Communication from European central banks over the last few weeks has been consistent with a more cautious stance and, in some cases, is likely to lead to delays in their monetary policy normalisation plans. Each situation is different, with a loss in economic momentum, subdued underlying inflation, and political risks playing a role to varying degrees in the euro area, the UK, Switzerland and Sweden. At the same time, significant growth and FX spillovers from one region to the other suggest that there is always a limit to the degree of monetary policy divergence.

Although the next policy decisions by the ECB and SNB could be delayed, we have made no change to our policy normalisation scenario. We expect the ECB to end QE in December 2018 and to start hiking rates in September 2019 (with a risk of an earlier move in June). We predict the SNB will hike rates in December 2018 assuming the ECB has embarked on a clear normalisation path. Meanwhile, economic conditions should be met for the Riksbank to start hiking rates by the end of 2018 as well.

The biggest uncertainty we see still relates to the BoE which is likely to remain on hold in May following a string of weak economic data culminating in a large Q1 GDP miss. Although we reiterate our forecasts for protracted economic underperformance in the UK, a softer-for-longer Brexit transition would ultimately allow the BoE to go ahead with cautious and limited tightening including at least one rate hike this year, most likely in August. A second hike in December looks like a close call but, beyond that, we see further monetary tightening from the BoE possible if, and only if, the government capitulates completely and/or a full-blown political crisis leads to the UK maintaining access to the EU customs union.

ECB willing to wait until July for more clarity in the data

The ECB conveyed a balanced message of confidence and prudence at its April meeting, suggesting that they were not overly concerned about the soft patch in the economy in Q1 and willing to collect more data before they start discussing the timing and modalities of the next policy steps.

The 14 June meeting will be important as the ECB staff and the national central banks will present their updated macro projections, but the risk is that the ECB delays its next announcement to July. We think a compromise is possible, with the ECB making a conditional commitment to end asset purchases at the June meeting (ruling out another open-ended extension), but waiting until the 26 July meeting to unveil the mechanics of tapering.

The official justification would still be that QE as a deflation-fighting tool is no longer needed as the stock effect (reinvestment) and forward guidance on policy rates will contribute to maintaining an ample degree of monetary accommodation. The unofficial reason would still be that QE is finite and close to its limits unless more flexibility is introduced.

Such compromise would allow the ECB to retain some degree of flexibility and optionality. A ‘super slow taper’ could become a possibility if sentiment deteriorates further and/or inflation disappoints, effectively postponing the date of the first rate hike well into H2 2019, if not beyond.

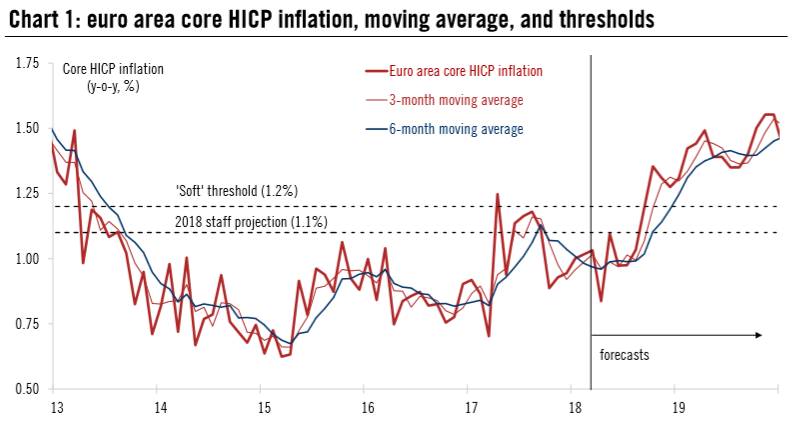

| At this stage, we expect the ECB staff projections for GDP growth to be revised marginally lower in June, in line with our own forecasts. The median projection for 2018 GDP growth would be lowered to 2.3%, from 2.4%, while revisions to the 2019-20 profile would be even smaller. With such a small revision to growth, the main focus will remain on the trajectory of core inflation. Following noisy data releases around the Easter period, we forecast euro area core HICP inflation to rebound to 1.1% y-o-y in May, which will be the last print the ECB will have going into the 14 June meeting.

Going back to Mario Draghi’s and Peter Praet’s inflation criteria, our forecasts suggest that the ECB will not have enough information ahead of the June meeting in order to reassess the potential for a “sustained adjustment” of underlying inflation. One mitigating factor would come from higher oil prices boosting inflation projections by more than 10bp while the fluctuations in the trade-weighted EUR would be broadly neutral. In the end, the timing of the next decisions is important, but the actual decisions will be much more decisive in shaping market expectations over the longer run. We expect the data to prove the ECB right eventually. We continue to expect the ECB to terminate its asset purchases in December 2018 and to start hiking rates in Q3 2019. |

Euroarea Core HICP Inflation, Moving Average, and Thresholds, 2013 - 2018 |

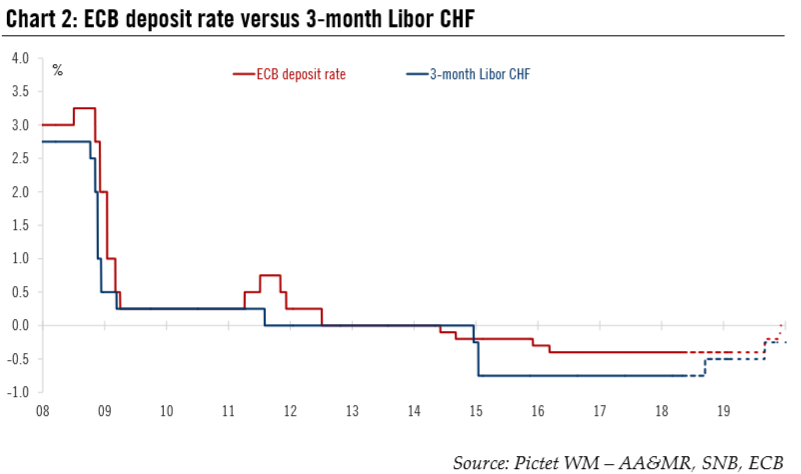

A more prudent ECB would postpone SNB’s normalisationThere are several reasons to believe that the SNB may soon start to normalise its monetary policy. First, the Swiss macroeconomic outlook has improved: Swiss growth is picking up and becoming more broad-based across a range of sectors. Headline CPI inflation has turned positive in 2017 and is gradually rising. Second, pressure on the Swiss franc has weakened. In this regard, the Swiss franc has recently reached its cheapest level against the euro since January 2015, when the SNB discontinued the minimum exchange rate against the euro. The SNB has not needed to intervene on the FX market since July last year. Third, other central banks (in particular the Fed) are gradually removing some of their own stimulus. The question is when the SNB will start to normalise its monetary policy? Our baseline scenario is a first 25bp rate hike in December 2018. But while Swiss economic conditions have improved, SNB’s monetary policy remains highly dependent on other central banks and, in particular, on the ECB. A first rate hike in December would still leave SNB’s policy rate below the ECB’s current deposit rate of -0.40%. However, a necessary condition underlying our scenario is that the ECB has clearly announced the end of its QE programme for this year and that a deposit rate hike is on the cards for 2019. If the ECB proves to be more prudent that we expect, SNB’s first rate hike could be delayed as the SNB will avoid triggering any unwarranted appreciation of the Swiss franc. |

ECB Deposit Rate versus 3-month Libor CHF, 2008 2018 |

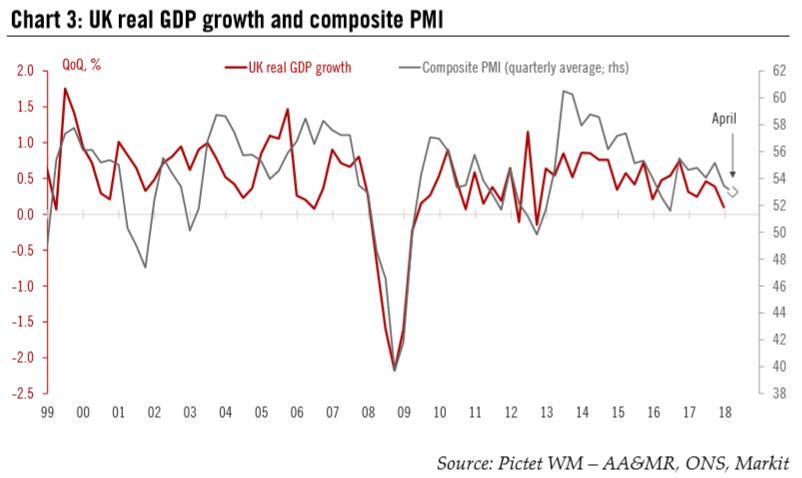

BoE to skip May crossing fingers for data to turnLast week’s UK GDP report was probably the last straw in terms of the timing of the next BoE rate hike. Real GDP rose by 0.1% q-o-q in Q1 after 0.4% in Q4, well below consensus (0.3%) and the initial BoE forecast (0.5%). While adverse weather conditions certainly weighed on construction activity, and upward revisions cannot be ruled out in the future, the ONS indicated that the net impact on GDP was “limited” as energy supply and online sales were supported at the same time. Meanwhile, the moderation in service sector growth to 0.3% q-o-q was unexpected. This extremely weak GDP report followed disappointing business surveys, industrial output and CPI inflation data, among others, as well as dovish comments from Governor Carney. This week’s manufacturing PMI failed to rebound, adding to the near term risks to activity. As a result, we now believe that the BoE will not hike in May. Based on our macro forecasts, the BoE is more likely to hike in August and then again in December, although the risk of a prolonged pause has increased. The timing and pace of BoE tightening will continue to be driven by political developments and the prospects of a softer Brexit, but also increasingly by the strength of economic data. Our scenario has long been mixed on those fronts – looking to a longer and softer Brexit transition, but also to a protracted period of economic underperformance. Our below-consensus forecasts assume GDP growth of 1.3% in 2018, and 1.2% in 2019-20. |

UK Real GDP Growth and Composite PMI, 1999 - 2018(see more posts on U.K. Gross Domestic Product, ) |

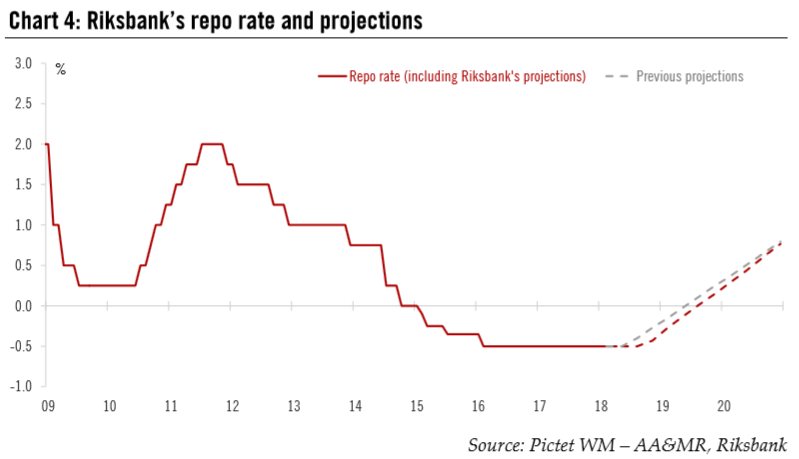

Riksbank not risking a policy mistakeIf there is one central bank in Europe whose policy stance looks most at odds with broad economic conditions, it is still the Riksbank. Asset purchases have stopped but the repo rate remains at -0.50% despite economic activity being “still strong” and inflation “close to the target for the past year”, according to the April statement. The reason why the Riksbank turned slightly more dovish in April, hinting at a rate hike “until towards the end of the year” (compared with “during the second half of this year” previously), was because core inflation came in below their forecast, at around 1.5% recently. Meanwhile, the FX pass through remains a source of considerable uncertainty, although we would expect this risk factor to fade over time as domestic forces dominate. Our broadly constructive forecasts for global and European growth this year and next look consistent with the Riksbank pulling the trigger in Q4 2018, in line with their adjusted communication, although the first rate hike could be larger in size than currently expected (+10bp). Looking into 2019, we see risks tilted towards a more hawkish reaction function as both the Riksbank’s projections and market expectations look begin in terms of the pace of tightening and the level of the terminal rate. |

Riksbank’s Repo Rate and Projections, 2009 - 2018 |

Implications for the FX market

The latest dovish shift in European central banks’ communication is in contrast with the ongoing hawkish shift at the Fed. This could provide an additional tailwind to the US dollar rebound and increases the chance that the greenback exceeds our short-term projections against European currencies.

We already flagged this risk for the EUR/USD rate (see “Euro weakness should prove temporary”; 27 April). More precisely, there is the potential for the euro to fall as low as USD1.17 in the very short term without much impact on our three-month projection of USD1.20. The same is true for the USD/CHF rate, which could rise temporally higher than our three-month projection (currently CHF1.00 per USD). In this case, we see a short-term upside potential for the USD to go as high as CHF1.03.

In the case of sterling, the likely postponement of the next BoE rate hike to August (instead of May) and the fading likelihood of an additional rate hike later in the year call for a downside revision to our sterling projections. A decline towards USD1.33 per GBP is on the cards in the next couple of months. But our central scenario of a longer and softer Brexit transition and GBP undervaluation should remain supportive of sterling in the next 12 months. We now see sterling at USD1.42 on a 12-month horizon.

Finally, we remain constructive on the Swedish krona despite its ongoing depreciation. The robust growth outlook, the convergence of inflation to the Riksbank’s target and the extreme undervaluation of the krona should eventually translate into significant appreciation, if only later than expected.

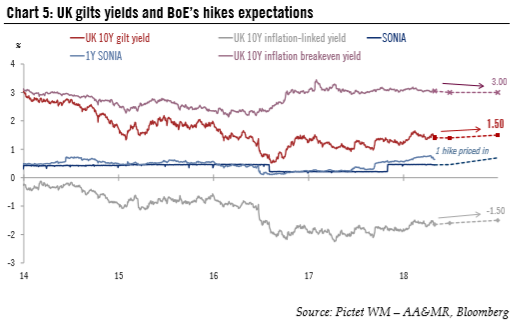

UK gilt yields cappedA weak Q1 GDP print and a more dovish BoE this year should place a cap on the 10-year UK gilt yield. Accordingly, we are adjusting our end-of-year target slightly downward from 1.7% to 1.5%, meaning that we see little upside potential over the coming months relative to our scenario (see “Core sovereign yields still heading North”; 3 October 2017). The UK economy should continue to lack momentum this year with the game changer remaining Brexit negotiations. As explained above, we expect UK 2018 GDP growth to slow down from last year, further underperforming EU growth. Adding to that, UK inflation should continue to move closer to the BoE’s 2% target from 3% during most of 2017 (due to post-Brexit sterling depreciation). According to our forecast, UK inflation (consumer price index) could decelerate further from 2.5% y-o-y in March to 1.9% at the end of the year, reducing upward pressure on the 10-year inflation breakeven yield (see Chart 5). Historically, breakeven yields have been high in the UK, and we expect them to remain stable at around 3% rather than revert to 2%. Weak economic growth and decelerating inflation should make the BoE more dovish and lead it to postpone its next rate hike to August. Looking at the sterling overnight index average (SONIA) futures market, on 1 May, investors were pricing less than one further 25bp rate hike over the coming year down from more than one at the beginning of April). As the macroeconomic outlook is making a second hike this year less likely (unless negotiations head clearly in the direction of a soft Brexit), we estimate than the 10-year inflation-linked gilt yield has only little upside potential. In fact, UK inflation-linked yields are very dependent on monetary policy and we would need to see a decisive rate-hiking cycle by the BoE before they move back into positive territory. In this case, we would probably have to raise our 10-year gilts yield target. |

UK Gilts Yields and BoE’s Hikes Expectations, 2014 - 2018 |

Full story here Are you the author? Previous post See more for Next post

Tags: Macroview,newslettersent,U.K. Gross Domestic Product