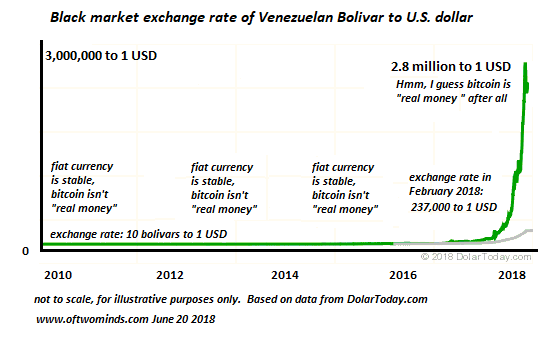

Consider how a “balanced portfolio” yielding “balanced returns” worked out for middle class retirees in Venezuela.

The fantasy that a “balanced portfolio” yielding “balanced returns” will fund a stable retirement for decades to come is widely accepted as a sure thing: inflation will stay near-zero essentially forever, assets such as stocks and bonds will continue yielding hefty income and capital gains, and all the individual or fund needs to do is maintain a “balanced portfolio” of various asset classes that yield “balanced returns,” i.e. some safe “value” lower-yield returns and some higher risk “growth” returns.

This fantasy is based on the belief that yields will exceed real inflation for decades to come. That is, if inflation is 2%, and the average yield of a “balanced portfolio” is 6%, then the inflation-adjusted return is 4% annually–not great, but enough to secure retirement income.

What few dare ask is: what happens if inflation is 7% and yields drop to 2%? Then the retirement fund loses 5% of its purchasing power every year. In a decade, the fund’s value will decline by roughly half.

Oops. Analysts such as John Hussman have been pointing out that historically, eras of outsized returns such as the past decade are followed by eras of low or even negative returns. So assuming a “balanced portfolio” of corporate and sovereign bonds, growth stocks, index funds, etc. will yield 6% to 7% like clockwork is essentially betting that: high growth will never pause or reverse.

But let’s say things really unravel, and inflation is 8% and yields are negative 2% for a few years. Retirement funds will lose 10% of their purchasing power every year. In a few years, the fund will lose half its value.

What happens if the current “everything” asset bubble pops, and inflation starts running away from policy makers? It’s worth recalling that declines on the order of 75% to 80% are common when bubbles finally pop–for example, the NASDAQ stock index post-2000.

If inflation (i.e. the currency loses purchasing power) gets out of hand due to excessive money creation to fund interest on debt, entitlements and obligations, the only cure is to raise interest rates significantly. Higher rates destroy the value of existing bonds and they strangle speculation and debt-dependent projects and spending.

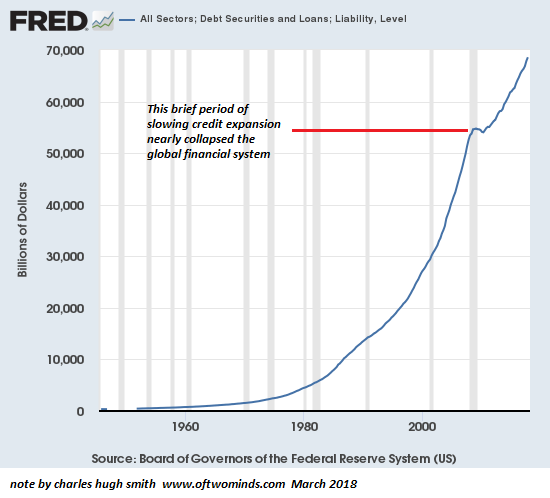

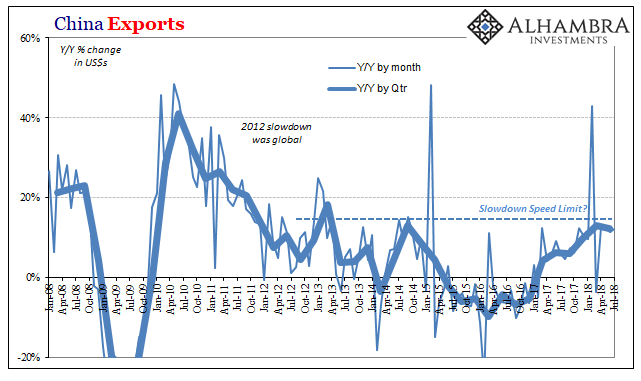

| Higher rates means corporations, governments and households must pay more each month in interest, leaving less income for spending and investment. Unfortunately, the global economy is largely dependent on rapidly expanding debt for its survival. As this chart shows, the tiny reduction in debt expansion in 2008-09 very nearly collapsed the global financial system. |

Collapsed the Global Financial System, 1960 - 2018 |

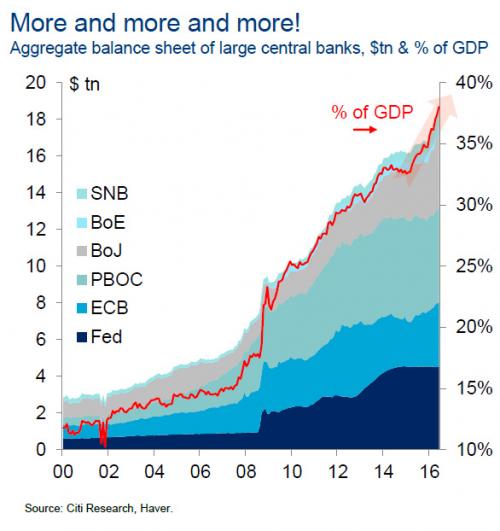

| Only the conjuring of $20 trillion out of thin air by central banks saved the day and the decade.

Counting on endless real returns of 5% or more essentially forever is embracing a fantasy. Never mind what asset mix is considered “balanced”– bubbles pop, and when the “everything” bubble pops, it means stocks, bonds and real estate will all experience significant declines, and if history is any guide catastrophic declines in some asset classes. That central banks and governments can create endless mountains of new money to fund soaring obligations without triggering a decline in purchasing power is also a fantasy. As I’ve explained in the past, it seems like central banks have created a financial perpetual motion machine: the government borrows $1 trillion to fund obligations, and the central bank “prints” $1 trillion and buys the government debt. It seems so painless and perfect–who cares if the central bank balance sheet balloons to $100 trillion? We owe it to ourselves, the government can’t go broke since it can always print more money, etc. The grim reality is printing trillions and pumping that newly issued currency into a stagnant, dysfunctional economy reduces the purchasing power of the currency, i.e. inflation. To use a health analogy, we’ve been gorging on doughnuts, pizza and beer for a decade, and since we’re still apparently disease free, we assume we can keep enjoying this diet for decades to come. The consequences of systemic sclerosis are non-linear, meaning they pile up unseen until the major organs give out and the apparently disease free individual collapses in a heap. |

Central Bank Balance Sheet, 2000 - 2016 |

| Consider how a “balanced portfolio” yielding “balanced returns” worked out for middle class retirees in Venezuela: |

Bolivar USD, 2010 - 2018 |

Tags: newslettersent