Eariler this week, when the San Fran Fed published a paper that suggested that the recovery would have been stronger if only the Fed had cut rates to negative, we proposed that this is nothing more than a trial balloon for the next recession/depression, one in which the Federal Reserve will seek affirmative “empirical evidence” that greenlights this unprecedented NIRPy step (in addition to QE of course).

Today, in his latest note to clients after returning from a 2 week vacation in Jamaica, SocGen’s Albert Edwards picks up on this point and cranks it up to 11 writing that “as central banks thrash around for new tools, I have long thought the next recession would trigger the adoption of helicopter money and deeply negative Fed Funds. Clients have been sceptical of the latter because of the negative impact on bank margins, but now I am more convinced than ever that we will see negative Fed Funds.”

Predictably, Edwards takes aim at the SF Fed “analysis”, writing that “just because the San Fran Fed has published this paper doesn’t mean the Washington Fed will adopt the policy in the next recession, but with this economic cycle clearly now in its final act, one can sense that a number of trial balloons are being floated on what the Fed might do in the next recession. This is just one of them.”

| More to the point, Edwards also focuses on the recent resurgence of interest in Modern-Money Theory, i.e., MMT, or government-mandated helicopter money, which is predictably a “theory” espoused by socialists everywhere most notably Bernie Sanders and his economic advisors…

… and writes that “many of the more radical Democrats in the US seem to be adopting the idea and since I expect the US budget deficit to soar to 15% of GDP in the next recession, the ideas of MMT will surely become even more popular.” Edwards is convinced that “the Fed and other central banks will be desperate enough to adopt outright monetisation (aka helicopter money, that is to say the direct central bank financing of public sector deficits) in the next recession. And as that will coincide with public sector deficits in the mid teens, we will be conducting a live MMT experiment. Welcome to a brave new world!” As validation of his (not all that controversial) view, Edwards believes that in recent weeks we have seen the Fed “take a large step away from Quantitative Easing (QE) and towards outright monetisation.”

|

Modern Money Theory, Jan 2004 - 2019 |

Naturally, Powell’s recent commentary which switched off the balance sheet unwind “autopilot” caught Edwards’ attention, and the recent trial balloons by the WSJ – and the Fed – hinting at the like likely abandonment of QT, just as it was getting started- removes any doubt in Edwards’ mind “that what we have seen since 2008 is in fact outright monetization” and asks rhetorically, “does anyone really think these bloated central bank balance sheets will ever be reduced before the next recession brings yet another tidal wave of QE?”

The answer: of course not, especially if it only took a 20% drop in stocks for the Fed to immediately reverse its “autopilot” course.

Which brings us to the topic of the next inevitable recession, in which Edwards expects our “all-knowing” central bankers will pull any and every policy lever they have to hand and that in my view includes the Fed pursuing deeply negative interest rates.”

Here the SocGen strategist concedes that the reason most clients reject this outcome is “the destructive impact negative interest rates would have on bank margins, which might exacerbate any credit crunch. Hence policy makers would therefore shy away from negative rates.”

Needless to say, Edwards himself disagrees, reasoning that unlike in the 2008 Global Financial Crisis he does not expect banks to be at the apex of the next recession, perhaps as a result of an ocean of liquidity thanks to the $1.5 trillion in excess reserves currently in the system.

I have long said that in the next recession the main toxic asset to avoid will be US corporate bonds – most especially Investment Grade. In the next recession, banks will inevitably lose money if commercial and residential property prices decline and corporate and consumer loans default – although we have been reassured that banks are better capitalised than before and that they have been vigorously stress-tested.

But more importantly due to the Volker Rule and other macro-prudent regulations, banks do not sit on mountains of corporate and mortgage paper as they did in 2007. It is pension funds, insurance companies and via ETFs, mom and pop – who bought the avalanche of US corporate bonds issued since the last GFC.

So the good news, according to the grumpy SocGen permabear, is that banks are unlikely to be a systemic risk as the next crisis drives a rapid unravelling of the global economy, like they were in 2008 (sarcastically, he then notes that he is “not known for seeing a cup half full!”).

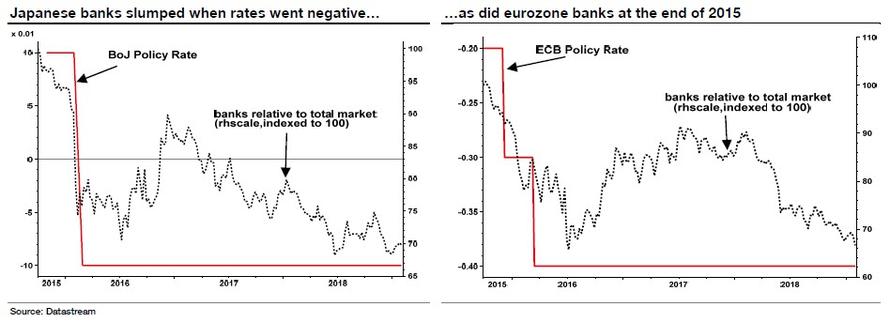

| That is why he is confident that central bankers will not care if bank profits are squeezed as interest rates are pushed deep into negative territory – including the sort of adverse market reaction towards the banking sector we saw when Japan cut interest rates from +0.1% to -0.1% in early 2016 (Japanese banks fell around 25% relative to the market as did the eurozone banks as the ECB pushed interest rates to minus 0.4%, see charts below).

Addressing just this hot topic, moments ago Dallas Fed president Robert Kaplan said that he is “skeptic about whether that’s a viable option” although he quickly added that the central bank should “not take any option off the table” even as he admitted that deploying negative interest rates in the U.S. could cause problems for the financial system. |

Japanese Banks Slumped, 2015 - 2019 |

Perhaps that’s some advice the Fed could have given the ECB, SNB and BOJ before they launched NIRP, but we digress, especially since Edwards is ultimately right, and with fears about banks off the table, banks will be driven by just one prerogative (the same one that Nomura’s Charlie McElligott hinted at earlier) – doing everything to preserve inflation, and avoid deflation, to wit:

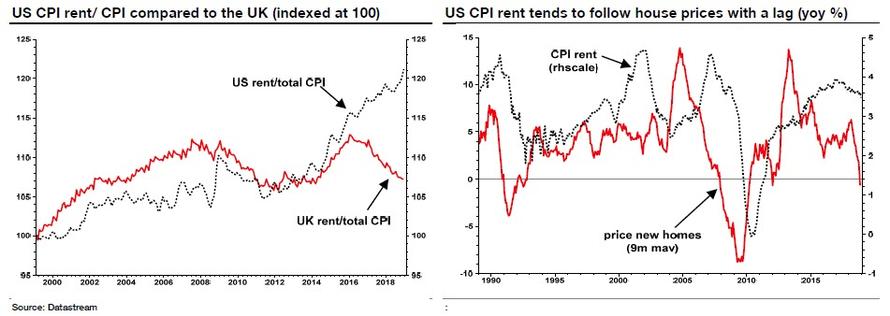

However, it is not just the eurozone that risks falling into outright deflation in the next recession: according to Edwards, the US is also vulnerable, and while core CPI and core PCE have remained relatively healthy in recent months, and roughly at the Feds 2% target, this has been mostly a function of strong rents and Owner Equivalent Rent, i.e. housing prices, which dominate the core CPI calculation. |

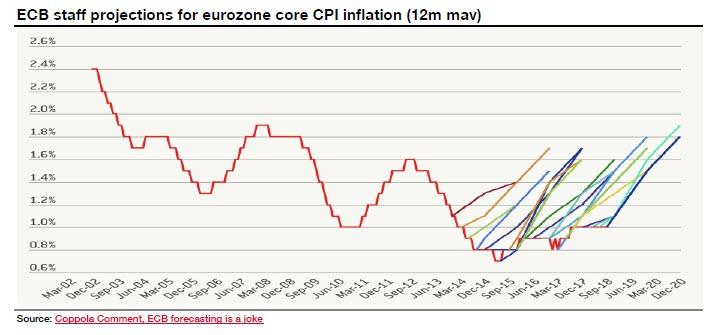

ECB Staff Projections for Eurozone Core CPI Inflation, Mar 2002 - 2019(see more posts on ECB staff projections, Eurozone Core Consumer Price Index, ) |

| However, the risk is that US rent inflation “tends to broadly follow the fortunes of the housing market overall and there is no doubt that the US housing market has begun to unravel quickly over the past six months. New home prices are now actually falling yoy (even with a heavy 9-month moving average, see right-hand chart below). The last two occasions this happened were Nov 1990 and Dec 2007 when the US economy had entered recession! Rent inflation slumped shortly afterwards. In the next recession, the reality of outright deflation will dominate investors’ fears.

Meanwhile, in addition to inflation, central banks will be keeping a close eye on the dollar (recall we noted earlier that only two factors matter for the fate of the current rally: inflation and the dollar). The reason for that, according to Edwards, is that one key policy lesson from Japan in the 1990s (and the GFC of 2008) when the economy slipped towards outright deflation is that a strong currency must be avoided at all costs as it exacerbated the deflation impulse still further. |

US Rent/Total CPI and UK Rent/Total CPI, 2000 -2018 |

Finance 101 dictates that a strong currency means import prices begin to decline and what we found in Japan, was that even where an industry was dominated by domestic Japanese producers, the marginal importer was able to undercut domestic producers and became the price setter for the whole sector. “Economists’ models could just not pick up this behavior and were unable to foresee the strong deflationary pull.”

So while Edwards predicts that the Fed does not want to rush to cut Fed Funds into negative territory, the cost of delaying will be very high if others are doing it (via a strong dollar).

The Fed will be forced to participate as avoiding deflation will be the number 1 priority – not the profitability of the banking sector. Investors should contemplate a brave new world of negative Fed Funds, negative US 10y and 30y bond yields, 15% budget deficits and helicopter money. Sounds ridiculous doesn’t it? What I said in 2006 sounded ridiculous too.

Concluding, as he often does, Edwards says that he hopes he is wrong, but fears that he will be proved right (again… eventually).

Full story here Are you the author? Previous post See more for Next postTags: ECB staff projections,Eurozone Core Consumer Price Index,newsletter