agreement, according to NGO research. And a lot has gone to oil and gas companies with big expansion plans.

With no sign of rapid change, banks face a double difficulty in exposing their fossil financing to more scrutiny — and charges of climate villainy — without showing how they might eventually wind it back.

In theory, the problem should be solved by a group like the Net Zero Banking Alliance, whose 98 members account for more than 40 per cent of global banking assets. They have to set out plans for zeroing out emissions. The trouble is the brutal maths.

Scientists have established it is much safer to limit global warming to 1.5°C. So human-made carbon emissions, much of which come from burning oil, gas and coal, should nearly halve by 2030 and fall to net zero by around 2050. Long story short: the world has to quickly wean itself off fossil fuels, that make up about 80 per cent of the energy mix, and ditch plans to dig up more.

Fanciful idea?

Banks have reduced backing for coal over time. But very few net zero alliance members have issued detailed plans showing how and when they might wind down support for oil and gas as well — the rules give them several years.

One exception is France’s La Banque Postale. In October it said it would exit oil and gas industries completely by 2030, the same as its deadline for coal. Goldman Sachs, JPMorgan Chase and other banks in the alliance that have begun to publish more detailed net zero plans have yet to follow its lead.

They may stand to lose more business than the French bank, but some analysts think loss of brown financing could be offset by green growth. Rising demand from a swelling green sector for loans and other banking services could be worth an extra net $2.3tn a year for decades, says Autonomous.

Privately, some bankers acknowledge the risk of sticking with companies determined to keep generating a lot of emissions, but little bank revenue, especially if rival lenders start staking out profitable green turf. Others say it is risky to be a first-mover in the absence of meaningful carbon pricing or other government policies to level the financing playing field.

And what’s the point of listed banks exiting fossil fuels if private investors facing less scrutiny step in? Private equity firms are estimated to have invested more than $1 trillion in the energy industry since 2010, mostly in fossil fuels, which underlines where the net zero financing battle is heading next.

“Publicly traded banks are not the end of the problem,” says Mike Hugman, director of climate finance at The Children’s Investment Fund Foundation. Private equity investors should demand that all companies they back have meaningful climate action plans, he says.

Not long ago, this idea would have sounded fanciful. But times are changing fast. Just ask a bank.

Copyright: The Financial Times Limited 2022

Full story here Are you the author? Previous post See more for Next postTags: Environment,Featured,newsletter