The Federal Reserve this morning slashed the target federal funds rate by 0.5 percent today. According to CNBC:

economy remain highly uncertain and the situation remains a fluid one,” he said. “Against this background, the committee judged that the risks to the U.S. outlook have changed materially. In response, we have eased the stance of monetary policy to provide some more support to the economy.” |

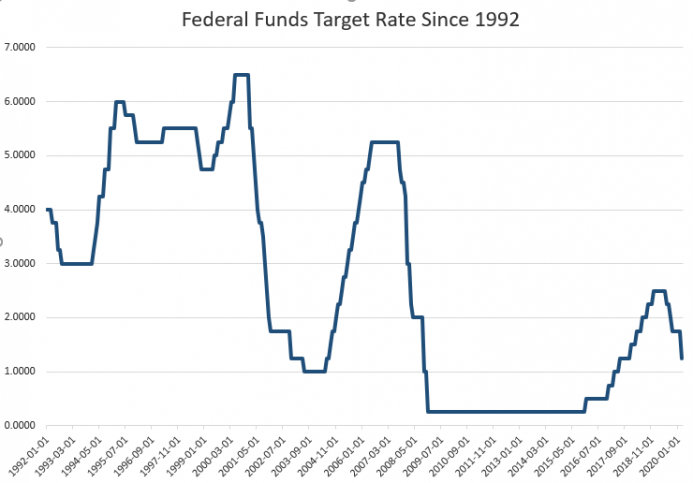

Federal Funds Target Rate Since 1992 |

| With this change, the target rate now is back down to 1.25 percent. The target rate was last at this level during mid-to-late 2017, in the midst of several rate hikes as the Fed dared to allow rates to climb. During that period, the Fed repeatedly declared the US economy to be “moderately strong” or “strong,” although it proceeded with extreme caution even then.

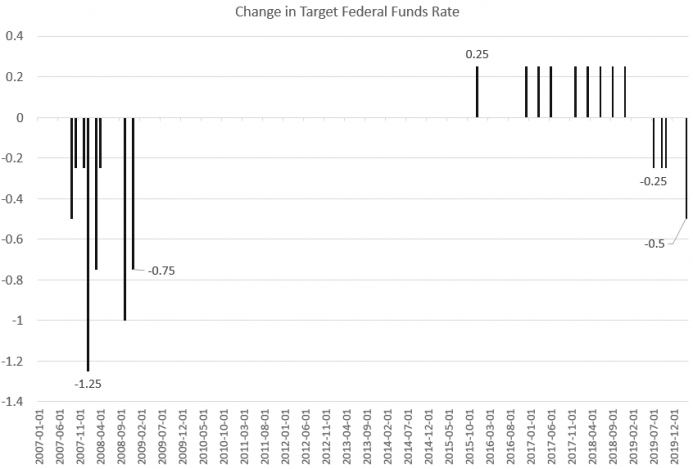

Since July 2019, however, the Fed has returned to cutting the target rate, fearing that the economy is weakening. Then in August 2019, it began pumping liquidity into the repo market in an effort to shore up hedge funds and banks. All the while we’ve been assured everything is fine. Today’s rate cut of 50 basis points, however, is the largest rate cut since December 2008, in the midst of the aftermath of the financial crisis. |

Change in Target Federal Funds Rate, 2007-2019 |

This Is Fine!

The Fed’s announcement comes only days after Powell announced on Friday that “The fundamentals of the U.S. economy remain strong. However, the coronavirus poses evolving risks to economic activity.”

But if fundamentals are so strong, why the need to enact the biggest rate cut in more than a decade?

This is the usual flip-flopping we’ve been witnessing for years from the Fed. The Fed announces that the economy is stable and strong, but then it refuses to raise the target rate. Or the Fed may even cut the target rate, just as “a precaution.”

Those with particularly astute memories may recall the unfortunate similarity between Powell’s statement and John McCain’s declaration in September 2008 that “The fundamentals of our economy are strong, but these are very, very difficult times.”

In cases like this, it may be prudent to completely ignore the first part of the sentence about economic strength. The only information of importance lies in the second part of the sentence—the part about “difficult times” or “evolving risks.” The similarity between these two patronizing statements, of course, does not mean that Powell will be proven wrong in the same time frame as McCain. The Fed has become quite adept at creating new bubbles when old ones appear to weaken and at propping up market confidence with new bailouts, such as we saw with 2019 rescue of the repo markets.

So, the fact that we’re seeing some downturns now does now necessarily mean a full blown recession is right around the corner. Although the coronavirus outbreak presents serious problems in terms of the supply chain, the problems in Asia could actually drive more capital to the safety of the US and the dollar, postponing the economic reckoning in the US into the future yet again.

After all, other aspects of Fed policy show that the days of stimulus are far from over. The Fed is now nearly back to peak levels in terms of its portfolio, signaling that it is not at all willing to let the market have its head in terms of pricing Treasurys and a variety of other assets. The Fed knows there’s just not enough demand out there to soak it all up. As Doug French recently pointed out, after all, the private banks still haven’t shed all their shadow inventory, even in this booming economy.

But yet again we’re left with the question: if the Fed is slashing interest rates while “fundamentals are strong,” what must it do when things aren’t so “strong”? Negative rates and QE seem to be the logical next step.

On the other hand, the Fed has apparently not yet hit the panic button when it comes to interest paid on excess reserves (IOER). Today, it announced a cut to “the interest rate paid on required and excess reserve balances” down to 1.10 percent. The IOER is another tool the Fed uses to manage how much money leaves bank reserves, thus entering the real economy. The higher the IOER rate paid, the lower the opportunity cost banks face in keeping reserves locked up in reserves. In January, the interest paid on these reserves was up to 1.60 percent. The gap between the target federal funds rate and the IOER rate can be interpreted as an indicator of how badly the Fed wants to push reserves out the door of the banking system. In late 2019, the gap had been 20 basis points. But since late January, the Fed has narrowed this gap to 15 basis points, suggesting less urgency in the need for liquidity. Today’s cut to 1.10 percent keeps that gap at 15 basis points. This is a more moderate position than if the Fed had cut the IOER rate even more than than fed funds rate.

Full story here Are you the author? Previous post See more for Next post

Tags: newsletter