The flurry of rulemaking stems from a concern that climate change poses a threat to financial stability. Whether this is true or not is hard to say. The data are shoddy and climate-risk reporting is largely voluntary. Firms tend to cherry-pick the most flattering numbers and methodologies. The reporting seldom reveals anything about a firm’s risk in the future—which is where the financial threats from climate change mostly reside.

Many watchdogs are pinning their hopes on the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD), set up in 2015 by the Financial Stability Board (FSB), a global group of regulators. The TCFD has recommended a reporting standard made up of 11 broad categories, from carbon footprints to climate-risk management. Regulators like it because it focuses on material risks rather than environmental impacts, and because it asks for information about firms’ future plans. That includes “scenario analysis”, in which a company’s strategy is tested against potential futures, such as a hotter world or higher carbon prices.

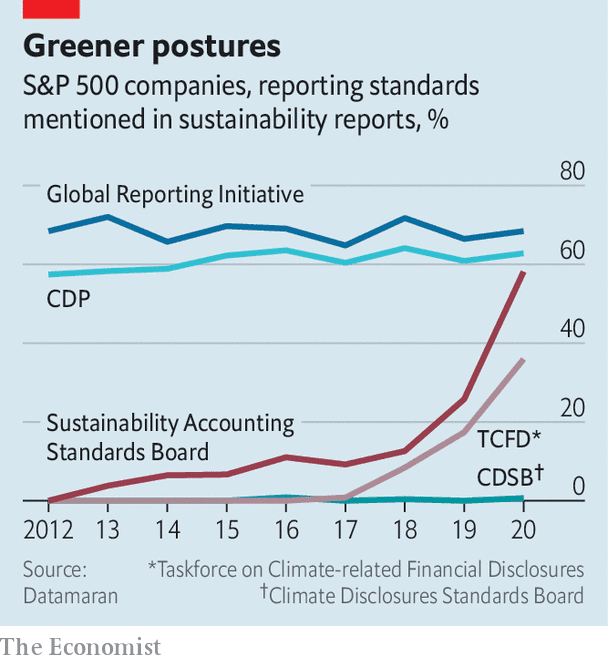

| These qualities also appeal to financiers. Financial firms make up almost half of the 1,800 or so companies that back the TCFD‘s recommendations. Together they hold assets worth over $150trn and include the world’s ten biggest asset managers and eight of its ten biggest banks. Their clients and regulators are egging them on to adopt the standard, so the financial firms in turn are prodding companies to do so, too, causing an uptick in its use (see chart).

Not all companies are happy about this. It means compliance with one more ESG measure, and a tricky one at that. Many bosses claim their firms lack the expertise to do climate-based scenario analysis (the TCFD’s recent 133-page how-to guide may help). Only 7% of big firms disclose such exercises, according to a review of 1,700-odd companies by the TCFD. Those that do often use different scenarios, making their efforts hard to compare . Another problem is that disclosures may scare off investors. This, of course, is the point. But until reporting is mandatory for everyone, firms risk being punished for being early adopters. That is the evidence from France, which made climate-risk disclosures obligatory for asset managers, insurers and pension funds in 2016. A study by its central bank compared those firms with French banks and non-French financial firms. It found that the firms which had to disclose climate risks held 40% fewer bonds, stocks and other securities in fossil-fuel firms by value than those that did not have to disclose risks. |

Greener postures |

Such a shift may drive up capital costs for polluting projects and lead to fewer emissions. But more climate disclosure will not by itself cut carbon, notes Remco Fischer of the UN Environment Programme. Regulatory climate risk can, in theory, be mitigated by moving carbon-heavy assets somewhere with laxer environmental rules. And sophisticated risk assessments do not always result in decarbonisation. Last year AGL Energy, an Australian utility, published an analysis of scenarios. The one it has chosen to follow involves keeping one of its coal-fired power stations open until 2048. ■

For more coverage of climate change, register for The Climate Issue, our fortnightly newsletter, or visit our climate-change hub

This article appeared in the Business section of the print edition under the headline “Telling all”

Full story here Are you the author? Previous post See more for Next postTags: Featured,newsletter