We’re way overdue for a sell-everything recession, one that the Fed will only make worse by pursuing its usual policies of lowering interest rates and goosing easy money.

As I noted last week, central banks, like generals, always fight the last war–until the war is lost. The global economy is careening into recession (call it a “slowdown” if you are employed by the Corporate-State Media), and while we don’t yet know just how deep and wide this recession will be, we can make an educated guess that it won’t be a repeat of any of the previous five recessions: 1973-74, 1981-82, 1990-91, 2001-02 or 2008-09.

Recessions triggered by energy or financial crises tend to be short and shallow as the crisis soon eases; recessions caused by structural imbalances tend to be enduringly brutal. Many recessions are structural, but the triggering event is a short-term crisis.

Some recessions savage specific sectors but leave most of the economy relatively unscathed. Others disrupt virtually everything, even the generally impervious-to-recession government sector.

Let’s run down the general outlines of the previous five recessions. If you’ve lived long enough, you’ve experienced the suffering firsthand. Younger readers will have difficulty relating firsthand, but understanding the dynamics is the goal here, and so direct experience is a bonus, not an essential.

1973-74: the Oil Shock to the U.S. economy as OPEC raised prices and punished the U.S. for supporting Israel in the 1973 Yom Kippur war created havoc–long lines at gas stations and a sharp downturn (a.k.a. recession). Though the economy supposedly recovered statistically in 1975, the structural issues that were laid bare by the recession continued eroding the economy for the next six years.

The U.S. industrial base had become accustomed to getting away with rising prices and stagnant quality. The rise of competing industrial nations such as Germany and Japan (and the resulting imbalance in trade flows that undermined the U.S. dollar’s gold-backed status) required a massive reset of America’s financial and industrial sectors.

The higher cost of energy revealed the inefficiencies of the U.S. economy, and coupled with the public demand to clean up industrial pollution, the industrial sectors were forced into a disruptive and costly reset.

The Fed’s only “solution” to any slowdown– easy money–fueled runaway inflation. The key takeaway here was: the structural problems were not financial, and as a result the usual Fed tricks of easy money failed to fix what was broken.

Instead, loose fiscal and monetary policy made the situation much worse. On top of a major reworking of fundamental issues such as energy, pollution and global competition, the policies of the Fed and Congress added runaway inflation to an already dicey situation.

The next recession in 1981-82 was devastating, as the can could no longer be kicked down the road. Inflation destroys wealth, savings, industries that rely on credit, and trust in the institutions of the central bank and state. Fed chair Paul Volcker jacked up interest rates, laying waste to auto sales and housing, and slowly but surely, inflation was tamed–at great cost.

Although political credit is generally given to President Reagan, who took office in 1981, the painful decade-long structural reworking of the U.S. economy finally began to bear fruit in the 1980s. The counterculture techies and immigrants (Andy Grove of Intel, et al.) in Silicon Valley launched the digital revolution, energy prices dropped and stabilized as the petro-dollar system was institutionalized and the economy normalized high interest rates: home buyers cheered when mortgage rates slowly declined to a low, low 10%–a big improvement over 12% mortgages.

Booms tend to generate financial crises of excessive debt and speculation, aided and abetted by regulatory lapses, and the 1980s birthed the Saving and Loan Crisis, a completely foreseeable and needless implosion of fraudulent S&Ls which sprang up like evil weeds in the loosening of basic banking statutes. (It didn’t take much to open an S&L in some states, sell a passel of $100,000 CDs, and burn the proceeds on housing speculation and high living).

The oil spike that preceded the First Gulf War was the boulder that started the landslide. The recession was brief, but it was enough to cost George Bush I the election of 1990. (People famously vote their pocketbooks.)

But the damage was relatively minimal in terms of fundamentals, and the Roaring 90s took off once President Bill Clinton declared the era of Big Government was over and fiscal restraint came back into vogue.

The explosive rise of the Internet fueled a spectacular stock market bubble in tech stocks, and as with all bubbles, the eventual popping of the dot-com bubble crushed the fortunes of anyone who bought near the top and held on to sell near the bottom. Hundreds of once high-flying companies vanished or were bought by survivors for fractions of their dot-com bubble valuations.

As usual, the Fed’s “solution” to the 2001-02 downturn was to open the credit spigots and lower interest rates, even though liquidity and interest rates weren’t what was wrong with the economy.

This monomaniacal policy inflated a monumental housing bubble in 2004-2008, and once again loosened regulations (liar loans, no-doc loans, 100% mortgages, fraudulent mortgage backed securities, etc.) plus low interest rates and abundant Fed liquidity created a bubble that was guaranteed to implode with devastating consequences.

No longer content with blowing one credit-speculative bubble at a time, central bankers coordinated their efforts in 2009-2018 and inflated the Everything Bubble. But the Everything Bubble didn’t resolve or even address the multiple structural imbalances in the U.S. and global economies; it merely papered them over with a triple-whammy credit-speculative orgy of unprecedented enormity.

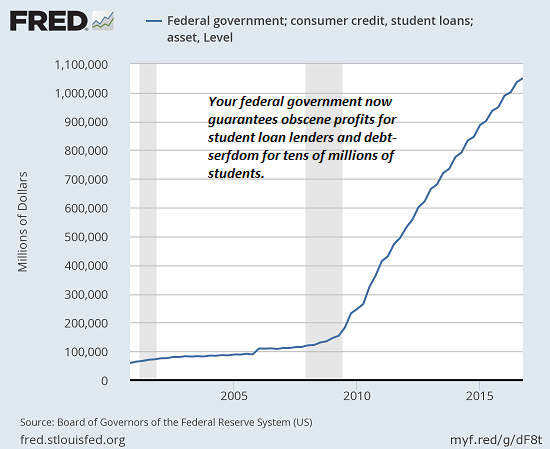

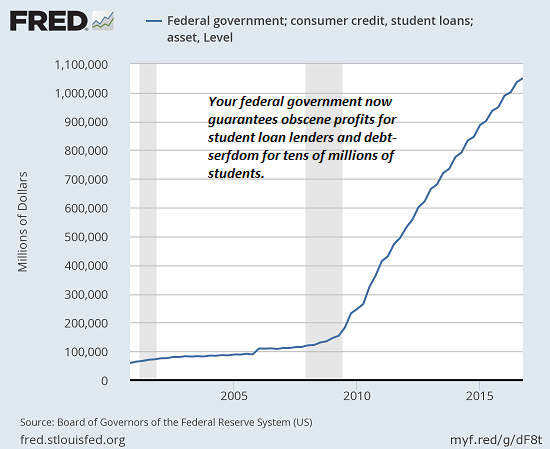

Unlike the 1970s, 80s, 90s and 2000s, wages (earned income) did not rise for the bottom 90% during the Central Bank Everything Bubble 2009-2018: it isn’t just the stock buybacks and other financier speculations that are funded by debt–a great deal of consumption that was once paid out of earnings / revenues is now paid by debt: higher education, paving of roads, auto repairs, etc.

| Rather than restructure the economy, the political and financial elites have papered over the imbalances with debt. Debt, we’re assured, is harmless; we’re going to “grow our way out of debt” by borrowing more. But borrowing more to consume more isn’t increasing productivity, and this is one reason why wages have stagnated and prices have soared in the past decade.The instabilities and imbalances of economies can be papered over with debt for a time, but debt and financialization tricks don’t actually fix what’s broken–they make the problems worse. Welcome to the recession of 2019-2021, when central bank policies are finally revealed as the’ source of half our problems rather than the solution.

We’re way overdue for a sell-everything recession, one that the Fed will only make worse by pursuing its usual policies of lowering interest rates and goosing easy money. The structural problems are now acute, and giving more free money to financiers and politically powerful corporations isn’t going to fix what’s broken in the U.S. economy. |

Federal government 2005-2015 - Click to enlarge |

My new book is The Adventures of the Consulting Philosopher: The Disappearance of Drake. For more, please visit the

book's website.

Full story here

Are you the author?

At readers' request, I've prepared a biography. I am not confident this is the right length or has the desired information; the whole project veers uncomfortably close to PR. On the other hand, who wants to read a boring bio? I am reminded of the "Peanuts" comic character Lucy, who once issued this terse biographical summary: "A man was born, he lived, he died." All undoubtedly true, but somewhat lacking in narrative.

Previous post

See more for 5.) Charles Hugh Smith

Next post

Tags:

newsletter